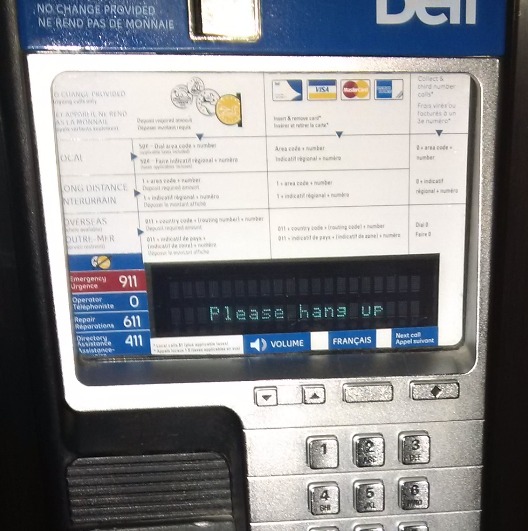

Payphone use has declined over the past decade, but there is still a strong need for public phones.

Whether you carry a cell phone or not, whether you wear the newest watch tech or not, publically accessible payphones do have a on-going value, beyond being one of the last examples of shared social consciousness and communal convenience.

Will Canada soon see its last public payphone?

At a time when almost everyone carries their own phone, many question the need for payphones in public spaces. Telecom operators and telephone companies certainly do – they are reducing the number of available public payphones annually, even as they ramp up wireless telephony services sold to individual consumers and private users.

But there is recognition in some quarters that payphones do provide a societal benefit because of their (potential for) accessibility, privacy and economy, such as the low one-time per-use cost and unlimited time for local and toll-free calls.

Payphones also provide free 911 calls, although most emergency calls these days come from mobile phones (bringing their own set of issues and challenges).

So Canada’s broadcast and telecom regulator, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, is calling phone service providers and telling them about new rules that they must follow when removing public phones in a given community.

The Commission wants phone companies to notify the affected communities, including municipalities and First Nations, before removing the last public phone, or before removing any payphone from areas where wireless service is not available.

As it has for several controversial telecom and technology-related issues, the CRTC has held a number of public consultations on the topic of payphones, and it invited consumer and providers to comment on the issue.

The report, Results of the fact-finding process on the role of payphones in the Canadian communications system, clearly shows that the use of payphones by Canadians is decreasing steadily. Compared to 2004, when 50% of Canadians reported occasionally using these services, today only 32% of Canadians report having used a payphone at least once over the course of the year.

Of course, mobile technologies and wireless telephony services rack up much higher numbers these days.

‘Don’t hang up’ on payphones, says Canada’s telecom regulator: they still provide real value.

Yet consumers and consumer lobby groups say that the argument that wireless service is a substitute for payphone service does not fly, particularly for Canadians who are economically disadvantaged, live in under-served areas, or those who simply seek a more affordable, accessible and private phone connection than might otherwise available.

(Some love payphones as they are handy clocks, too, displaying the time of day any time day or night.)

“Although payphones are no longer used as much as in the past, they continue to play an important role in society and serve the public interest,” Jean-Pierre Blais, Chairman of the CRTC, said with the release of the report. “We want to make sure that Canadians are notified when certain payphones are removed in their communities, and that they have the opportunity to share their concerns with local authorities. These authorities will be empowered to respond to the needs of their communities.”

Those communities have fewer and fewer ways to act upon those needs: Canada’s phone providers reported low usage to the CRTC, describing how some 10,000 payphones were taking in less than 50 cents a day. There are some 50,000 payphones in operation in Canada now, the CRTC noted, a number far below the 118,000 units tallied in 2008.

Not surprisingly, and perhaps even causally, major telephone companies have boosted the cost of a payphone call over recent years, with rates going from a quarter to 50 cents in 2007, with more recent industry requests for new payphone regulations asking for the right to again double the rate, up to $1 (pay-by-card rates would go from $1 to $2 under their plan).

Of course, any of those payment options are a far cry from the starting point of payphones in North America; in the 1880s, people actually paid a few cents per call to a live person – public phones were placed in an a office-like setting, and attendants collected coins after a successful call was placed.

Payphones eventually became self-operated, of course, and very popular – over two million units were said to be in operation in North America in 2000.

Now, however, many of those units have been decommissioned and removed from the public common.

So in any challenge, there’s an opportunity. A new industry sector has arisen, and Canadian companies are now offering to install, maintain and operate payphones as a service to others.

WiMacTel Canada of Calgary, for example, says it has been buying up payphone assets for years now and it will continue to do so as a way to further its business model.

WiMacTel payphones, placed on a company’s premises, can earn the host a financial commission on the revenue each payphone generates. That commission applies to all kinds of add-on services, too, not just the basic call, WiMacTel notes as it targets airports, hotels, hospitals, shopping malls, convenience stores and truck stops across the country.

Not just a business opportunity, payphones – or their slow demise – are also presenting a creative opportunity. Filmmakers, bloggers and social media convenors see the romance, nostalgia and changing telephonic landscape as a terrific story to tell, and a powerful metaphor for our times.

Fewer people are using payphones, although many still take shelter in their presence.

-30-