Scientific research, neurological evidence, and wearable technology developed here in Canada are, well, painting a picture of how just how much we’re stimulated by art.

Research into the many impacts that exposure to the creative arts can have on the human brain has long made the connection between simply looking at art and feeling better, even living longer.

Art – viewing and making – has a measurable impact on brain wave patterns, nervous system activity, even the levels of positive neurochemicals our bodies release, like serotonin and dopamine. Scientific evidence shows that connecting with art not only enhances our brain function, but positively affects our emotional state. Existing research and new sensing capabilities are opening up “the neuroscience of happiness” and the field of “neuroaesthetics” to document how we respond to the arts.

Gallery-goers wear sensor-laden headsets that captures human brain activity as electroencephalogram (EEG) signals; a special program converts them into artistic visual imagery.

Now, there’s a new integrated technology platform that brings it all together, letting visitors see the electronic signals zipping around in their brain when looking at art and converting them into colourful 3-D imagery that’s displayed in real-time on large TVs nearby.

Gallery-goers wear a sensor-laden headset that captures human brain activity as electroencephalogram (EEG) signals; wearable Muse devices developed by Toronto-tech company InteraXon are used; the advanced technology and multiple sensors in these headsets can track not only brain activity, but heart rate, respiration, body motion and more.

Electronic signals zipping around the human brain when looking at art (Van Gogh’s self-portrait, hanging in the background, will certainly do) are converted into colourful 3-D imagery displayed on large TVs nearby.

For the ‘Brain and Art’ project currently touring art galleries and museums in the U.K., EEG signals are captured and then put through a unique visualization program created by special effects company The Mill in collaboration with interactive artist Seph Li.

EEGs have been seen before as 2-D images but transforming them into three-dimensional visualizations takes the technology a step further and colourfully shows people the impact art can have on their brain as it happens.

Will MacNeil, The Mill’s Creative Director, described how EEG waves are transformed into colourful moving ribbons and that when the wearer is more alert or visually attentive, the ribbons become wider. When someone is trying to make sense of something confusing, the ribbons start to spiral and weave on screen. If something is shown that the person recognizes, bright highlights appear.

Art Fund, the UK’s national charity for art, says the technology demonstrates the “clear and immediate impact” art has on the human brain.

Art Fund, the UK’s national charity for art and funder of the project, says the technology demonstrates the “clear and immediate impact” art has on the human brain, adding that the visualizations of the viewers’ brainwaves as they look at different paintings and objects in the gallery are themselves a kind of art. Of course, the agency hopes to inspire more people to visit museums and galleries as a result of the new revelations.

Neuroaesthetics is a term first coined in 1999, when researchers Semir Zeki and Tomohiro Ishizu got volunteers to look at art and listen to music while lying in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner.

The researchers saw an area at the front of the brain called the medial orbito-frontal cortex (mOFC) consistently ‘lighting up’ whenever a person looked at or listened to something they considered beautiful. (Ugliness gets a reaction too, but from another part of the brain.)

And the University of Toronto’s Oshin Vartanian has been exploring the different ways people observe and appreciate art on a neurological level for many years.

Co-Editor of Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts and an expert on the neuroscience of aesthetics and creativity, in his writings and gallery talks Vartanian explains how “art impacts brain function, thinking and emotions” and how “our brain influences our perceptions of beauty, our preferences in art and the meaning and relevance we ascribe to it.”

Vartanian has observed how the brain responds differently to art created by great masters versus computer-generated art; how the brain responds to authenticated art versus forgeries; and how we respond to art seen in and outside museum settings.

Further research in a 2021 study Art Making Promotes Mental Health: A Solution for Schools That Time Forgot by Dr. Brittany Martin at the University of Calgary underscored the relationship between the arts and mental health, as established in the field of art therapy, and how seeing and making art can boost the capacity for managing our mental and emotional well-being. She had administered a series of basic art exercises for a sample group of school-based mental health professionals who worked in sites across the province as part of Alberta Health Services’ Mental Health Capacity Building in Schools Initiative.

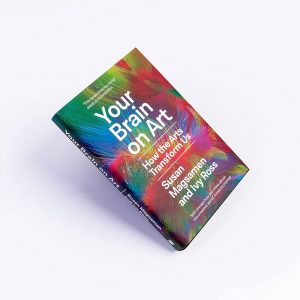

Then, in their 2023 book, Your Brain on Art: How the Arts Transform Us, co-authors Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross explore how the emerging field of neuro aesthetics is proving that art and artmaking impact the brain, alter brain wave activity, and contribute to a calmer, even healthier state of being.

aesthetics is proving that art and artmaking impact the brain, alter brain wave activity, and contribute to a calmer, even healthier state of being.

Magsamen is the founder and executive director of the International Arts + Mind Lab at Johns Hopkins Medicine’s Pedersen Brain Science Institute; Ivy Ross, vice president of design for hardware products at Google.

Their book shows with research studies and case histories how the arts generate chemical and physical responses that help us feel better. In the visual arts, familiar, repeating patterns, and colours like blue and green can reduce anxiety; in music and dance, the sound, vibration, and rhythm can trigger the release of dopamine and oxytocin, which counteract depression and anxiety.

Of course, technology is being used not just to show the arts have such powerful effects on our brains, but also our states of mind, even our spiritual aspirations.

In his work, researcher and neurotheologian Andrew Newberg takes brain scans of people who are praying, or meditating or engaging in other religious or ritualistic activities. Perhaps not surprisingly, he’s measuring some of the same responses with the brain on Buddha as with the brain on art.

# # #

The brain is art: Painted brains, such as now on display in Toronto’s Nathan Phillips Square, are part of The Brain Project, from the Baycrest Foundation, to raise awareness about brain health.

-30-