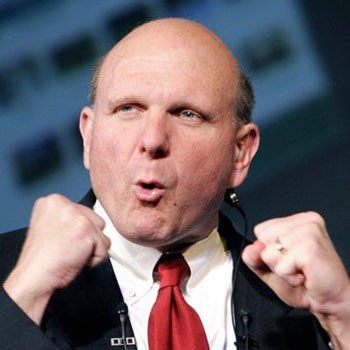

Steve Ballmer surprised the tech world by announcing his resignation, effective sometime in the next 12 months, and while his tenure saw some incredible change, he was almost always on the wrong end of that evolution.

Steve Ballmer surprised the tech world by announcing his resignation, effective sometime in the next 12 months, and while his tenure saw some incredible change, he was almost always on the wrong end of that evolution.

As employee number 30, and an old pal of one Bill Gates, Ballmer was, at least from an outsider’s perspective, in the right place at the right time. Since he joined in 1980, Microsoft arguably became one of the most dominant corporations in history, especially leading up to the new millennium. From DOS came Windows, and from the Internet came Internet Explorer. Office became so ubiquitous in the office and home that practically no one could compete. Heck, even U.S. regulators looked to possibly force a break-up of the company, while European regulators went the antitrust route for years.

Indeed, when Ballmer took over as CEO from Gates in January 2000, Microsoft seemed unstoppable. Apple was still a shadow of its former self. IBM wasn’t known as a consumer brand anymore. Microsoft was the ultimate software company, and as PCs continued to sell in growing quantities, the windfall from all those licenses filled the company’s coffers in a way that must have made Ballmer tear with joy.

Unfortunately, that windfall is precisely why he didn’t drive the company further into irrelevance than it already is in some market segments. Businesses and their users have long been known as a conservative bunch, and those pricey licenses kept rolling in, just like they were from new consumer PC purchases. The revenue generated from Windows, Office and the company’s server products were likely a big reason why the list of failures Ballmer presided over didn’t sink Microsoft deeper into the abyss.

The Xbox was a great success for the company, and much of that is owed to the fact it has its own identity — meaning it doesn’t run or even look like a Windows product. The console (including the Xbox 360) was innovative in how it handled online gameplay and content, and also tinkered with home media capabilities, like streaming and live TV. Microsoft took on established gaming hardware brands like Sony, Nintendo and Sega and performed extremely well. For that, Ballmer deserves credit, since it’s hard to see what kind of direction Gates might have pointed towards, given his reported dislike for the initial Xbox concept.

But in just about every respect, Ballmer not only failed to capitalize on opportunities, he found original methods in putting his foot in his mouth. But before we get to that, let’s look at how it all came to this.

Windows Vista is his biggest regret, according to several interviews Ballmer has given in the past. It should be, because it opened the door wide open for Apple to launch a clever ad and marketing campaign that played on the OS’s most grievous flaws. It also came at a time when the market started to change with savvier users. Vista was a dud, and people knew it from the first time they used it. Bloated, annoying and lacking identity, the OS sullied Microsoft’s reputation and standing at a time when the heat was only beginning to simmer.

The same month Vista launched to the masses, Apple unveiled the iPhone. Ballmer was at CES 2007 at the same time, touting the world of Windows like a TV evangelist. When asked about the iPhone, he scoffed at the “$500 phone” and later said that it had “no chance” of gaining significant market share. The numbers speak for themselves, so there’s no need to rehash that, but this kind of arrogance and lack of vision is ultimately what characterized his tenure at the top. When the iPhone first came to market in mid-2007, Windows Mobile had peaked at 50% of sales in Q2 that year. Its market share was sitting at a very respectable 42%, according to NPD Group at the time. Four years later, it was 3%.

Whether or not Ballmer failed to see the potential mobile devices and software had in the short- and long-term isn’t clear, but what seems to be obvious is that it was either not taken seriously enough or he didn’t want to rock the boat with his vendor partners. Whatever the case, Microsoft had squandered a golden opportunity long before BlackBerry did. And now, those two companies fight for scraps, while Apple and Samsung collect all the profits.

The Zune was launched at a time when Apple and some other manufacturers had already correctly calculated that smartphones would essentially cannibalize iPods and MP3 players. The product line was practically dead on arrival, though its saving grace is that the impressive user interface is now a Microsoft staple on Windows Phone and Xbox.

That said, for the biggest software company in the world, Ballmer also missed out on things like an online music store (iTunes), mapping (Google Maps), streaming (too many to list) and a modern mobile OS (what Windows Phone finally is now). Internet Explorer once had market share in the 90 percentile, but now struggles against nimbler and smoother competitors. Support for Windows XP had to be extended to 2014 because of the blowback from Vista, which made businesses reluctant to upgrade to the much better Windows 7.

He mocked the MacBook Air for not having an optical drive, almost completely ignoring the engineering feat that had been achieved when none of his hardware partners had brought anything like it to market. When the iPad was unveiled, Ballmer and Gates went on about how Microsoft had been in the tablet business for years, seemingly without tacitly acknowledging the context, which was that Apple had changed that business.

And when he wasn’t criticizing Apple, he left some contempt for Google, the company that outmaneuvered him on almost every turn. That contempt may not have been overtly stated, but it also didn’t have to be because he never really won a battle against them anyway. Bing is a nice search tool, but it’s not a search giant like Google is. Microsoft might have had the chance to come up with something like turning MSN Messenger into a Facebook-style social network, but instead, Facebook came from the grassroots, just like Microsoft did in the 1970s.

With Surface, Ballmer wanted to get into the tablet mix, surprising many when he announced that the company would be making its own Windows 8 tablet. It was an interesting design and a bold initiative, but any measure of success still seems elusive. First, there was the $900 million write-down covering the Surface RT inventory no one seems to want, and second, is the $900 starting price point of the Surface Pro. Somehow, Ballmer thought that a tablet with an unproven version of Windows — priced higher than an iPad — was a recipe for success at retail. The numbers will tell that story soon enough.

If there is a legacy to bestow on Ballmer, it’s one of failure. He inherited an empire with the resources to truly change the world, only to lead from a position of weakness when hungrier companies took the reins. Gracious and classy in his exit as he was, Ballmer leaves behind a company that must change considerably in order to be relevant as a consumer brand. Even if it ultimately doesn’t in the coming years, the blame will fall largely on him.

And the irony is that only one Steve will really be remembered in this era, and his last name was Jobs.