TomTom has become a renowned brand for mapping and navigation, but getting to that point required mapping and updating the geography to help drivers get to where they wanted to go. At an exclusive press event in the Caribbean island of Martinique, we got a firsthand look at what goes into mapping a place virtually from scratch.

TomTom has become a renowned brand for mapping and navigation, but getting to that point required mapping and updating the geography to help drivers get to where they wanted to go. At an exclusive press event in the Caribbean island of Martinique, we got a firsthand look at what goes into mapping a place virtually from scratch.

When TomTom acquired Tele Atlas, it got what TomTom co-founder and chief technical officer, Peter Frans-Pauwels, called the “mother load database”. Tele Atlas offered satellite base maps of pretty much the whole world, albeit with no distinct information. That’s where TomTom comes in.

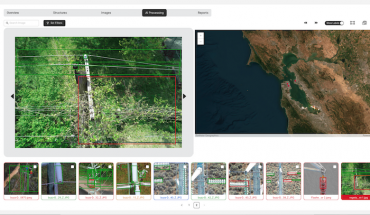

Our job was to observe and gain an understanding of what goes into building a map when you have no information on it. We could see roads on TomTom navigation units, but no street names, no speed limits, points of interest — nothing. The map, for all intents and purposes, was barren, and it was full of mistakes. Newer roads were either missing or wrongly displayed. There was no signage, roundabouts weren’t shown, and even distinctions in roads (paved vs. dirt or gravel) weren’t obvious.

While it may be natural to assume that TomTom deploys something like a Google van with 360-degree cameras mounted above to capture everything they see, the truth is not quite like that. The first step is to ensure that all roads are accounted for, which means that a TomTom rep would not only have to drive around every road they could find, but also verify and collect as much data as possible using TomTom devices, a laptop with proprietary software and even an iPhone app called Field Editor.

Martinique is not a huge island at about 1,100 sq. km, and that figure is reduced even further since some of the terrain is mountainous and tropical rainforest. But save for some major thoroughfares, there is a lot to put into the map. TomTom does this in a layered format that requires input from the ground all the way to data centres in India where the many terabytes of data taken from the ground are literally couriered over to India for processing, since it would take an eternity to try and upload that via the Internet.

For an island the size of Martinique, it would take roughly two months to capture all the base data of roads, according to Tom Howze, who used to work in the field regularly but is now in TomTom’s head office in Amsterdam. As we drove along a predefined route from the eastern coast of the island over to the west, we got to actively see some of how this all works. In our van were TomTom navigation units, a laptop, odometer, 360-degree camera and a laser scanner for 3D imagery.

The data stored on the laptop is extracted and then couriered over to India. But Martinique is one of those unique cases where sending a decked out TomTom van wouldn’t make economic sense, so in a case like this, a lone TomTom rep in a rental car with a laptop and iPhone would suffice.

Driving around, we could see that the base map was missing a lot of information. Certain roads weren’t in line with where we were actually going, and with the use of Field Editor, TomTom’s field operatives could snap photos of everything from speed limit signs, street signs, junctions, points of interest or anything else deemed important to note. The location data from the image becomes part of the mapping data via points listed on the map. Using the Cartopia program on a PC laptop, we could see the various points that were marked during the excursion the following day, after they were processed.

What’s interesting about this process is that it uses few people on the ground, and sometimes requires referencing data with locals at points of interest. It could be an address that isn’t clearly marked, or a structure that doesn’t show a particular name. TomTom operatives on the ground must make these connections to ensure the map data is as up-to-date as possible.

There have been a number of cases in other countries where operatives had to go and verify a number of new road openings or other changes to the map that hadn’t been included. When sending someone isn’t necessary, TomTom operatives will call local authorities to get the info they need.

This focus on precision is part of the company’s strategy moving forward, Pauwels says. The reason why is because the true value is in the maps, not the hardware that displays the map. So, despite portable navigation devices being cannibalized by smartphones, maps will actually increase in sophistication on mobile devices.

Part of how we reported errors included using TomTom’s existing MapShare feature, which has been a staple for years now. This allows users to report errors on the map and have TomTom assess and fix them upon each subsequent update. Pauwels says that a small number of users can account for a majority of the changes needed in any given location. These active users are internally referred to as “MapShare Heroes”. HD Traffic, which is TomTom’s real-time traffic update service, runs on a cellular connection that a user subscribes after the first 12 months. This takes anonymous data from all drivers using TomTom devices or software (iPhone or iPad) while driving and uses algorithms to determine what traffic conditions are on all roads and what the best routes would be to get from one point to another.

The number of devices using HD Traffic still doesn’t span the gamut of the company’s lineup, and in an island like Martinique, traffic may never see the gridlock we’re accustomed to in North America. But interestingly, Pauwels adds that just 10 percent of drivers with good information can reduce traffic for everyone else by 15 percent. He even says that 50 percent of all routes are changed from their original directions because of this technology.

But this would all be useless, if not for the maps themselves. From the base, to street names, street types, signage, points of interest — a fully detailed map like the ones consumers use could take as many as six or seven layers of information before completion.

The crowdsourcing side of mapping is likely the next big thing in maps, maybe other than 3D scaling. Eventually, maps will look like real-life 3D models of entire city structures and road networks, but for now, building a good map, even in a sunny destination like Martinique requires time and effort — and a little help from the people who use them.

In fact, TomTom even has a contest right now called “Mapping Paradise”, where lucky winners can bring their families or a group and map one of five tropical islands: Fiji, St. Lucia, Mauritius, Seychelles and Cape Verde. On top of that, each winner gets $15,000 for their troubles.