You were probably surprised (or something) to get any message that early on a Sunday morning, much less one about a nuclear incident.

The surprise is justified – it was, in fact, the first time the cross-country emergency system known as Alert Ready was used to send out a nuclear-related message.

Missing children, sure. Severe weather, OK, those kinds of alerts are at least somewhat familiar.

Not long after we received the first-ever nuclear-related alert, we got the first correction.

But a warning about a possible nuclear emergency? That’s just one of the surprises revealed about our country’s alert system.

Last year, Ontario had 49 emergency system alerts – 16 Amber (missing children) Alerts and 33 severe weather notices, mostly about tornadoes. Canada, overall, had a total of 131. None were about nukes.

So not only did we get the first nuclear-related alert splashed across our screens, soon after we got the first correction.

The message about an incident at the Pickering Nuclear Generating Station, just east of Toronto, was issued mistakenly early on January 12. Later that same day, an investigation was announced to look at why the alert was issued, where the error was introduced, how to prevent future incidents and how to maintain public trust in the emergency alert process.

“The alert was issued in error to the public during a routine training exercise being conducted by the Provincial Emergency Operations Centre,” tweeted Ontario’s solicitor general, Sylvia Jones, in a statement at the time.

“The Government of Ontario sincerely apologized for raising public concern and has begun a full investigation to determine how this error happened and will take the appropriate steps to ensure this doesn’t happen again.”

That report has just now been released by the solicitor general.

The emergency alert was issued as a result of human error, the report says, adding that systemic issues also contributed to both transmitting the alert and delaying the correction.

The report calls for enhanced training for alert system operators and a new two-person authentication protocol for issuing alerts as part of its recommended corrective actions. Further investigation is called for, but the report does not substantively tackle issues about geographic distribution, platform compatibility, rural/urban coverage, nor the actual clarity or ease of comprehension of the text-based messages themselves.

Clarity of Message

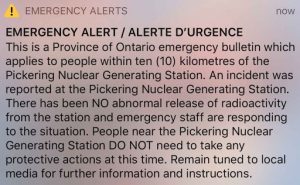

Even to the clear-eyed and wide awake, the content of that first nuclear message was confusing, perhaps contradictory. Buried eight lines deep in the screen-filling text-based message it finally says “NO protective actions needed”. Phew! Glad I was alerted to do nothing.

It’s a tough read anyway, but first thing on a Sunday morning a dense text message may be even harder to decipher and respond to. Supplied image.

But it starts by shouting “EMERGENCY ALERT”, follows up with phrases like “emergency bulletin” and “incident reported” only to then state that there’s “NO abnormal release of radioactivity”.

(There are, you may be surprised to hear, normal releases of radioactivity.)

The Sunday morning alert also noted “emergency staff are responding to the situation” perhaps as reassurance, but also opening the door to as many questions as answers. No radioactivity released, no protective action needed, but still an emergency team, a “situation” and an alert.

Geographic Proximity

As has happened before with emergency alerts in this country, the geographic targeting of such messages needs to be addressed, as well.

The Pickering alert was intended for people within a 10-kilometre radius of the facility; nevertheless, people more than 50 clicks away got the message. That apparent lack of technical focus echoes concerns of people who have received Amber Alerts in Toronto about missing children in Timmins.

In fact, issues with the emergency management system here were previously cited in another provincial report, one that concluded our programs needed both better oversight and coordination.

(The Pickering nuclear plant itself has been the subject of critical reports: it was due to be decommissioned this year, but current and former provincial governments have decided to keep it open until at least 2028. Perhaps that news should have been shared in an emergency message.)

Platform Compatibility

There is a technical as well as a procedural underpinning for the emergency alert system in this country. A wireless device that is compatible with the public alerting system must be an LTE device; that’s an older standard based on 3G predecessors; it’s not quite 4G and not yet 5G. Since April 2019, all new phones sold in Canada are alert compatible.

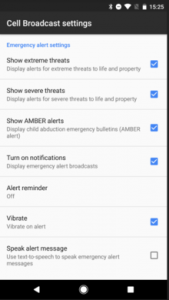

Different devices and smartphone settings may respond in different ways to alert messages. The Cell Broadcast System, shown here on Android 7.1, underpins the delivery of the alerts. Creative Commons image CC BY-SA 4.0.

The device also must be pre-loaded with special software. For some, that was another surprise: my phone is loaded with communication software I knew nothing about. Did I consent?

