When Canada’s broadcast and telecom agency asked for public input about whether the Internet should be regarded as a basic need, well, Canadians responded big time.

More than 65,000 pages of submitted materials were received by the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) during its 2015/16 hearings and consultation period.

Opinions from telecom companies, government agencies, public advocacy groups, non-profit organizations as well as some 3,000 individuals were received, and ultimately posted to the CRTC website.

So far, so good.

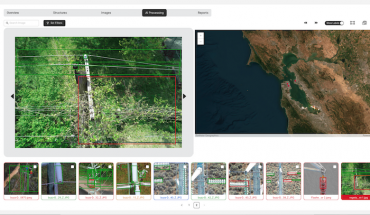

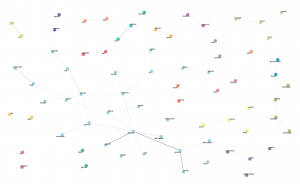

Close-up detail of a bigram plot (full size below) shows frequently used words sent to the CRTC, and analyzed by a new AI tool developed in Canada. A bigram or digram is a sequence of two adjacent elements from a string of tokens, which are typically letters, syllables, or words.

But when researchers or other interested parties tried to access all that information and make some sense of it, they faced at best a cumbersome process. Multiple — sometimes incompatible — document formats had to be bridged; content in non-searchable form had to be located; and comparisons among non-categorized submissions had to be made.

All very difficult tasks. And while the CRTC’s eventual decision (that access to the ‘Net should be a basic right) was well received, it became clear that dealing with the sheer volume of content submitted to a public policy consultation required a whole new kind of data mining tool.

With 65,000+ pages of submissions available, what is the best way to ensure that government decisions are truly based on an accurate reading of public input?

The data science team at Alberta’s not-for-profit technology accelerator, called Cybera, took on that challenge (funding was received from the Canadian Internet Registration Authority’s Community Investment Program).

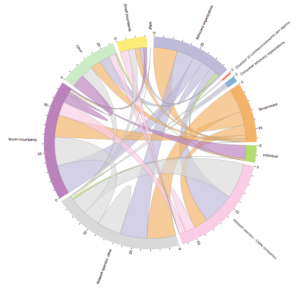

Cybera’s chord diagram tracks questions asked and received by Canada’s telecom regulator during recent hearings about the Internet. It shows relations between who gets asked the most questions, who asks the most questions, and from whom. For example: all of the CRTC’s chords are wide from the start and narrow at the end. The CRTC asked lots of questions, but no one asked the CRTC questions.

The team describes how it had to develop machine learning techniques to pull formatted text and data from a wide range of formats and document (various word docs, spreadsheets, pdfs and more) that preserved both the content itself and the context of the submission overall. Many submissions used conversational English, others were in legalese.

In other words, the team uncovered not just potential differences of opinion but differences of language and intent present in the descriptions of how Canadians use and prioritize the Internet.

Cost is clearly a major factor, and concepts of affordability mean different things to different people (or companies). Large telecoms used phrases like “market demand” and “economic benefits” to make points about affordability; individual Canadians used words like “jobs”, “home” and “food”.

A balanced evaluation of that kind of input would need to take into account the terms used, not just the points being made. Cybera’s new Policy Browser tool helps make that kind of evaluation possible, and it helps researchers get an accurate picture of how public submissions impact, influence or determine regulatory policies and government decisions.

“It’s still early days for the Policy Browser tool and the data analytics it can run. One of our biggest accomplishments so far was making the submissions more accessible,” Barton Satchwill, Vice President of Technology at Cybera, described in a blog post. Referring to those Basic Telecommunications hearings, he recalled how the CRTC made documents available on its website for individual download, but also how cumbersome a process it was, probably taking one person a lifetime to go through them all.

“This will make it easier for researchers to study the role that public submissions play on how regulations and policies are created,” Satchwill added. “Our hope with this platform is that it can be adapted for other government consultations.”

Bigram plot of frequently used words (and how they were associated with other words) in submissions to the 2015 CRTC Basic Telecommunications consultation.

Interest is growing among researchers who want to use the tool to analyze other public consultations held by the CRTC, such as the recent Fairplay consultation, which created a firestorm of criticism against an anti-piracy proposal calling for a new federal agency to help shutdown websites with so-called pirated content. Midway through that consultation, more more than 5,440 responses had been shared with the CRTC.

No matter what the specific consultation or topic of public discussion, Cybera has pulled together different content scraping and text mining techniques that can be used to extract information based on criteria that are both user-identified and machine-learned.

Ideally, it is not just the common phrases and language used in government consultation submissions that are more easily analyzed with such tools, it is the overall intent and impact of public policy-making.

To that end, the data team at Cybera says methods for correcting errors in the data in a traceable, transparent manner could be added to the toolset, which will be adaptable to navigating other public consultations and forms of policy documentation.

Cybera built the Policy Browser using open source tools, and is making the source code available to anyone who would like to apply it to other data mining applications involving large numbers of text files.

Cybera built the Policy Browser using open source tools, and is making the source code available to anyone who would like to apply it to other data mining applications involving large numbers of text files.

-30-