The social history of the Internet is embodied by bloggers, influencers and all those extremely online personalities who have shaped – some say hijacked – the Internet.

Two new documentary films and a national bestselling book make the case very clearly. They present fascinating looks at the rise of online influencers and the creator economy, while also presenting poignant, sometimes painful, profiles of its founders, failures, and trailblazers.

For better or worse, these accounts spotlight how online influencers rattled the media gatekeepers, waved off accepted social norms, disrupted the world of pop culture and created whole new sectors of the economy, both on and offline.

And may have left us right where we started.

A penetrating look at the world of social media is presented in the new National Film Board of Canada documentary Anything for Fame.

One penetrating look at the world of social media is presented in the new National Film Board of Canada documentary Anything for Fame, in which director Tyler Funk profiles the ambitious—and sometimes reckless—new breed of online content creators.

Dozens of online influencers appear in the film, including several Canadians, as does their hunger for notoriety in the unforgiving attention economy that’s been created online. The doc shows how, in the world of social media, only a few creators really strike it rich. Many find themselves facing technical pitfalls and moral dilemmas as they inhabit an online world where likes and views are the stuff of dreams.

These influencers will do “anything for fame”, and as a result, the filmmakers must warn us that “Viewer discretion is advised.” But the documentary still manages to treat the online celebrity with empathy and the online phenomenon with insight.

In Extremely Online (her debut book is already a bestseller), Washington Post reporter Taylor Lorenz delivers a comprehensive social history of the Internet. Photograph © Brian Treitler.

Washington Post reporter Taylor Lorenz wields her own influence and insight, with her well-researched and behind-the-scenes book that recounts the remarkable stories of seemingly ordinary, everyday people who managed to – sometimes – build their own media empires with sheer talent, algorithmic luck or a bit of both.

In Extremely Online (her debut book is already a bestseller), Lorenz delivers a comprehensive social history of the Internet, the online influencers and the creators who have managed to upend our ideas about of content and community, buying and selling.

From the moms who started blogging and found they could “monetize their personal brand” to the bored kids who posted selfie videos and reinvented fame as we know it, to the “pro-creators” on TikTok who are making for themselves an attractive alternative to the hamster wheel of the job market, Lorenz makes the trajectory clear.

It’s been said Extremely Online tell a sociological story, not a psychological one, but Lorenz still explores the impacts of what ‘we’ have done to the Internet, and in turn what the Internet has done to ‘us’.

Beginning with the Blogging Revolution, Lorenz describes in some detail how the “web log” gave early Internet users a way to share their thoughts and favourite links with “the world” (keep in mind that in the early ’90s, perhaps one half of one per cent of the world’s population was online; today, it is about 66 per cent).

Early blogging programs like Blogspot and WordPress (a tool in use here today) emerged which, while mostly text-only, could be used to set up a site in just minutes.

Lorenz reminds us just how radical this concept was – anyone with Internet access could be a publisher, and in a click, media consumers became media producers. Blogging platforms like MySpace and Vine (anyone remember Bolt?) helped aggregate and consolidate the growing power of the individual blogger. The gates were being rattled.

Then, in the early 2000s, tools emerged to let bloggers sell display ads on their sites: they could use the same ad-driven business model as the mainstream outlets, but with vastly lower overhead and a more direct connection to the audience. The gates were coming down.

By the end of the 2000s, Lorenz describes, after mainstream media outlets and established publications clued in to what was happening, a wave of mergers, acquisitions, buy-outs, squeeze-outs, hiring raids, lawsuits and other consolidations left us with a mashed-up social media space in which the upstarts soon looked like the incumbents: “[L]ooking like the parasite and host had merged,” Lorenz writes.

(According to a recent U.S. poll, 14 per cent of 16 to 54-year-olds (some 27 million people) say they are working as influencers in the national economy. The creator industry itself could be worth some $480 million (USD) by 2027, but traffic and wealth are concentrated among a very few creators with less than 10 per cent of full-timers earning a decent wage and the vast majority making less than $2,000 a year.)

As she develops the story, Lorenz shines the spotlight on some of the influencer pioneers such as Heather Armstrong and Julia Allison.

Armstrong was the ‘Queen of the Mommie Bloggers’ and one of the first to write openly and honestly about parenting anxieties and romantic relationships, as well as her own personal struggles, encounters with postpartum depression and alcoholism.

Armstrong enjoyed financial success with her successful Dooce website, but sadly, she took her own life earlier this year.

Some 20 years ago, multi-platform content creator Julia Allison came to dominate the online world with her own sense of style and substance. In many ways, she was ahead of her time: rather than a celebrity, people saw her as a narcissist. The term social influencer did not exist (nor did multi-platform content creator) and Allison was terribly mistreated (an early victim of ‘trolling’) by a rude, misunderstanding audience and a threatened media establishment, both of which are still uncomfortably present in today’s online world.

(If you want to learn more about the remarkable story of this early online influencer, there is an exclusive excerpt of Lorenz’s book online from Rolling Stone that is well worth checking out.)

(If you want to learn more about the remarkable story of this early online influencer, there is an exclusive excerpt of Lorenz’s book online from Rolling Stone that is well worth checking out.)

Lorenz’s work has long been accessible on many platforms, starting with her days as a tech reporter for The New York Times business section, The Atlantic, and The Daily Beast. As mentioned, she’s now the technology columnist for The Washington Post’s business section covering online culture.

As such, she’s surely an influencer herself: named to Fortune’s 40 Under 40 list of leaders in Media and Entertainment, she’s also one of Adweek’s Young Influentials Who Are Shaping Media, Marketing and Tech. Last year, Town & Country magazine named her to its New Creative Vanguards list of next generation creatives. Of course, you can follow her online @TaylorLorenz on Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube.

Describing many of the characters in the book in terms of successful marketing deals and hordes of social media followers makes a certain sense in this context. There is, of course, a darker side to our digital existence, one that’s uncovered in a disturbing way in a documentary that takes on social media influencing and deep fake technology.

Sophie Compton and Reuben Hamlyn’s documentary Another Body explores deepfake technology and the online

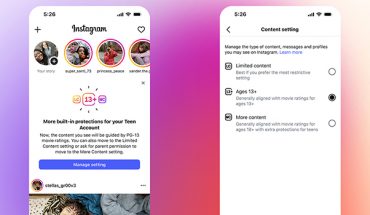

Another Body follows a college student’s search for answers and justice after she discovers deepfake pornography of herself circulating online.

psychological – and sometimes real-world physical – abuse it can bring forth. The 2023 doc follows a college student’s search for answers and justice after she discovers deepfake pornography of herself circulating online.

The film reminds us how technology and pornography have been intimately linked over the years. Portable personal video cameras. Subscriptions to cable TV channels. VR. Now AI and deep fakes. Pornography has proven time and again to be a driver of technical innovation, for better or worse. Worse, according to Another Body: the number of deepfake videos that exist on the Internet doubles every six months, and the film cites researchers who say there will be 5.2 million deepfakes in 2024; 90 per cent of them will be non-consensual porn files of women.

As the filmmakers point out in their press package: “[T]hese videos are fake, but their impacts are all too real.”

It’s a sad and somewhat infuriating reminder that, from toxic sexism and hyper-masculinity to boys doing silly stunts and girls promoting their sexuality, the online world – despite the accessible communication channels and creative opportunities it presents – is not so different after all from the mainstream media in the ways women are treated and men depicted.

-30-