Baseball season’s back for 2020, and big changes are on deck for the sport and the people who play it: big data, adaptive technologies and, yes, new rules and new rule-breakers are now part of the grand old game.

On the bright side, technology is being developed to enable those who cannot now play baseball, due to a physical or sensorial limitation, to enjoy the sport as active participants.

Leading companies like Microsoft are among those developing the technological underpinnings for what are called sensory-substitution devices, or SSDs – gadgets that, for example, let visually challenged people “see” by converting and reinterpreting what they hear.

Unfortunately, however, technology has also been used to enable those who can now play the game to cheat at it.

The repercussions of the sign-stealing scandal that’s currently rocking Major League Baseball have yet to subside: what’s clear at this point is that technology has already enabled the Houston Astros, Boston Red Sox and perhaps other teams to gain an unfair advantage over their opponents.

Video cameras, software apps, computer algorithms, even garbage can lids were all reportedly part of a sophisticated system used by the Astros to observe, document, decode and relay an opposing team’s pitching decisions to their hitters – while at bat!

The so-called “Codebreaker” system was allegedly introduced to then-Astros general manager Jeff Luhnow in 2016. That led to the 2017 lid-banging system, which in turn led to the suspension and firing of Luhnow and the team manager. Other firings have, and may still, come as a result of the scandal.

(TIME OUT CALLED:)

Luhnow is among many other top executives at many other businesses who are enamoured with what big data analysis promises to do for their team, their business, their industry. Get me enough data, and I’ll have the solution to pretty much any issue. I’ll have an advantage over pretty much any competitor. It’s a risky infatuation that can bring unintended consequences in many arenas, not just sports.

Back in 2012, Luhnow described his vision of how technology brings benefit to his particular field of dreams: “It’s an issue of collecting and evaluating and interpreting and using information across a whole bunch of disciplines… And if we can do that five percent better than the rest of the clubs, that’s a significant edge.”

MLB player Mike Fiers, seen here pitching for the Houston Astros in 2016, is called the whistleblower who brought baseball’s current sign-stealing scandal to light. Creative Commons image. Arturo Pardavila III (Original version posted to Flickr as “Mike Fiers pitches vs. Yankees”) Cropped by Ucinternational. CC BY 2.0.

Cheerleading for that significant edge has been dampened by what’s now transpired. Big data analytics may well bring advantages, but they must be implemented in the context of fairness, integrity, legality. Before the team’s fall, leading corporate consultants and strategic advisors were celebrating the Astros in articles with titles like How the Houston Astros are winning through advanced analytics. Yes, Houston won the World Series, but the team has lost standing big time in the eyes of many baseball fans.

That article, by the way, has since been pulled from the game and removed from the website of international consulting firm McKinsey & Company, where Luhnow and other once celebrated, now-controversial figures once worked.

(BACK TO THE ACTION:)

So rather than giving an unfair advantage while playing a game, technology can be used to ensure folks can play at all.

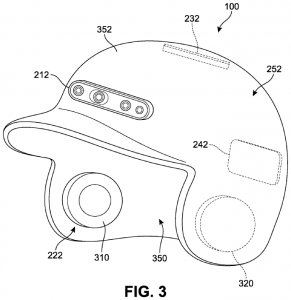

Microsoft describes how depth sensors, embedded in a baseball helmet, could detect and translate distance and direction information into sounds.

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, who’s at least partly motivated by experiences with his disabled son, continues to push his company’s adaptive technology efforts so people with disabilities can work, live and play on a levelled playing field – and the baseball diamond.

Microsoft’s Azure system, Kinect smart sensors and Xbox adaptive controller platform have already been integrated into various other industrial applications and consumer products.

The Azure Kinect Developer’s Kit includes AI sensors with sophisticated computer vision and speech capabilities, an advanced depth sensor and a spatial microphone array with a high-res video camera and orientation sensor, an accelerometer and a gyroscope (IMU) for sensor orientation and spatial tracking, and other synchronizing and sensing features.

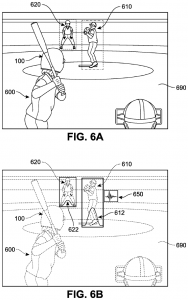

Recently, a patent was published in which Microsoft describes how depth sensors, embedded in a baseball helmet, could detect and translate distance and direction information into sounds. The speed and direction of a baseball would be conveyed to a player through “sensory substitution” and the technologically enabled conversion of visual information into audible signals.

“Objects in the real-world are observed by a depth camera and classified,” according to a Microsoft tech patent. “The classification is used to identify a sound corresponding to the object.”

In its “method for providing auditory sensory substitution using an assistive device”, the patent describes how “[o]bjects in the real-world are observed by a depth camera and classified. The classification is used to identify a sound corresponding to the object. The device is configured to permit vision-impaired players to participate in athletic events.”

The idea seems a bit fantastic at first (MLB pitches travel just 60 feet or so, but they can do so at speeds over 100 miles per hour), and Microsoft acknowledges that the device described in its patent “does not necessarily have to be on the shelves”.

But there is an overall commitment to developing inclusive technology and sensory substitution devices, and not just at Microsoft. And not only for baseball.

Researchers have presented a paper at the University of Geneva in which a sensory substitution platform called See ColOr is used to enable blind individuals to play tennis based on sound-based spatial perception information. The sounds can be musical, and triggered by not only data from perceived depth but also object colour.

While a smart dedicated baseball helmet with sensory substitution and other smart tech capabilities may not even make it to first base, there are some unique entrants in the tech-enabled headgear game looking to score now:

The geodesic plywood helmet developed by American artist and engineer Jordan Reynolds takes the SSD idea to the other side – it is both a sensory deprivation and an over-stimulation device. Sounds, visuals and other sensory stimulants can be delivered into the helmet’s internal space using an array of technology and media gadgetry. It’s not great for sports, but handy if you want to desensitize and cognitively dissociate people from the reality around them. Hmmmm…..

A crowdfunding campaign for the Jarvish Smart Helmet seeks a market for tech-enabled headgear. The X-Series includes built-in HD surrounding sound speakers, noise reduction microphone and front 2K camera as standard. Integration with Alexa AI, Siri and other voice-enabled platforms is also featured. The X-AR also includes a 2K rear-facing camera and optical waveguide technology, along with augmented reality (AR) projections on the inside. Geez, that could really help someone follow a pitched baseball.

As Reynolds’ headgear intends, and as the Jarvish helmet intimates, there can be risks associated with SSDs: one of the identified dangers for people using a sensory substitution device is TMI – too much information.

We all have a limit to our attention capacity. Sensory overload of pretty much any kind (big data included) can have negative consequences that impede our ability to focus on important signals and key information. SSDs need to be very task-oriented to avoid such overload, and of course, they need to be comfortable, convenient and easy to use.

Mobility and even appearance are also key factors in developing and ultimately adopting SSDs, researchers say. On the sports field, speed and style have long been part of a winning strategy.

-30-