It’s hard to believe that some of the smartest talk about today’s technology, and some of the most insightful advice about AI, came to us more than three decades ago!

Some might be surprised the insights came from a woman (though they do so at their own risk) and it’s a shame so few know about her (the risks are again apparent).

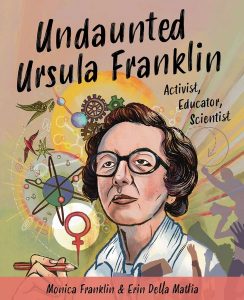

Before smartphones, before social media, before gen AI came Ursula Franklin. Scientist, metallurgist, women’s advocate, pacifist, technology commentator, wife and mother.

This Canadian’s vision and perspective on the social impacts of technology overall (much less the at-the-time undiscovered tech tools and toys of today, including but not limited to generative artificial intelligence) are more relevant, more needed now than ever before.

Fortunately, perhaps ironically, her insights about technology are available today thanks to technology, many preserved as digital audio streams. Collections of her work and writings are accessible at the University of Toronto, where she worked, and at Seneca College, to which many of her valuable materials were also donated.

A series of 1989 broadcast lectures written and delivered by Ursula Franklin are transcribed in a book of the same name.

There’s much to be learned from a series of public lectures called The Real World of Technology (streaming online and reproduced in a book of the same name), during which she painstakingly but devastatingly described the double-edged nature of technology.

From 1989, her words come to us today almost hauntingly, She saw technology as either work-related or control-related. She also differentiated among the holistic, the prescriptive – and what she hopefully describes as the redemptive – qualities of technology.

Work-related technologies, like the typewriter, are designed to make tasks easier. Simple enough. Electronic typewriters and then computerized word processors made typing even easier. Great.

But when word processors became computer workstations, networked together as part of a much larger and integrated technological system, Franklin says the typewriter became a control-related technology.

It’s not the words that are being processed, it’s the worker: “Now workers can be timed, assignments can be broken up, and the interaction between the operators can be monitored,” she warned.

Monitoring employee interaction in the organization is one thing; monitoring people’s interaction across global networks yet another.

So it’s with anticipation, not surprise, that Franklin felt most modern technologies were command- and control-related tools, more so than supportive work tools.

Stretching that impact even further, Franklin explained how “Many technological systems, when examined for context and overall design, are basically anti-people. People are seen as sources of problems while technology is seen as a source of solutions.”

With AI advocates today touting increased efficiency and productivity for the corporation, enhanced experiences for customers and employees, greater convenience for busy people, her words still ring true.

* * *

Born in Germany before the Second World War, her parents were interned in concentration camps and she was sent to a labour camp (her family was reunited but soon fled Germany and came to Canada).

Life experiences steered Ursula Franklin toward a life of compassion and sensitivity for others, as described in a book co-authored by her daughter.

She became a scientist and an engineer at a time when women were not welcome in those domains. Throughout her public life, she stood up for equality, for the most vulnerable among us (she would be dedication to women’s issues and social causes throughout her life). She advocated for democracy and promoted protection of the environment when many did not know they were at risk.

Such life experiences and the insights they brought steered her toward a life of compassion and sensitivity for others, and for those impacted by technology.

She would celebrate the impact of what she called “holistic technology” because she said it empowers professionals – people – to retain control over their creation or production process. Individual decision-making is embedded in the process itself. Think of a potter, she said, who chooses the type of clay, controls the spin of the table, sets the temperature of the firing oven, decides on the look of the glaze and the colours in the design of a hand-made mug. Decisions are made as the work progresses, and while one maker oversees the whole process, he or she can interact and consult with other craftspeople.

That’s quite different, Franklin said, from “prescriptive technology”. It tends to divide and sub-divide work into an assembly line of small, individual tasks which are usually done in specific order by different people. Franklin felt technologies forced creativity and individuality to become controllable and predictable. Interactions and consultations with others are less valuable, even discouraged, when separate tasks are done by separate workers.

So Franklin proposed the development and use of “redemptive technologies”, ones that are shaped by a social precedent, not a technological one. She said the best world of technology would be the one in which a demonstrated stewardship for people and for nature was ingrained.

She spoke and wrote in The Real World on Technology that we should ask of any “public project” whether it: (1) promotes justice; (2) restores reciprocity; (3) confers divisible or indivisible benefits; (4) favours people over machines; (5) maximizes gain or minimizes disaster; (6) favours conservation over waste; and (7), whether the reversible is favoured over the irreversible.

(The latter point contrasts, say, our ability to recall contaminated meats, for example, with our ability to recall dangerous AI tools.)

* * *

U of T Professor Jane Freeman collaborated with Ursula Franklin on a book of Franklin’s previously unpublished lectures and interviews, which was published in 2014.

Franklin died in 2016, at age 94. She was honoured many times throughout her long career, including being appointed to the Order of Canada. She received both the Governor General’s Award and the Pearson Medal of Peace. She was the first woman to be named University Professor at the University of Toronto, that university’s highest position, and she was granted honorary degrees from several other Canadian universities.

And she has a street and a school named after her in Toronto.

Ursula Franklin Academy (UFA) is a unique high school where advanced liberal arts and sciences classes are delivered to a student body capped at around 500. The school makes every effort to integrate technology into the curriculum, and to reflect much of Franklin’s own teachings and perspectives on the topic.

Students can gain critical digital literacy skills attending UFA, school officials say. Students are encouraged and empowered to look thoughtfully at a world increasing shaped by technology, taking cues from the school’s eponymous visionary who always advocated for valuing the human above the technology.

Her words and teachings are not just for students, of course, but for any of us impacted by technology. Like all of us.

“Technology has built the house in which we all live,” she wrote, “today there is hardly any human activity that does not occur within this house.”

And houses come with a mortgage which must be paid.

# # #

Canadian scientist, activist, author, and educator Ursula Franklin. Photo credit: University of Toronto Archives.

-30-