Employee monitoring and workplace surveillance means big business. It may also mean big brother.

Employee monitoring lets organizations track the activities of employees and gather information that helps drive productivity and boost security. With an uptick in the number of employees working from home, workers may be subjected to more monitoring and tracking than ever before, often without their knowledge.

Remote monitoring software can capture computer keystrokes and screengrabs, turn on webcams and other device accessories – no matter where they are – in order to monitor employee computer activity. Workplace productivity applications, loaded onto smartphones or other computing devices, can track and even predict worker movements, be they in a warehouse, office tower or cross-country delivery route.

Canadian employers are monitoring employees in several ways, according to a survey conducted by a key product and service provider in the industry: emails (45 per cent), followed by web browsing (42 per cent), collaboration tools (42 per cent), keylogger software (22 per cent), video surveillance (21 per cent) and webcams (20 per cent) are used.

Privacy experts have been warning about the use of workplace surveillance since at least 2004. “(Feckless) Workplace Surveillance” by SebValenz is marked with CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

And while the work-from-home trend brought about by the COVID-19 contagion has surely driven up the amount and nature of employee monitoring, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada has been cautioning about the use of workplace surveillance since at least 2004.

Watching the Growth of an Industry

Now, in a timely update to its nearly two decades-old warning, the Privacy Commissioner’s office has underscored its position, pointing out in a recent speech to the Standing Committee on Social Policy of the Legislative Assembly that the workplace monitoring industry will continue to grow and hit an expected $38 billion in revenue by 2027.

With many industry players seeing such rewarding opportunities, the Commissioner noted in prepared remarks that it’s “easy to see the potential for electronic monitoring tools to get predictions wrong or just go too far, particularly now that the workplace can extend to the home or wherever the employee happens to be.”

Teramind, InterGuard and ActivTrak. Prodoscore, Microsoft, Kickidler, Ekran and ActivTrak. Hubstaff, Veriato 360, Monitask, and InterGuard are among the many companies providing workplace surveillance tools and related services in the growing sector, often called employee monitoring, remote computer monitoring, even agency monitoring.

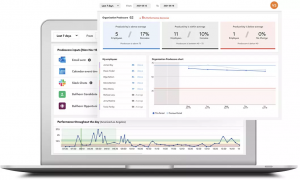

Productivity intelligence will become a necessity in every business, say developers of popular productivity software from Prodoscore.

Prodoscore, citing its milestones for 2021, reported a 200% year-over-year revenue growth, and a 100% growth in licenses sold – with more to come.

“We’re confident that within the next couple of years, productivity intelligence will become a necessity in every business,” said Prodoscore CEO Sam Naficy.

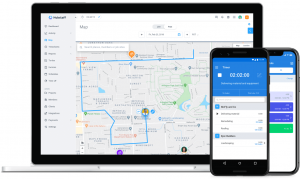

Tracking tools, such as a GPS-enabled app that can be loaded on Android or iOS mobile devices, are used in popular workplace productivity software tools like those from Hubstaff.

In Canada, Hubstaff reported it signed up some 550 companies to a free trial of its employee monitoring software during the pandemic period. Among its tracking tools, the company has a GPS-enabled app that can be loaded on Android or iOS mobile devices.

“Surveillance companies are using the pandemic, and the management difficulties associated with remote work, to pitch their monitoring tools, applications and services to employers,” observed authors of the report called Workplace Surveillance and Remote Work Exploring the Impacts and Implications Amidst Covid-19 in Canada, released in September 2021 by Ryerson University.

Nevertheless, the authors added, “[T]he COVID-19 pandemic has not brought to light anything new regarding the monitoring of workers; instead, it has reinforced and accelerated surveillance trends, exacerbating what many workers in Canada have long experienced through both overt and covert surveillance practices” echoing the long-standing concerns of the Privacy Commissioner.

The Ryerson report continued: “Canada’s employers need better guidance and enforcement to ensure that the treatment of workers and their information is reasonable, appropriate and best engenders privacy, security and trust.”

The Laws Must Change One Day

Unfortunately, there are no enforceable laws in Canada which would specifically prevent business owners from using workplace surveillance techniques and technologies – at present. However, Canadians do have privacy rights under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA).

Among other things, the Act says that anyone gathering personal information or identifying data be open and accountable in their surveillance activities. Such surveillance must be demonstrably necessary for a legitimate business need, with no less invasive means of fulfilling the need.

One of the overarching factors in privacy rights, informed consent, is now a key component of new legislation specifically addressing workplace surveillance, and part of several legislative changes related to the workplace in Ontario.

The provincial government there has passed Bill 88, the Working for Workers Act, which among other things, requires most employers to outline a “right to disconnect” for employees.

The Bill, which has now received Royal Assent, also includes the requirement for employers to tell their employees if and how they are being monitored electronically – for both in-person and remote work.

Organizations will need a written contract in place outlining not only how electronic devices such as company computers, cell phones and GPS systems are being tracked, but why the information is being collected in the first place. Employees should be made aware of what information is being collected, who will have access to it, the reason for collecting it and using it, and what potential consequences might arise from its collection and storage. The new legislation applies to companies with 25 or more employees.

With provincial developments leading the way, calls for the federal government to bring a unified framework to the protection of worker privacy are also being made.

Liberal MP Michael Coteau has called for such worker protection, and he has launched a public consultation process which could lead to a national private member’s bill to protect the digital privacy of Canadians who work from home.

How’s Your Day Goin’?

Technical and legislative initiatives aside, developments in workplace surveillance should always include the question, ‘If an employee isn’t being productive, is there another way to find out why?’

(COVID or not, Zoom or not, pretty much every encounter I have with a co-worker includes a perfectly reasonable question like, ‘How’s your day goin’?’ or ‘How’s your week been?’ It’s workplace surveillance of a much less intrusive nature!)

Regular communications between employee and supervisor, worker and employer, should always take place. Traditional performance evaluations and regular reviews can and should include clear feedback, catch-ups and coaching, expected and agreed upon workloads, and mutually beneficial metrics to assess them. In the case of unionized work environments, all involved should use the collective agreement to define what rights, restrictions and limitations exist regarding workplace monitoring and surveillance.

Yes, surveillance does seem to change employee behaviour, yet there is reason to believe that good interpersonal relations are at least an effective – if not a more so – way to assess productivity. A perceived lack of trust and professional respect is a real demotivator for employees, and widespread use of productivity monitoring software can signal that distrust.

So even if an employer has a legitimate purpose for collecting and using employee information, it must still be reasonable and consensual to do so – and seen to be so by all those affected.

# # #

The authors of a recent report on workplace surveillance note that the COVID pandemic has reinforced and accelerated previously observed surveillance trends. Illustration from Workplace Surveillance and Remote Work: Exploring the Impacts and Implications Amidst Covid-19 in Canada. Masoodi, M.J., Abdelaal, N., Tran, S., Stevens, Y., Andrey, S. and Bardeesy, K. (2021, September). Retrieved from https://www.cybersecurepolicy.ca/workplace-surveillance