In a unique mash-up of music, science, medicine and technology, professors at the University of Toronto Faculty of Music enthralled a live audience recently with demonstrations of how music can help heal certain medical conditions.

Music was positioned as the next frontier of science and medicine when the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music hosted an event that highlighted recent research efforts using the latest techniques and technologies in wearables, motion tracking, data analysis and more.

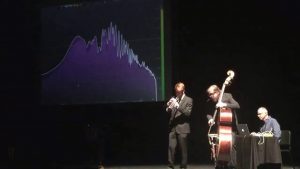

The Sounds of Science: Music, Technology, Medicine presentation at the University’s MacMillan Theatre last May involved not only the faculty, but also performers and artists with whom they work.

In one instance, the audience both listened to a Bach violin sonata and watched as a computer-generated skeleton mirrored the way the violinist was moving her arms, wrists and neck as she played.

The violin she had was a familiar sight; not so much the many accelerometers she had on, strapped around her head, waist, elbows and wrists. The wearable technology tracked her movements electro-mechanically, measuring both static forces such as gravity pulling on her legs and trunk, and dynamic forces like the strength and impact of her bowing technique.

The measurements were then transposed into a computer graphics program, which used the data to bring the skeleton image to life. The sequence was video projected on a large screen behind the performance area (and it is streaming on YouTube).

Wearable tracking and motion detection sensors and motion help researches at the U of T see and analyze the musculoskeletal structure and movement of a violinist in real time, as she performs,

U of T doctoral student Linnea Thacker performed; she is an accomplished musician (playing both as a soloist and in a variety of ensembles, ranging from string quartets and full orchestras to folk and jazz groups), and a recipient of a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship for her research into musculoskeletal disorders in violinists.

After her performance, Dr. John Chong spoke to the many different kinds of injuries high level musicians suffer, often triggered by repetitive motion, and how technology like that worn by the violinist is being used to prevent or treat such injuries.

By measuring muscle and motion activity during a musical performance, he said later, motor control can be correlated to performance impact and outcome. The technology platform used delivers real-time biofeedback and analysis of motion and movement mechanisms.

Orchestral musicians often face muscle-related injuries, Dr. Chong described, and even pop or rock musicians must teach their muscles to hold and play their instruments. Like an athlete training for a race, musicians must practice hard to train their arms, hands, and fingers—and even their lips and tongues—to perform better and faster.

Dr. Chong is also medical director of the Musicians’ Clinics of Canada, working at facilities in Toronto and Hamilton, ON. He and his team specialize in the diagnosis and treatment of occupational injuries suffered by musicians and performers, and his clients have included members of the Hamilton Philharmonic, the Toronto Symphony, the National Arts Centre Orchestra, the Tragically Hip, Our Lady Peace and Blue Rodeo.

Music-related health problems derive from the interface between a musician and his or her instrument, or the musician and his environment, Dr. Chong says, and he uses technology to analyze the ergonomics of that interface — too much force, too many repetitions, too much sound or volume.

Other U of T professors also engaged the audience with their presentations about music and medicine, such as that from Professor Lee Bartel, who showed how musical notes and the vibrations that cause them can be used in treating Alzheimer’s.

Such vibrations stimulate the brain, he described, and help return damaged brains to normal function. He noted that Alzheimer’s and fibromyalgia patients reported decreased pain as soon as three weeks after treatment began.

Jeff Wolpert, head of the new Masters degree program in digital music technology, showed how music could be altered to enhance its effect on the brain, and cardiologist Dr. David Alter described how music could be used in cardiac rehabilitation, using musical frequencies and rhythms to trigger human responses.

Music has always been able to elicit human response, be it emotional or physical. Now, in combination with technology, music is bringing forth medical or biological reactions.

As do many of us, musicians face the risk of repetitive motion strains and injuries; now, tracking technology like this young violinist is wearing can be used to combat such issues.

-30-