COVID Alert, the new mobile app developed to help notify Canadians if they’ve been exposed to someone who tested positive for COVID-19, has been downloaded more than 1.3 million times since its official release on July 31. There are an estimated 31 million smartphone users in Canada.

They can now get the app as a free download to compatible smartphones (those made in the past five years) running a relatively new operating system (at least Apple iOS 13.5 or Android 6.0). The app had been delayed for more than a month following the first announcement about its features and functions. A short ‘beta test’ of the app was conducted the weekend prior to its release.

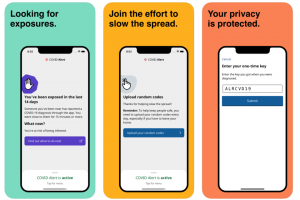

The app’s design is said to focus on privacy — the need to protect personal private information and medical confidentiality. While gaining the user community’s trust is crucial for the app to meet its goals, the medical community may feel the app is less than completely useful.

Use of the COVID Alert app is entirely voluntary: the download, initialization, use of, and response to the app are all up to the user. He or she decides whether to share a COVID-19 positive test result. He or she user must consent to exposure notification to use the Bluetooth signals. Users can turn off the app at any time. And, if notified of contact with a positive COVID-19 case, users must then decide for themselves what action to take in response.

In these early days, the app continues to show what it does and does not do.

What It Does

As a tool to help contain the spread of the coronavirus, the app makes use of a compatible phone’s Bluetooth signal capabilities to ping or handshake other nearby smartphones running the same app. Those pings are identified by an anonymous random code. The app keeps a record of those coded handshakes, so if one of the users later tests positive for COVID-19 and chooses to let the system know about it, the pinged contacts he or she has had in the past 15 days are notified that they may be infected themselves. They are advised by on-screen app notifications about the next steps, such as possible quarantine, monitoring symptoms, contacting a health care provider, getting tested, and, if necessary, self-isolating.

(To state the obvious, people who are showing symptoms and signs of the disease and have tested positive for COVID-19 should not be out and about; they should be in isolation. Those who have had contact with a positive case should monitor themselves carefully for any symptoms, get tested when and where possible, and be prepared to self-quarantine. Because people can be contagious and spread the disease to others even before signs or symptoms show, contact notification apps may not be helpful; getting tested and following up-to-date health care information are key steps in any case.)

Developers say (and much of the code is publicly available) that the app uses strong measures to protect any data it collects and does not track a user’s location or collect personally identifiable information. While a patient’s health care practitioner will certainly know who the person is, the app does not know who the positive case is and it does not know who possible contacts may be. All data sent and received by the app are de-identified and anonymized, so there is no obvious record of who has tested positive and where the contact(s) occurred.

While it has not been confirmed in government announcements, it is known that the government uses servers owned and operated by Amazon, but based here in Canada.

The Privacy Commissioners of Canada and Ontario were consulted on the development of COVID Alert to assess its level of privacy for Canadians using the app.

“We’re taking every step necessary to ensure Canadians have the confidence and trust that their data is being protected,” said Canada’s Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry, Navdeep Bains, when the app was released.

They say it is good to go.

What It Doesn’t Do

Although those privacy commissioners say the app itself doesn’t raise privacy concerns, the inadequacy of Canada’s privacy laws is a concern that the app uncovers, but can do little about on its own.

A statement from the federal Office of the Privacy Commissioner notes that the app does not collect personal information, but the OPC goes on to point out that the federal Privacy Act does not apply to this contact notification initiative.

“(I)t bears noting that an app, described worldwide as extremely privacy sensitive and the subject of reasoned concern for the future of democratic values, is defended by the Government of Canada as not subject to its privacy laws,” the OPC’s review report notes. “This is again cause for modernizing our laws so that they effectively protect Canadian citizens.”

In a statement received from the Ontario Ministry of Health, WhatsYourTech.ca was also informed that “the app doesn’t collect or share any personal information, such as the name, phone number, permanent device identifiers, locations, or health status of any user.”

