The Aga Khan Museum in Toronto is celebrating ten years of operation with new art exhibitions and digital experiences it hopes will engage even wider audiences across a global stage.

The Museum will launch a brand-new streaming service early in 2025, called Connected. It will offer new ways to explore the art and experience the programming, and a yearly subscription will unlock even more content, including live events recorded on-site.

The new streaming service will be part of an enhanced and expanded website, featuring newly digitized artwork and historical manuscripts, for example. A special new Learn feature is also planned, which will support on-going educational and curatorial activities presented by the Museum.

“Over the past 10 years, the Aga Khan Museum has steadily grown its impact as a beacon of cultural exchange, fostering understanding and appreciation of the rich, diverse tapestry of Muslim cultures and their interconnectedness with the world,” explained Dr. Ulrike Al-Khamis, Director and CEO of the Aga Khan Museum.

That growth includes several recent exhibitions which highlight many artistic – and scientific – developments over the years, as well as the increasing use of digital platforms, such as the recently-updated Aga Khan Museum app (more on that below).

In addition to a retrospective exhibit that is now reliving some of the Museum’s ten-year history, another current exhibition uses art, science, and light to explore how our perceptions, emotions, and understanding of the world came to be.

Light: Visionary Perspectives appreciatively uses art to explore light as both a scientific concept and a visual medium, while also linking past knowledge with current events.

My history teacher would love it.

‘Everytime you check in, don’t forget – there’s an Uzbek scholar from the eighth century in your smartphone!’

The teacher was making a point about the development of Western culture as much as he was providing specs about our digital devices.

But his point – and one also being illustrated at the Aga Khan Museum – was that while much of what our culture and civilization has accomplished deserves merit, we should appreciate that much is rooted in the accomplishments of others, often made centuries ago.

Meet al-Khwarizmi.

Whether from present-day Uzbekistan or perhaps Iraq, the work of this brilliant young Islamic scholar, known as the father of algebra, had a profound impact on the advancement of mathematics in Europe following the dark ages – and much of our computerized world later on.

Today, he could even be called the father of the smartphone.

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (c. 780-850 A.D.), was a mathematician, astronomer, geographer and historian. A Latinized version of his name gives us the word “algorithm”, and there’s not much we can do without them today.

And in many obvious and some subtle ways, we cannot do without light, either. Physically, spiritually, technologically, we should all ‘give thanks for the light’*.

Art shows us why.

The installations on display are often hypnotizing to look at, but they also offer moments of serious and sober self-reflection. Luckily, there are also kid-friendly activities coordinated with the Ontario school curriculum that shows some fun ways to learn about the science of light.

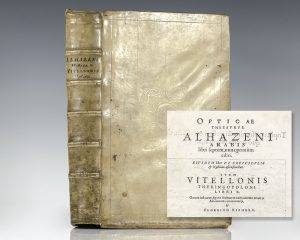

Opticae Thesaurus is a Latin translation of Kitab Al-Manazir (Book of Optics) by 10th-century Muslim scholar and mathematician Ibn al-Haytham, known as the Father of Modern Optics. It’s the foundation for our scientific understanding of optics and the structure of the eye. The printed book highlights the transmission of knowledge from antiquity to the Islamic world and, through Latin translations, to the Western world.

In shining a light on Muslim scholars, the exhibition spotlights the Opticae Thesaurus, a 16th-century Latin translation of an 10th-century text on optics which again shares ancient wisdom and insight, this time into how light interacts with our eyes, how we interact with light.

Using an array of electrical components, LED lights, photosensitive materials, video loops and more, the exhibition features installations by a wide-ranging group of prominent international and Canadian artists, including Anila Quayyum Agha, Tannis Nielsen, Olafur Eliasson, Kimsooja, and Anish Kapoor, among others.

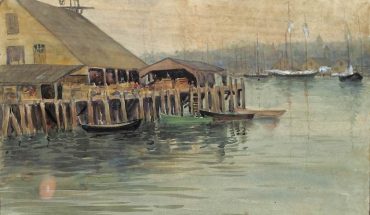

As well as the art, the exhibition explores how light interacts with the Museum itself, and its noted architecture and physical design.

From its daily playful interaction across the surrounding pools and the solid granite exterior of the building to the specific patterned rainbow-like shadows cast inside its courtyard, light always has an impact on Museum visitors, be they inside or out.

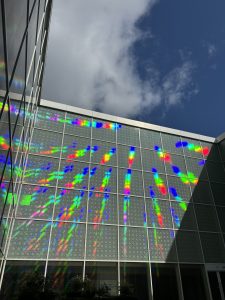

Kimsooja, To Breathe – Aga Khan Museum, Toronto, Canada, 2024. Site specific installation consisting of diffraction grating film and mirror floor panels, size variable. Photo credit Toni Hafkenscheid.

In that vein, artist Kimsooja layered the Courtyard’s surrounding glass with a special film that “makes the invisible visible” for visitors even before entering the exhibition itself.

