Canada is where artificial intelligence was invented, he said, so we have every right to lead the way.

But leading the world in worry and apprehension about the risks associated with AI has its own risks.

According to a new report about global AI adoption from KPMG, Canadians are understandably concerned about the risks associated with artificial intelligence programs and systems.

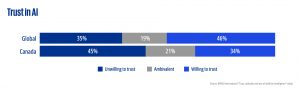

Trust, attitudes and use of artificial intelligence: A global study 2025 surveyed over 48,000 people in 30 advanced economies and 17 emerging economies, including 1,025 people in Canada, about their trust, use and attitudes towards AI. Trust in AI (CNW Group/KPMG LLP)

When it comes to our trust in AI systems, we ranked 42nd out of 47 countries surveyed. Among the advanced economies studied, Canada is 25th out of 30 – put another way, we’re among the Top Five worldwide in not trusting something ‘we invented’.

Nearly half of us think the risks of AI outweigh the benefits: there’s a concern about losing jobs in a changing workplace; worries about bias, about security, about the loss of privacy, damage to the environment, and the misuse of intellectual property, among other concerns.

Listening to the “godfather of AI”, those worries are probably a good thing.

Geoffrey Hinton, the British-Canadian computer scientist who was awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics for his foundational work on neural networks and artificial intelligence, actively and vociferously warns people about what his work has wrought.

Others say the lack of trust in AI is really a lack of education and understanding. Being overly risk averse about AI will stifle innovation, these worriers say, and hold the country back from being competitive in challenging times.

Hinton spoke during Toronto Tech Week, at a University of Toronto event called Frontiers of AI: the U of T professor emeritus and Nobel laureate was in conversation with another Canadian leader in AI, Nick Frosst, who is co-founder of the Toronto-based AI language processing startup Cohere.

“We – you – invented this technology,” Frosst saluted Hinton and his work during their on-stage conversation: “Canada has every right to be a leader in it.” Hinton worked for some ten years at U of T and Google Brain, where Frosst was his very first hire.

Despite both their successes (or because of them), Frosst and Hinton have some agreements and disagreements about AI, generative AI, and LLMs (the large language models that underpin artificial intelligence). They see at various times enormous potential or great risk in what they do agree is a “disruptive technology”.

Whether or not it now has – or soon will have – truly human cognitive capabilities or truly human subjective experiences is one point of contention between the two.

While not saying so, it may be disagreements and differences about just what AI is and how it works, such as those found among AI leaders here in Canada and elsewhere, that fuels some people’s lack of trust in the technology, as quantified by KPMG: ‘If the inventors and industry leaders can’t agree on what this is, how can we?’

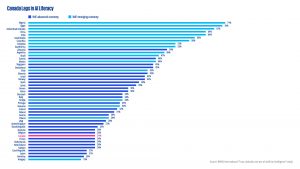

The report did say that that Canadians have among the lowest levels of AI training and literacy – and it may follow, trust – in the world.

Canada Lags in AI Literacy (CNW Group/KPMG LLP)

The research from KPMG International and the University of Melbourne shows a real need for increasing our investments in education, training, and yes, regulation to build up trust in AI as a safe and strategic tool to boost the economy.

As an educator, Hinton also sees a need for knowledge and training, perhaps of a different sort: “My role is persuading the public to understand this stuff is dangerous!”

Frosst described it differently, and referring to the societal disruptions felt during the Industrial Revolution, for example, he said, “AI will test the general reliability of our social fabric.”

We will need robust social systems and strong safety nets to cope with the changes AI will have in the workplace and on our workforce, but Frosst says, “We do that well in Canada.”

He thinks the country can maintain its AI leadership with continuing investment (there is a good VC culture here, Frosst says, as his company Cohere has raised some $500 million since inception), and by helping educate people by building an understanding of how AI works and how it works for them.

The national climate is important for AI, and trust will be important both in terms of investment and regulation.

Hinton could not resist a good-natured jab at his one-time protégée by noting that big tech – he stared with a smile directly at Frosst – does not want regulation. “Big tech is like big oil,” he said with a laugh and an apology. “They don’t want regulation; well, they say ‘We’re not against regulation; we just don’t like that one’,” he chided.

(Canada does not now have a federal regulatory framework for AI in place, but the government has established a Voluntary Code of Conduct on the Responsible Development and Management of Advanced Generative AI Systems.)

In fact, during Toronto Tech Week, the new federal AI minister, Evan Solomon, said that AI regulation from the feds is coming, but it will not be overweight or burdensome. The outcome of various AI-related lawsuits (underway here and around the world) should help inform the policy with legal and marketplace precedent. One such case is against Cohere, which is being sued for alleged copyright and trademark infringement.

If AI companies had to follow proper standards, governance, and regulation, more than 80 per cent of Canadians say they would be more willing to trust AI systems, KPMG found. With good mechanisms for human intervention to override or correct AI-generated output, trust could grow.

Likewise, having the right to opt out of one’s personal data and interactions being used to train AI models (and perhaps a licensing framework for the consent-driven use of all that other content that’s poured into those large language models) could boost trust and confidence.

There needs to be an accountability mechanism if something goes wrong, say many AI users and observers. Reliable (third-party, all Canadian?) monitoring of AI output accuracy and reliability could also contribute to us having greater confidence in our own invention.

# # #

Geoffrey Hinton (at left), Norah Young (middle), and Nick Frosst (at right) in a video screen grab. Their on-stage conversation, “Frontiers of AI”, was held at U of T’s Convocation Hall June 25.

Artificial intelligence adoption is capturing public imagination and sparking important debates and critical conversations about whether and how AI should be regulated and what guardrails need to be in place to protect society.

One such conversation took place during Toronto Tech Week, a local non-profit initiative led by the Canada Tech Week Organization; it was held at Convocation Hall and live streamed.

Professor Emeritus and Nobel Prize winner Geoffrey Hinton was joined on stage by Nick Frosst, Co-Founder of Cohere, to talk about the opportunities, challenges, and obligations when leveraging the power of artificial intelligence. The conversation was moderated by CBC Tech Journalist and Broadcaster, Nora Young.

Asked to comment on the transformational nature of the AI explosion, Hinton smiled: “Well, Nick used to be an intern in my lab. Now, he’s a billionaire!”

Frosst demurred, but later noted that, “Yes, I do own an LLM company. I also write lyrics (he’s in the indie pop band, Good Kid).”

Drawing a clear line of distinction between AI and human creativity, he said “I do not use the model to write lyrics. I do not want to write lyrics faster. I’m not interested in the efficiency of self-expression; I’m interested in self-expression.”

(At this, a round of applause swept through the audience. The session was just about ending, and I could think of but two responses at the time:

Excerpt:

“Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

Excerpt:

“A just machine to make big decisions

Programmed by fellows with compassion and vision.We’ll be clean when their work is done

We’ll be eternally free yes and eternally youngWhat a beautiful world this will be

What a glorious time to be free.”

-30-