But, in a query that many privacy advocates thought they would never hear, the question nevertheless presents itself: are we too private? Much of that information could be very useful to health care providers.

In the context of a pandemic, from a public health point of view, it is “an interesting place to be.”

That’s the description of the delicate balancing act between personal privacy and medical efficacy that app developers face; the concern was voiced during a fascinating event held last month by the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) which featured Apple’s Senior Director of Global Privacy Law and Policy Jane Horvath, and Google’s Chief Privacy Officer Keith Enright.

Apple and Google of course are key development partners of the CNS (contact notification system); it is their platforms on which such apps run and their participation in the development process was (and still is) a crucial element of success.

Apple and Google of course are key development partners of the CNS (contact notification system); it is their platforms on which such apps run and their participation in the development process was (and still is) a crucial element of success.

(COVID Alert’s development is described as a collaboration among Health Canada, the Canadian Digital Service, the Province of Ontario, and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, building on an exposure notification solution developed by Shopify volunteers in coordination with the nonprofit Linux Foundation Public Health.)

But in the IAPP keynote entitled ‘The Platforms Weigh In: Privacy, Exposure Notification and Contact Tracing’, the Apple and Google tech execs accurately noted that they are not epidemiologists, not virology specialists, not researchers at a leading medical school.

The care with which privacy is protected in the app brings a downside in this instance: there’s a noticeable lack of actionable data that can be used by health care professionals, medical and scientific researchers, and, yes, even businesses and governments, to learn more about the spread of the disease.

Robust, accurate, and up-to-date data are needed to help determine how the virus is spread, where it is spreading, who is spreading it, what containment measures are successful, and what measures need fine-tuning in order to help contain the virus and reduce cases of the disease.

(A key point to make about the app is that it is just one of a number of tools available to fight the pandemic: if this app does not ask a COVID-19 case or contact where they were or who they saw, well, a good contact tracing program will. Such information is crucial in combating contagious diseases; the app is but a newly developed contact notification tool; contact tracing is a long-standing medical technique to fight pandemics.)

Although technical adjustments may be coming, the app does not correct an inherent weakness in Bluetooth signal strength – at 2.4 GHz, the reach of such signals can be affected by physical obstacles and interference, including metal objects, human bodies, or other devices that emit strong RF signals.

There will be an audit of the app by the OPC after it’s been up and running for a while; however, no specific details or timelines were announced. An App Advisory Council has also been named to help inform the implementation of the app.

As mentioned, widespread adoption of the app is essential for it to work well (some have estimated that it will require as many as 80 per cent of all Canadians to use it). The fact that the app needs relatively new and up-to-date hardware and software may also limit its uptake by users.

Not all Canadians have a compatible smartphone (many don’t have smartphones at all) and the app won’t help them. Brenda McPhail, director of privacy, technology, and surveillance for the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, said in a statement that the download requirements present an “obvious” issue.

“People who can’t afford the latest technology are unable to download and use the COVID Alert app, but data shows that COVID-19 is disproportionately impacting neighborhoods where incomes are low and unemployment is high,” she said. McPhail is one of the members of the COVID-19 Exposure Notification App Advisory Council.

What We Can All Do

No matter what the app can or cannot do, no matter who uses it or not, there are still important steps we can all take in the fight against the coronavirus and COVID-19, as described by Ontario Health:

Continue to practice physical distancing with anyone outside your social circle.

Wear a face covering when physical distancing is a challenge.

Wash your hands with soap and water, thoroughly and often.

Cough and sneeze into your sleeve or a tissue.

Keep surfaces clean and disinfected.

If someone receives a positive test result, they are advised to self-isolate for 14 days from symptom onset, or, if asymptomatic, from the date of a positive test result. Individuals who test positive will be contacted by their local public health unit, which will provide the appropriate guidance and undertake a comprehensive case investigation to determine how the individual may have acquired COVID-19 and to identify any close contacts who may have been exposed.

Users who receive an alert that they may have been exposed should follow public health advice, including self-isolation.

-30-

nice post