The first message was ‘Merry Christmas’, but now we can text out ‘Happy Birthday’, too!

The first send on the short message service (SMS) platform was December 3, 1992, and in the twenty subsequent years, the technology has grown into not only one of the most frequently used communications media, it is also a multi-billion dollar business.

It’s spawned a new short-form language, or at least a collection of abbreviations that act as a language, and even non-English speaking users have helped ‘anglicize’ all sorts of common terms, phrases and shortform salutations, like “lol”, “u”, “brb”, and “gr8”.

SMS has spawned new styles of social interaction, too: some are fun, even frivolous, like micro-blogging or ‘Flash SMS’ ing. Some are potentially more dangerous, like texting while driving, or even sexting.

Yet some wonder if text messaging as we have come to know it will even last through the New Year, much less another 20.

When UK-based researcher Neil Papworth first used a PC to send the text message “Merry Christmas” to fellow technologist Richard Jarvis back in ‘92, the two men were building on a multi-national collaboration that worked to develop a framework of standards and protocols for fast and efficient tele-communications between fixed line or mobile devices.

Once they had achieved a certain level of technical success of the system, the underlying technology was made available at no charge around the world.

SMS started out as a kind of organizational notification systems, but young people soon picked up on the platform big time as a cheap way of sending messages person-to-person.

SMS embodies a framework of standards and protocols for fast and efficient tele-communications between fixed line or mobile devices.

Mobile operators did price SMS lower than regular voice calls, and this helped drive greater adoption and more usage. Cheaper bundles and unlimited usage were offered by the providers, and the perceived cost savings extended the SMS popularity beyond the early adopters.

Over the years, mobile operators and telco providers have seen huge upticks in revenue and profits from the global increase in SMS revenues and traffic. Advertisers and retailers have picked up on the platform, and use it to distribute direct marketing messages, product promotions, even payment due date reminders.

Estimates now are of close to four billion active SMS text messaging users worldwide, with some 6.1 trillion SMS text messages sent in 2010.

And all that chatter has led to well over a $100 billion in global revenues.

Now all those revenues have also caused a stir, too, especially here in Canada.

In fact, the business watchdog agency that fights for open competition and market fairness has taken on our biggest telcos and text service providers a lawsuit targeting misleading costs and advertising activities.

Canada’s Competition Bureau is suing Bell, Rogers, Telus and the industry group that represents them in an attempt to make them stop advertising premium texting services and refund consumers who were charged for the messages.

In the suit filed in Ontario Superior Court, the bureau is seeking $10 million each from Bell, Rogers and Telus, and $1 million from the industry group.

That case is apparently still under investigation, even as SMS traffic and revenues are in decline elsewhere in the world, as the penetration of smartphones and mobile broadband grows. Some say SMS-providing telcos are losing billions in revenues every year.

Linguist David Crystal takes a long hard look at the text-messaging phenomenon and its effects on literacy, language, and society in his book.

Smartphones and mobile communication platforms, highly competitive and mostly proprietary as they are, are combining with new social networking tools and free messaging services and proving to be strong and attractive messaging alternatives: WhatsApp, Fring, KakaoTalk and Nimbuzz are among the competitors.

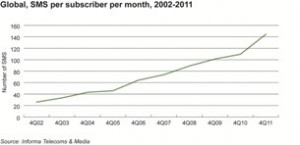

But by no means is it all doom and gloom for SMS, says Pamela Clark-Dickson, senior analyst for Mobile Content & Applications at Informa Telecoms & Media.

In fact, SMS traffic continues to grow year-on-year globally, she notes, adding that Informa forecasts that global SMS traffic will increase to 6.7 trillion messages, representing a year-on-year increase of 13.6%, up from 5.9 trillion messages in 2011.

SMS traffic will increase to 6.7 trillion messages, representing a year-on-year increase of 13.6%, says telco research company Informa.

So, there’s still tens of billions in revenues at stake.

Also, in emerging markets in Africa, Asia and Latin America, the penetration of smartphones, mobile broadband and home-based Internet-enabled computers is relatively low. So SMS is like an essential service, enabling not only commercial activity like mobile banking and payments, but also for sharing vital health and safety information.

SMS is increasingly being used in innovative and imaginative ways in these markets, Clark-Dickson describes, and it will be some years before free messaging applications can achieve the same level of penetration as SMS.

As ubiquitous as they’ve been, and may still be, there’s a certain security or privacy risk with SMS. Contents are easily known to the network operator and personnel, so they should really not be used for confidential or secure communications.

Some providers do implement SMS gateway and secure connectivity tools when routing messages, but there again, the contents are exposed to gateway providers, and to any commercial, regulatory or legislative rules.

-30-

submitted by Lee Rickwood