The software enables what’s known as the Cell Broadcast System, on which messages are sent to an entire transmission cell or area of coverage, not just a specific phone. The system can reach thousands of cells and therefore millions of mobile subscribers in just seconds.

It’s an unconfirmed push service, meaning the number of cells it reaches can be checked, but not the individual recipient. While the alerts may look like text messages, they are not text messages and are not billed like text messages. The system is not affected by the access or SIM class of the device, it does not require subscriber identity or device ID numbers.

That’s one way to try and reassure people that the alert system will not and cannot collect data about them, their device or their location. That’s good if privacy is a concern.

But it also means the alert issuer cannot specifically measure how many people actually receive the emergency alert messages. That’s bad, in that any evaluation of the efficacy of the system might want to take into account its actual reach and recipient reaction.

Recipient Surprise

How do you react to an emergency message on your phone? What did you do that Sunday morning?

A friend of mine said she looked, groaned, rolled over and went back to sleep. A neighbour, who actually used to work for Ontario’s nuclear agency, said he had a much stronger reaction to the message (which was barely placated by the retraction later that day) knowing how serious a nuclear situation could be. Some folks react with unwarranted anger and criticism when they get a seemingly irrelevant Amber Alert: while the message’s geographic focus may be poor, the underlying intention is good.

But you’re actually supposed to react in a very specific manner, as alert system officials describe: “When an alert is heard, it is the responsibility of the public to stop, listen and respond as directed by the Government Issuer.”

But you’re actually supposed to react in a very specific manner, as alert system officials describe: “When an alert is heard, it is the responsibility of the public to stop, listen and respond as directed by the Government Issuer.”

But a compatible wireless device that is turned off will not receive an emergency alert. When the device is turned back on, if the alert is still active for the area, then the alert should be displayed. A device set to silent will not normally notify the user about an incoming alert, but depending on the actual unit, the sound may override user settings.

(It’s even harder for some folks to respond to a message: certain rural areas of the country are known to be poorly served or covered by cellular signals: the so-called digital divide means that just based on where you live, you may not get emergency alerts.)

Connecting Emergency Alerts and Weather Predictions

Despite the shortcomings, despite the complaints, despite the government reports calling for an enhanced alert system, we do have a national system to deliver important information to as many citizens as possible, using as many technology platforms as available or appropriate.

The public-facing side of the system, Alert Ready, sits on what is known in the industry as the National Alert Aggregation and Dissemination System, or NAAD.

It takes alert information from a Government Issuer (any one of a number of agencies, from Environment Canada to Ontario Power Generation, among others) and pushes it to Alert Distributors (television, radio, cable, satellite and wireless companies) using satellite and Internet feeds.

NAAD is owned and operated by Pelmorex Corp., the parent company to the TV channels The Weather Network and MétéoMédia. The fact that a private company, rather than a government agency or third-party not-for-profit organization, runs the emergency system is a surprise to many.

Pelmorex is not only licensed to do so, but it also has a strong technical experience that makes it the appropriate one to do so.

The weather services Pelmorex operates have long been able to deliver information to specific areas and to piggy-back that information on existing delivery channels. Pelmorex can target very specific regions with its weather forecasts by “tagging” its content with a kind of technical postal code that tells delivery platforms where to show the relevant content. Pelmorex does not charge end user consumers for the alert service; as part of the licence to operate its weather channels, the company can charge wholesale rates to carrier platforms like cable TV operators that are set in part by the agreement to distribute alerts. Its weather channels get preferred placement on a cable system’s lower tier; that means wider distribution for the channel and greater access for the public to any alerts it may carry.

Pelmorex first proposed a national alert system nearly twenty years ago; what was called the All Channel Alert system has grown and evolved since then.

Based on the findings of the government’s report about that Sunday morning alert and the surprise it generated among some recipients, it’s easy to say there should be more growth and evolution to come.

# # #

Emergencies are no laughing matter. Alerts are serious business and should always be heeded in the most appropriate manner. But….

Whenever I hear the word “emergency” I just cannot get out of my head an absolutely hilarious scene from an absolutely fantastic old movie called The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming!

(Thanks to, among others, Carl Reiner, Alan Arkin and the great Toronto-born director Norman Jewison for this classic. It concocts a story about some Russian submarine sailors, accidentally stranded on a small island off the New England coast. In a misplaced attempt to conceal the situation, the sailors try and warn island residents about an “emergency.”)

I urge you to watch the entire film; the animated gif below and most clips online barely do it justice.

-30-