Creating a new river may not be the first thing you mention when talking about using drones.

But as work nears completion on the big Port Lands project in Toronto − it’s one of the largest projects of its kind in North America − the Digital Project Delivery team from construction services giant EllisDon continues to gather important information about the site and the final stages of this major land revitalization and infrastructure improvement project by flying drones around.

Parts of Toronto are still in recovery mode following recent widespread flooding in the city, and planning for a more resilient urban infrastructure in the face of extreme weather events is certainly underway in many other urban centres.

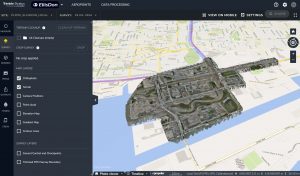

The overall Port Lands project site terrain is shown in an on-screen ‘ortho-view’, which can correct for angled camera views. Image credit: EllisDon.

In many ways a public safety initiative, the Port Lands Flood Protection (PLFP) and Enabling Infrastructure project is designed to protect Toronto’s southeastern downtown waterfront from severe flooding, in part by giving the Don River a new and more open route to the lake. Long constricted by urban and industrial development, the river’s water often had nowhere to go.

Giving the Don an outlet is a crucial part of the project; so, too, transforming big swaths of old industrial area into new public parks, adding open green spaces, and putting in place an updated infrastructure to support further residential and recreational use of the area.

Using powerful drone hardware and software systems, the EllisDon team has captured multiple high-resolution image sequences of the site over time. Special software enables what are known as ‘orthophotos’, which are geometrically corrected images showing true perspective and ground feature positions across an entire image, adjusted for camera angle and other variables. The team can also manipulate drone imagery into digital 3-D models that support precise design and construction activity throughout the multi-year project.

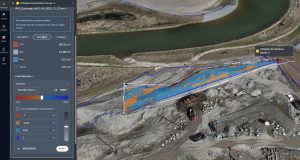

Using special software, drone views of the construction site can be compared over time. Image credit: EllisDon.

Gathering data intelligence and then visualizing it across different media platforms is an important new development in construction, and it’s a big part of growing industry disciplines called BIM (building information modelling) and VDC (virtual design and construction).

Drones are but one way to do it, as the Port Lands project reveals.

The $1.25-billion project is funded by all three levels of government; construction began in 2018 and the new parks and river will be fully open next year.

By now, drones are a familiar and important piece of the jobsite.

Patrick Lalonde, Senior Director, Digital Project Delivery from EllisDon.

They’ve been gathering precise, photo-realistic details across the entire active site area, usually in a matter of hours and often on a daily basis. Potentially millions of actionable data points are gathered. Repeatable image and data collection flights are pre-programmed and precisely mapped using markers on the ground, GPS in the sky, and sophisticated software back in the office that makes accurate views and detailed analytics available, on demand, to site managers, contractors and stakeholders, often within hours of the flight.

Real-time drone fly-throughs, multi-dimensional computer models, as well as virtual and augmented reality (VR and AR) views of construction progress and activity on the site are familiar territory for Patrick Lalonde, Senior Director, Digital Project Delivery at EllisDon.

“Over the years, technology has evolved to support the construction project in many ways, incorporating all sorts of digital media,” he explains. “We’re now using drones and other high-res cameras for reality capture, we’re incorporating LiDAR imagery, we’re including data gathered from remote sensors on-site, any number of sources.”

They all tie back to one key entity on any construction project: now not a paper blueprint, but the digitized model. It acts as a complete digital duplicate for assets and activities on the site as well as a document of the construction history for future reference.

Cross-section elevation displays are used to generate and evaluate comparison views of the construction site. Image credit: EllisDon.

In fact, the model moves beyond three physical dimensions to include activity scheduling data (a 4-D model) and costing (a 5-D model).

In compatible AR programs, up-to-date data points can be superimposed over site visuals and viewed using a headset connected to a laptop while on the construction site itself.

Having the necessary equipment and expertise to create such data visualized content in-house, Lalonde underscores the value of “having a digital model of what the project is supposed to look like at the end alongside a digital model of what it is like today so we can compare situations, end states, and current conditions very effectively.”

High-resolution images captured by drones for construction documentation purposes can clearly show all terrain symmetry, objects and/or activity on a site, and hundreds of detailed images are taken in a series. Drone models like DJI’s Mavic 3 Enterprise, for example, have cameras on board with CMOS image sensors and effective 48-megapixel resolution for images up to 8000 x 6000; there’s also 4K video capture and transmission capabilities on these models, up to 3840 x 2160 at 30 frames per second.

Photo, video and LiDAR drone flights are programmed along pre-planned paths using specific application software, with coverage set as a grid pattern across specific areas of the huge, multi-acre site.

Drones and digital media assets of many kinds can play a big role on a modern construction site. Photo credit: EllisDon.

“Pre-programming the flight path is very important,” Lalonde describes. “For consistency in the coverage, we must fly the same trajectory every time. Creating depth perception in the image sequence means the software needs to see the same surface features from different angles. And we need a certain amount of image overlap and triangulation to ‘stitch’ the images together in software.”

The altitude of a drone and flight path height are directly connected to the resolution of camera, he adds, as well as the overlap that must be achieved. There’s a “sweet spot” he’s always looking for that gets the best of image resolution, required elevation, and the visual detail needed to meet the requirements at hand.

Of course, wind and weather conditions can impact planned drone flights, and there are several aviation and navigation requirements for safe flight applicable at any given time. Drone pilots in Toronto (and all major Canadian cities) must follow Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARS, and Lalonde’s team must coordinate drone flights and clearance with the control tower at nearby Billy Bishop Airport, as well as officials at Transport and Nav Canada.

Whether using a surveyor’s tripod stand or HD camera-equipped drones, data gathering is all-important on today’s construction site. Photo credit: Waterfront Toronto / Vid Ingelevics / Ryan Walker.

Storing the as-yet undetermined total number of terabytes of drone footage and construction data his team will have accumulated does not concern Lalonde.

He says wrangling all that data will have real benefit down the road, whether the value comes in Port Lands project post-mortems, new project development and design, or sharing the experience and insights gained on this major construction project.

Over the years, Mississauga, ON-based EllisDon has advanced construction building practices, developed patent-pending materials, and incorporated new digital techniques and technologies into its many activities, from high-rise construction to riverbed creation.

For the Digital Project Delivery team, drones and data are like hammers and nails.

-30-