If there’s too much sugar in that can of pop, will you stop drinking it?

If there’s too much data collected by that app, will you still download it?

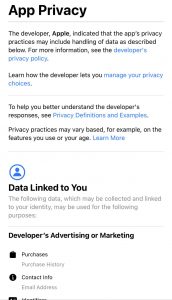

Another daily dilemma for us to deal with: all the apps available through the Apple App Store now have to have a privacy nutrition label, that is, a full listing of the impacts your use of the app can have on your data privacy. So we have to decide if that’s good for us or not.

Like the label that tells us how much fat, how much sugar, how many calories are in that food item we’re about to eat, the privacy label tells us what kind of information is collected by the app, who makes use of that collected data and how, and how data remain linked to a person’s profile even after app usage.

Like many food labels, however, will the data label become so much wallpaper, ignored by the purchaser? Will the purchaser understand the details of what the label conveys? Will he or she act upon that understanding in a way that protects them (and by extension the rest of the online community) from data harm? In many ways, that is is up to us

By requiring and then presenting information about an app’s data collection activities, Apple is giving us tools to protect our personally identifying information online, to understand how that information is used by others, and to inform our ability to give or withhold consent.

The labels will be posted to the app’s page in the store, along with other descriptions of the app’s features and functions.

Again, just like the labels on food in the grocery store, the information on these new privacy labels is only useful if it is read, understood and acted upon.

But unlike the food labels in the grocery store (the contents of which are defined and monitored by the government and Health Canada), the Apple privacy labels contain self-reported information submitted by the app developers themselves.

Apple says that app developers must keep their labels up-to-date and they will be required to disclose, using an online questionnaire, all the information they and their third-party partners collect through their app. Both new and existing apps must have the label (it is actually created by Apple, based on the info provided) and that’s in addition to an already-required long-form privacy policy.

Apple says that app developers must keep their labels up-to-date and they will be required to disclose, using an online questionnaire, all the information they and their third-party partners collect through their app. Both new and existing apps must have the label (it is actually created by Apple, based on the info provided) and that’s in addition to an already-required long-form privacy policy.

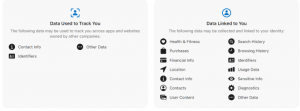

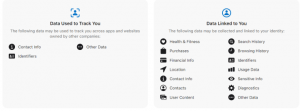

The new labels are divided into sections, variously titled “Data Used to Track You”, “Data Linked to You” or “Data Not Linked to You”. By clicking on one of the titled sections, more specific details are shown, such as collected data being sub-divided into its own usage categories; there are six such categories, one being a rather disconcerting data use: “other purposes”.

Of course, specific actionable information about how our data is used (be it for tracking our website travels; detailing the time spent on certain websites; listing purchases we’ve made or products we’ve checked out; making recommendations to us about possibly related products or services; determining our current physical location, geographic home-base and routes taken between the two, and much, much more) should always be available to us.

It always should have been available.

The privacy facts now provided on the labels will be useful for people to know about and make use of, when and where possible. But the apps will collect all the data they are built to collect and they will share the data everywhere they were meant to share it: the privacy policy will not change that. So it is up to the individual to decide whether or not to download and use a particular app, informed as they are by the information presented on these new data privacy nutrition labels.

Actually, the data label idea is not all that new: at least ten years ago, researcher at the Carnegie Mellon University CyLab in Pittsburgh, PA were working on a “privacy nutrition label” designed to make privacy policies easier to understand and compare. There’s an online demo of the lab’s Privacy Finder software, which although ten years old now is still described as “a work in progress”.

For sure, many privacy policies and online terms of use are interminable, written by lawyers and not for consumers. Clear intent and plain language are certainly needed, and there’s every reason to require privacy policies be more user-friendly and easy to understand. Luckily for us, there’s an app for that, too! If we can’t bring our own time, energy or smarts to the task, we can now bring AI to bear, using a new artificial intelligence tool called Polisis, to read, review and assess various elements of a privacy policy.

Nor do privacy statements really have to be only text all the time. There are some clever ways to present data usage policies in a visually attractive graphic format. Likewise, the privacy policy should not be buried in a website, or only accessed after scrolling and clicking and scrolling some more: there’s every reason to have the privacy policy pop-up first on your screen, before you can do anything.

No one should be disinclined or unable to commit, control, protect and set boundaries for their own life (be it offline or on). But, as has been proposed here before, maintaining personal data privacy online takes some work by all concerned.

Some may be unwilling to do that work, however. App developers are pushing back against Apple’s label, even though resistance seems futile.

Facebook for example says it disagrees with the privacy feature but it has basically has no real market choice in the matter, because Apple can remove apps from its store if the app developers do not comply with the privacy feature and label requirements, such as requiring all apps that want to track users across different apps and websites to obtain their users’ explicit permission. As Craig Federighi, senior vice president of software engineering at Apple, told a European Data Protection and Privacy Conference, “[D]evelopers who fail to meet that standard can have their apps taken down from the App Store.”

In a separate announcement, Apple said that consumers spent $1.8 billion USD at the App Store during the last week of 2020.

In a separate announcement, Apple said that consumers spent $1.8 billion USD at the App Store during the last week of 2020.

* * *

As has been noted here before, consumer awareness, increased education, and provider transparency are crucial.

To that end, what if our favourite gadget or online service came with an info sheet that specifies not just data usage, but the good and the bad outcomes product usage may bring?

How about a owner’s manual that carefully describes the moral reckonings made by the developer and manufacturer before releasing their product?

We’re all used to reading product tech specs about processor speeds, screen resolutions, and bandwidth capabilities. How about specs detailing a social media company’s internal security protocols? Or a list of its work with third-party data aggregators?

Shouldn’t tech specs detail how the ethical obligations a product or service provider has to the consumer, to society, to the planet are being met?

Shouldn’t we all be screaming “Yes!” about now?

Some already are. Tech industry initiatives like Tech for Good, the Center for Humane Technology, Truth About Tech are looking at ways to mitigate the dilemma we’re all facing.

The more the tech manufacturing and marketing community joins in the crusade, the better.

-30-

Great Information. I Just install The Apps And Never Think Like This About The Policies And All, But Now I See Every Information In detail About The App.