A new computer algorithm developed at the University of Toronto is part of an entire portfolio of new products and services for facial recognition, skin analysis and virtualized visualization.

By mapping, analyzing and processing data about the structure and dimensions and other elements of a human face, developers are working in a space defined not only by software tools and mobile computing devices, but also human physiology, psychology, and neuroscience practices.

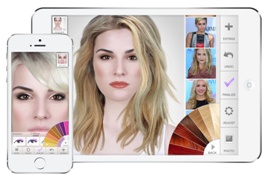

ModiFace offers new mobile beauty and make-ups apps based on its proprietary algorithm.

Commercial end user applications include anything from picturing how anti-acne treatments might work, to an even more glamourous makeover that shows how applying different mascaras, eyeliners and make-up styles might look.

Corporate applications are being embedded into digital signage and out of home advertising displays with built-in cameras and wireless connectivity features, allowing marketing messages to be tailored to a passerby’s age, sex or even general emotional demeanour, all of which can be determined by facial recognition software.

ModiFace is one of the leading companies that is now applying academic facial recognition research to such products, and the company is applying its inventive algorithm to digitally analyze faces captured in digital images of almost any type.

Initial research on the facial recognition algorithm actually began at Stanford University nearly fifteen years ago. Work on automatic face analysis tools and techniques continued at the University of Toronto, and a signal processing algorithm that won a world-wide innovation prize was born some five years later, and development continues at the Mobile Applications Lab, a dedicated campus space for mobile application development.

Today, technology from Modiface Inc. is the basis of a significant patent portfolio on skin analysis and visualization, and it’s driving more than 100 online and mobile applications compatible with all major platforms.

Parham Aarabi is a professor, entrepreneur, and founder and CEO of ModiFace.

MakeUp is the company’s makeover app, with photo-realistic tools to change and adapt make-up styles virtually, on-screen, before actually applying them. The app includes tools to visualize new hair styles and colours, lipstick and glosses, eyeliner and eyelash treatments, and more. The styles can be applied to a selection of model’s faces, or to an uploaded user image.

The ModiFace mirror app works in real-time

Once the most desirable make-up look is chosen and actually applied, Aarabi has developed a real-time 3-D virtual mirror technology for ModiFace, letting users tap on the screen interface to create and see a new look in real-time.

“There’s no uploading. There’s no calibration,” Aarabi described. “You simply look at the camera, and you see your face.” Even if the user moves their face around quickly, or poses at extreme angles, the technology tracks the face and shows how make-up applications will look, he added.

Another application demonstrates the acne-clearing power of branded skin products, right on a photo of the user.

With ClearCam by Murad users can easily snap, clear and share picture-perfect selfies, having used the app to target blemishes and apply a time-lapse swipe to their face to see projected results over a one or two week timeframe.

Once the user has selected their desired treatment, they have the option to

The facial transformation can be shown with before/after images, and any new looks can be saved to the device and shared with friends and family.

Users can try out different make-up styles and products using ModiFace.

Facial recognition algorithms like those from ModiFace, and facial coding technology from another firm called from Affectiva are also being used in large scale outdoor advertising campaigns from major companies such as Unilever and Coca-Cola.

Such platforms use proprietary software to interpret viewers’ facial expressions and to make actionable judgments about how viewers feel about the ads they see.

That’s because software and hardware tools can not only capture, mimic and render out a person’s appearance, they can now begin to assess behaviour from static imagery.

Researchers say they can very accurately identify and evaluate faces, based on a nine-point computational algorithm, one that is not thrown off by severe camera angles, eyeglasses or facial hair. Age, sex, cultural background and emotional attitudes are easily determined by analyzing such data points.

That’s been key to other, non-commercial, uses of the technology.

In some jurisdictions, facial recognition is a big part of the self-policing of gambling addicts. It is used to identify those who have signed up for remedial care is dealing with a gambling addiction.

Of course, police and law enforcement agencies use such tools to identify possible criminal activities, such as during large mass protests or demonstrations, even as information and privacy commissioners continue to review the use of these kinds of facial recognition technology to ensure that it complies with privacy law.

-30-

Parham Aarabi is a professor in The Edward S. Rogers Sr. Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering; along with his students including Ron Appel and Amin Heidari (pictured), he’s developed a number of computer algorithms that have led to new commercial product and service introductions.