We give up our friends. Our photos. Our faces. We even give away that most important form of human-generated data – our genes.

We get in return some comfort and convenience – that enhanced user experience, those so-called free services, those apparent insights into our personal future and family history.

We think we are consumers, but in fact we are producers. It is our content, our data, that creates value in today’s digital economy.

We are called users, but in fact we are unpaid workers: we create new revenue streams for multi-billion dollar companies with every click we make.

The results of all our labour: giant pools of digital information about us that are bought and sold and analyzed and packaged in order to generate corporate profits, if not influence public attitudes.

Often without our knowledge.

For years, we’ve been giving our data away to companies like Facebook and Google, Instagram and Twitter, seemingly with little regard for– or awareness of – the possible consequences.

Millions and millions of people are giving away their face – to be used by facial recognition and face-aging apps.

Facial aging apps are just the latest example; genetic testing kits may be the most concerning.

Reports indicate that more than 150 million people have clicked on the FaceApp offering, in order to see what they may look like years from now. It’s not a new app, and concerns about it and other face-aging apps like it are not new, either.

Some users are placated with statements by the company about its data privacy and storage policies, yet its own user agreement leaves the door wide open for a range of data uses as yet unknown:

You grant FaceApp a perpetual, irrevocable, nonexclusive, royalty-free, worldwide, fully-paid, transferable sub-licensable license to use, reproduce, modify, adapt, publish, translate, create derivative works from, distribute, publicly perform and display your User Content and any name, username or likeness provided in connection with your User Content in all media formats and channels now known or later developed, without compensation to you.

Pretty all-encompassing, isn’t it? Yet that policy is not that much different from other privacy policies or terms of usage statements found on many social media platforms and content sharing sites.

While user agreements and privacy policies are difficult reads at best, at least they are available.

There are reports that folks in the U.S. are being approached on the street and asked for a snapshot of their face, in return for $5 (the worker gets paid, after all).

It seems Google employees are stopping people in the street and giving them gift cards in exchange for their face data, explaining only that it’s for a future Google product.

The downside of giving it away here is not so much that someone may master the difficult technical trick of mapping a flat two-dimensional image onto a three-dimensional model in order to create a realistic online (but nevertheless fake) person, or using such photos to unlock iPhones.

It is at the very least an unfair economic exchange in which the true value of what is being given is not recognized nor reciprocated. It some situations, that inequity is called economic exploitation.

Or worse.

A privacy lawsuit against Facebook over the collection of users’ biometric data may proceed, a U.S. federal appeals court has ruled. It is alleged in the suit that Facebook’s collection and tagging of photos violated state law. Facebook denies the allegations and is contesting the lawsuit.

The genetic testing market is predicted to triple in size in the next few years, reaching $300 million by 2022. FirstStepDX Genetic Test Kit Package by Brian Glissmeyer licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 .

Photos and faces are one thing, but the risks are more apparent in the increasingly popular trend of giving away DNA.

The genetic testing market is predicted to triple in size in the next few years, reaching $300 million by 2022. Yes, being able to ascertain apparent insights into our familial history is attractive to many, but one of the main reasons for the market growth according to some analysts is a lack of government regulation.

Or is that a whack of government interest?

There’s a great deal of interest in genetic information from the insurance sector, from big pharma, from law enforcement and yes, government agencies.

Reports that a major DNA home testing kit provider had given millions of its customer profiles over to the F.B.I. (without notification of such a possibility) points out just one way genetic data might be used that isn’t about tracing family roots.

The user agreement at another DNA analysis firm opens the door wide: it states that users (those who give up a sample of their genetic code) grant to the company “a royalty-free, worldwide, sub-licensable, transferable license to host, transfer, process, analyze, distribute, and communicate your Genetic Information for the purposes of providing you products and services.”

Those giving away their DNA to such testing firms will also be asked to provide even more data: one testing firm asks for self-reported content about medical and family history, personal traits and ethnicity, illnesses or diseases suffered.

Some users build online profiles about themselves and their genetic data, and they may upload text, pictures, videos and messages – all of which will be available to the testing company (which also conducts fairly standard web tracking activities such as storing IP addresses, browser preferences, click tracks and page visits).

All of this is covered in a lengthy privacy policy that ends with the note that “additional ‘just-in-time’ disclosures or additional information about the data collection, use and sharing practices” may be added. Corporate mergers and take-overs can also impact the privacy policy of genetic testing companies, as was revealed in reports about international pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline and genetic testing firm 23andMe.

A swab of saliva from inside the mouth is all that’s needed. Image use GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 Richard Wheeler (Zephyris) .

Growing privacy concerns also surround the genetic testing sector: reports, such as of a data breach at a genetic testing company where a large number of accounts were hacked, as well as at a third-party financial and accounting firm associated with one of the genetic testers, are increasing.

In Canada, it is a particular concern that none of the major privacy laws here (not PIPEDA, the nation’s privacy act; not ARPPI, the Quebec private sector privacy law; not PHIPA, Ontario’s health data protection statute) specifically refer to genetic material as personal information, and therefore the protections those laws offer are not applicable – yet.

As group calling itself the Canadian Coalition for Genetic Fairness may be able to help.

It says all Canadians are at risk from the availability of genetic information about them. It wants to help industry, government and the public explore policy options aimed at mitigating, preventing or prohibiting the use of genetic information in inappropriate ways, such as assessments and decisions related to employment and insurance.

The Coalition points out that Canada’s 2017 Genetic Non-Discrimination Act does prohibit the collection, use, and disclosure of an individual’s genetic test results without their written consent. Fines of up to a million dollars or imprisonment for five years could result.

That’s a lot to give up – but it hardly seems to balance out with the value of our friends, our faces or our genetic identity.

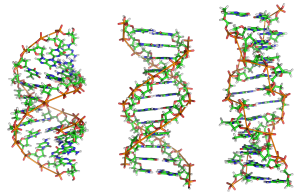

DNA’s double helix structure, clearly visible in these A-DNA, B-DNA and Z-DNA samples, helps carry and convey instructions for the development, function, growth and reproduction of all known life forms: Image courtesy: Mauroesguerroto, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

-30-

Face-swapping apps are a big deal in China it seems, and the need for personal amusement and distraction are alive and well.

Personal privacy protection not so much.

Zao and Yanji are both on the Top Five download charts at China’s iOS store. The apps let users give away images of their face, with the idea that the have fun placing their own facial image onto that of a famous celebrity, like a move star or TV hero. Animated GIFs or even video clips can also be uploaded to ‘add’ to the ‘realism’ of the ‘deep fake videos’.

But reports indicate that the user agreement for the Zao app says the developer gets “free, irrevocable, permanent, transferable, and relicense-able” rights to all user-generated content. Zao may have updated its policy to more equitable terms since product launch, but in addition to the developer’s standard ‘we’ll improve your user experience’ pledge with all the data we gather, the privacy agreement still mentions other uses for the freely-given-away personal data that’s ‘pre-agreed to by users’.

Frowning face emoji placed here…

Data generated by individuals creates wealth and individuals have the right to directly receive any profits generated from their data! Similar to copyright. Individuals should have the option to opt out of any data collected !