Ambient daylight is turned into a kaleidoscopic rainbow and, as time and weather change, various colours float through the space. Like white light shone through a prism, To Breathe reminds the viewer that the much greater whole is made up of many individual elements.

But once entering the formal exhibition, Museum-goers are confronted with the collective power of creation.

Projectors show light imagery moving across, up, and down a large, darkened space. Like shooting stars and masses of energized plasma, the light projections energetically move across the walls, up to the ceiling and down into a seemingly bottomless pit (created by a mirror-like reflective floor covering).

These projected light sources are accompanied by the narration of an Anishinaabe creation story, presenting an Indigenous perspective of the Big Bang and what’s believed to be the beginning of the universe.

Tannis Nielsen, mazinibii’igan / a creation, 2020. Digital video, artist’s own footage and derivative. Story and narration by Marie Gaudet. Courtesy of Tannis Nielsen. Photography credit: Aly Manji.

Created by Tannis Nielsen, an Anishinaabe-Red River Métis multidisciplinary artist, the looped digital video installation actually allows for multiple beginnings – and middles and ends. Indigenous science, creation myths, quantum physics, electromagnetic energies, lights and sounds are all combined in her piece, called mazinibii’igan / a creation.

Everywhere there is light, there is shadow. Everywhere there is darkness, there can be light. All light is an amalgam of many differences.

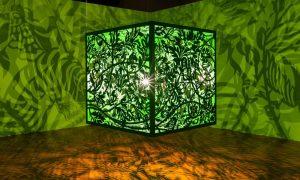

These compelling, unifying, liberating themes may best be shown in the exhibited work of Anila Quayyum Agha, called A Thousand Silent Moments (Rain Forest).

In this, her first showing of work in Canada, she fills the room with light and shadow, emanating from a lighted, intricately carved box. Multiple LED lights cast multiple shadows through the carved box onto the surrounding walls. From this seeming chaos of light and dark, one begins to see that familiar shapes can emerge, that constants do remain, that specific images can be discerned amid this forest of shadow and light.

There are many other fascinating and beautiful artworks in the exhibition, exploring the concept of light through digital media, photography, fabric and textiles, stained glass, even moonlight.

The last artwork on display as a visitor walks through the exhibit space proper is in its own space, one at least partially defined by several tall LED-and-glass modules architected as the two opposite corners of a room.

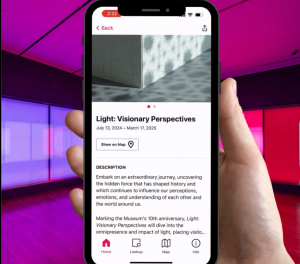

The Light: Visionary Perspectives exhibition is featured in the newly-updated Bloomberg Connects art app, which includes the Aga Khan Museum among dozens of the world’s leading galleries and museums.

Two Corners, by American artist Philip K. Smith III, encloses an open space and then bathes it in a “choreography of colour”: the LED panels are programmed to gradually change the hue, saturation, and brightness or intensity of the coloured light they emit. Sometimes, the light is dimmed so much as turn to the glass LED panels into mirror-like surfaces, reflecting the opposite corner as well as the people in the room, all seemingly afloat in a wash of ever-changing colour (the entire experience is well over an hour).

But in about five minutes or so, the artist himself describes and explains Two Corners, as part of the newly-updated Bloomberg Connects art app, in which the Aga Khan Museum is but one of dozens of the world’s leading galleries and museums to participate (and it was the first Canadian museum to do so). Also featured in the free app are other images, artists’ statements, curatorial perspectives and more from the Light exhibition itself, the Aga Khan Museum in general, and the many other museums and galleries featured.

Marking the Aga Khan Museum’s 10th anniversary, the Light: Visionary Perspectives exhibition is co-curated by the Museum’s Associate Curator Bita Pourvash and Special Projects Curator Marianne Fenton.

Anila Quayyum Agha, A Thousand Silent Moments (Rain Forest), 2024. Lacquered steel and LED bulbs. Commissioned by the Aga Khan Museum. Photography Credit: Aly Manji.

This special show not only explores various physical properties and symbolic elements of light, but it also underscores how we all can be inspired by what light allows us to perceive – through our eyes, our hearts, our minds.

As Dr. Al-Khamis said when the exhibition first opened at the Aga Khan Museum: “Light, in all of its manifestations, is a powerful metaphor for the positive change that we are aiming to drive in everything we do at our Museum. This exhibition reminds us of light’s power over darkness and the crucial role of creativity in showing us new, hopeful horizons. Over the past decade, we have consistently looked to the arts to provide light and enlightenment, with the aim to contribute to more inclusive, pluralistic communities.”

*In that sense, in many other ways, we should ‘give thanks for the light’. That idea is embodied in an old Indigenous prayer, attributed to Shawnee chief Tecumseh, who died fighting in what’s now called the War of 1812:

“When you rise in the morning,

Give thanks for the light…”

And all it lets you do.

-30-

This article has been updated since its original posting. More articles on Aga Khan Museum