Digital techniques and technologies, and the information resident in the crowd, are being used to create a new kind of online archive in which valuable historical artifacts are being collected from untapped public sources as much as existing private collections.

Educators, archivists and technologists are working together to build what are community collections as much as historical archives. But while the names may be different, the purpose, feature and functions are similar.

The new World Wars Aboriginal Veterans Portal (WWAVP) is now online.

A great new example is the Canadian-launched World Wars Aboriginal Veterans Portal; it’s seen as the largest and most comprehensive source of data about aboriginal soldiers of the First and Second World Wars. The WWAVP already documents the lives of 8,300 individuals through images, biographies and transcriptions of all known or accessible biographical details about the soldiers.

As it grows, developers will add content and surviving documentary records sourced from the actual soldiers, or their families, to the site. Submitted material can include diaries, photographs, administrative records, personal correspondence and more. New content will continue to be added to the site through the spring of 2017. Site visitors and users can currently query the database using a variety of fields, including name, geographical locations, nation or band, and military units.

The free and publicly accessible website came from Canadiana.org, a non-profit digital archive, which received a grant from the Department of Canadian Heritage through the World War Commemorations Community Fund.

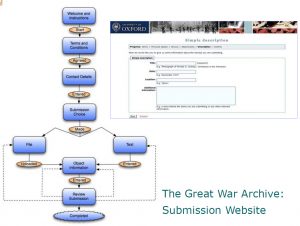

As Daniel Velarde, Communications Officer with Canadiana.org, explained in e-mail correspondence with whatsyourtech.ca, the model for the project is essentially a crowdsourcing concept pioneered by Oxford University.

“Basically, Oxford was able to produce a large-scale collection of surviving First World War records by inviting the descendants and relatives of soldiers to scan/contribute their records themselves, using household devices,” Velarde described.

Household is one of the keys to a community collection: in the past, developing a digital or online archive meant having access to sophisticated and expensive flat bed scanners or micro-lens cameras. Digitization projects were often led by large organizations, such as a library, museum, or university. Significant funding was often required, as well as the access to or ownership of a major collection in the first place.

But as the organizers at Oxford point out, things have changed.

Digitization can now be undertaken by the masses, at home or almost any other location, because almost everyone has a digitization device in their pocket nowadays – thank you Apple!

Stuart D. Lee and Kate Lindsay also point out that our attitude to and familiarity with searching and browsing techniques have also developed, and we are much more comfortable navigating interfaces, catalogs and advanced search boxes – thank you Netflix!

Finally, of course, there are many more ways to make digital content available these days, not just new devices, but social networks and third-party content sharing sites, like Flickr and Flickr Commons.

What’s more, the team at Oxford developed and released a special software tool for building community collections, openly and freely distributed, called CoCoCo.

What’s more, the team at Oxford developed and released a special software tool for building community collections, openly and freely distributed, called CoCoCo.

It’s about making the uploading of content and objects easy enough for almost anyone to do, following a set of simple steps that explains the process, gathers some basic descriptive metadata, and explains the license conditions.

Contributors are asked to share their contact details (which could be kept anonymous) and information about author (the person who “created” the item), creation date and place (if known), content type (using a series of keyword prompts) and other helpful information like personal notes and related anecdotes.

For the Canadian project, as Velarde described it, initial content was assembled at professional standards either in-house or by a third party provider, with quality assurance, post-processing, more QA, cataloguing, uploading to a delivery system, and so on carefully performed throughout the development phase.

“Generally, our preferred output for preservation masters are JPEGs at 300 dpi, from which we can generate derivatives (PDFs, etc.),” he detailed. “For this project the standards are somewhat relaxed: we aim primarily for clarity and legibility of the digital images.”

Canadiana worked with partners in the Aboriginal/Indigenous community, and it was Wampum Records, a leading Aboriginal issues research organization, that helped review the files and advise donors on digitization methods, where appropriate.

Asked to estimate some of the tech specs that the site anticipates needed, Velarde said he doesn’t expect the total data produced by this project to reach the (TB) terabyte range: “Generally, we’ve found that one TB of digitized cultural heritage content equals about 500,000 scanned pages,” more than is currently anticipated.

“It’s hard to project total traffic at this stage, but similar resources produced by Canadiana average in the tens of thousands of sessions per month,” he noted, adding that Canadiana is an independent non-profit organization with servers located at a variety of institutions.

“Even assuming that content (photos, the odd letter or other record) is found for every soldier in the database, we would remain well below that (TB) threshold.”

Clearly, the project is motivated by recovering and sharing unique historical records and untold stories, rather than the sheer volume of data. It’s about honouring the soldiers and preserving a people’s memory as much as creating an extensive online study archive.

In the first phase, Canadiana.org meticulously collected and transcribed thousands of pieces of data about Canada’s Aboriginal or Indigenous World Wars veterans. All data is drawn from verified primary sources, including Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) service files and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

The second phase for the WWAVP, as described, will source content from the public, including individual soldiers, their friends and families. It’s the kind of content to which, with rare exceptions, the rights and copyrights are held by the contributor, and from which the perspective is quite unique and very telling.

As large amounts of data filters into the database, it is already becoming possible to sketch a sociological portrait of aboriginal soldiers in history. Of a sample of 2,350 CEF individuals with known occupations, about 20% were labourers, 36% farmers or farmhands, 3.7% fishermen, 3% hunters, and 4.3% trappers. Some 15 clerks, 38 carpenters, 14 axemen, and 10 cowboys stood out among the CEF’s aboriginal contingent; they ranged in age from 15 to 49.

Along with the new WWAVP website, there are other online sources of information, including the Canadian Aboriginal Veterans website. WWAVP estimates that 12,000 aboriginal (Inuit, Metis, and First Nations) people served in Canada’s armed forces during the First and Second World Wars.

Along with the new WWAVP website, there are other online sources of information, including the Canadian Aboriginal Veterans website.

-30-