Recent technological advances in AI have been coupled with Indigenous cultural wisdom and community experience to bring a language spoken by nearly 40,000 Inuit in Canada to the popular Google Translate platform.

Inuktut is a broad term encompassing different languages and dialects spoken by Inuit across northern Canada – as well as Greenland and Alaska.

Inuktut, a broad term encompassing different languages and dialects spoken by Inuit across Canada’s North – as well as Greenland and Alaska – has been added to the free language translation platform, which translates text, documents, and websites from one language into another.

A combination of machine learning and human input were needed to help the popular Google Translate learn Inuktut, and it became the first First Nation, Métis, or Inuit language used in Canada on the platform.

(There are many other langauge tools and platforms, of course: Microsoft’s Bing, for example, offers Inuktitut translations, and a small Canadian company, Seeing Red Media, has announced plans to develop leading-edge Indigenous language and speech tools.)

For its part, Google worked with many Inuktut speakers, Inuit elders, community leaders and members, and other cultural organizations during the program’s consultation and development phases to make its cloud-based translation service accurate and relevant. Giant collections of Inuktut words (again, it’s a broad term that includes dialectic or regional variations such as Inuktitut, Inuinnaqtun, and Inuvialuktun) were assembled from multiple sources to make the large language models used to train AI systems and platforms.

Dialect-level translations are not the only unique translation challenge the platform faces: in Inuktitut, a single word can often be used to express an entire phrase or sentence from English; they’re called “cluster words” and their appropriate use can convey richer meanings than core translation.

(The fact that some commentators have inaccurately said that the Inuit have some 50 separate terms for snow may reflect the power of cluster words; in fact, there’s really only six or so core terms for the white stuff.)

There are, interestingly enough, many terms for another equally important concept, that of family members and next-of-kin: for example, Google Translate knows that different terms are used by an Inuit male and an Inuit female when they refer to a brother, and men use different terms if the brother is older or younger than they are. And there’s a different term for a family with just one child, be they an only son or an only daughter.

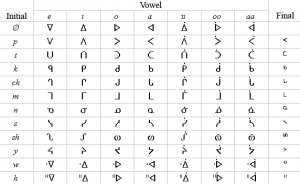

And it’s not just translation accuracy but written representation that’s also crucial to making sure the platform is true to the Inuktut language: it uses two different writing systems.

One writing system, known as qaliujaaqpait, uses the familiar Roman alphabet to represent specific spoken sounds across various dialects. The other, called qaniujaaqpait, uses syllabics – graphic-like symbols or glyphs – that represent consonant-vowel pairings.

The syllabary for Ojibwe consists of just nine symbols, each of which could be written in four different orientations to indicate different vowels. It was first developed in 1830 by James Evans, a Wesleyan missionary, and later adapted for other First Nations.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the Ottawa-based national organization representing some 70,000 Inuit here in Canada, partnered with Google to help make sure the service translated Inuktut words and phrases accurately, and that translation were available in either style of written representation.

Many years ago, ITK recommended that Roman orthography be used as the standard writing system in early schooling and education efforts to facilitate language learning, with syllabics being introduced in later grades. In February 2016, translators and interpreters attending a major conference in Iqaluit, Nunavut, voted in favour of such a reform and it was fully approved by 2019.

ITK developed its own data set of common characters that can be used to convey any dialect of Inuktut in written communication among the different Inuit regions, and now its partnership with Google opens the linguistic door even wider. Google and ITK developed a tool based on the Inuktut Qaliujaaqpait Converter to ensure that services could be offered in both writing systems.

ITK has posted on social media about the new tool it hopes will help promote increased knowledge of Inuktut and Inuit.

“As the national representational organization for Inuit in Canada, we strive to revitalize, protect and promote Inuktut,” Natan Obed, ITK President, explained. “We welcome Google’s work to include Inuktut in its roster of languages on Google Translate. The addition of Inuktut on such a widely used platform empowers Inuit to interact more fully in the digital world.”

(To learn more about the Inuktut language and the work that ITK does to to preserve it, visit the Inuktut Qaliujaaqpait webpage.)

Google says ITK’s collaboration and input about translating as well as writing the language accurately was indispensable, but it acknowledges that “translation models are imperfect and this tool will still make many mistakes.”

A screen grab from Google Translate and its new Inuktut language translation service.

As more feedback is gathered, and as machine learning technology advances, Google says it will continue working with linguists, first-language Inuktut speakers, and Inuit leaders to improve the translation quality and expand the capability even further.

That’s a trend you can hear right across the language translation industry. This year, the market is expected to pass $75 billion. By 2028, the market is expected to pass $95 billion.

Trends in the sector show it’s not just the major multinational corporations fuelling the growth – more and more small and medium-sized businesses are seeking language translation services. Language localization and regionalization are important ways to connect customers, suppliers and partners across ever-widening global markets and supply chains.

And while machine translators and AI translate tools can be used for fast translations, it’s said by many professionals that most platform translations should still be reviewed and edited by humans to eliminate language errors and hallucinations, and to make best use of spoken communications.

# # #

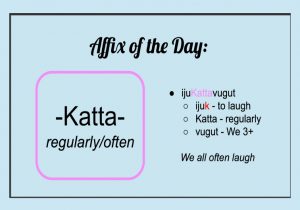

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the Ottawa-based national organization representing some 70,000 Inuit here in Canada, works to preserve and promote language and literacy. Its Affix of the Day generator has good advice and observations.

-30-

Related:

Speaking the Language: The Latest in Translation Tech Bridges the Gap