More than 15 years ago, a small Toronto-based media company began developing a unique tool we all could use to add fun and creativity and personalization to our online communications. We needed little or no artistic skill, just an urge for self-expression. And a desire to do more than simply type out text-based emoticons.

The original idea was to let people add illustrations, drawings, symbols and objects into an animated composition very easily, in a fun process nowhere near as complex to do as a stop-motion film and frame-by-frame animation. Nor as hard as cave drawing.

The first version of Bitmoji was released in 2007, then called Bitstrips. It allowed users to make personalized comic strips. Years later, Bitstrips launched a spin-off app known as Bitmoji, so users could create customized cartoon caricatures of themselves and stickers with ‘personal moji’ for use in messaging apps. In July 2016, Snap Inc. acquired the company, shut down the Bitstrips comic service but kept Bitmoji in the mix.

Today, there are mojis all over: bitmojis, animojis, memojis and other feature- and sometimes platform-specific variations. They’re all types of personalized, colourized, customized avatars we create to represent our emotions, our desires, our styles, our moods.

There is an official app for making Bitmojis for the major platforms.

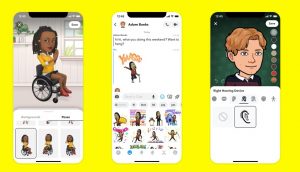

There is an official app for making Bitmojis for the major platforms, iPhone, iPad, and Android (you should have a Snapchat account or link to Snapchat). Bitmojis can be shared right from the app (or a compatible keyboard).

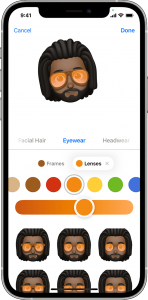

By incorporating a graphical representation of our face (captured via digital camera or webcam) that’s given cartoon-like colouring and styling, mojis are today’s digitized, mediated, instantly recognizable sign of self.

Of course, these little cartoon signatures are shared widely and sent across different social media accounts, chat messages and status updates.

They may be the best (the last?) ways we have to express ourselves in the digital world, to visually interact online (where it is becoming more and more important for us to have a version of ourselves that can function in a technical space, while still representing us as real and authentic human beings). Mojis are a way to stay connected to friends and family − but also to ourselves − in a world that is more and more technologically mediated.

Fifteen years on, Bitmojis stand as kind of elder in the community, thanx to their longer pedigree and almost universal appeal and use. But they have not kept still.

More than 1 billion Bitmoji avatars have been created globally, and 85 per cent of the 13-24 Gen Z population have a Bitmoji avatar, according to parent company Snap. The Bitmoji community has sent over 160 billion Bitmoji stickers.

Bitmojis continue on their more-than-decade-old growth trajectory, and there’s a continually expanding library of image options. In 2018, Snapchat announced its new Bitmoji Deluxe feature, making available hundreds of new skin tones, hairstyles, eye and hair colours, even facial features that convey mood and expression. When it comes to fashion and clothing options, there are said to be over a trillion possible outfits available, creating endless opportunities for different daily digital wardrobes.

The range of possible characteristics exhibited by an avatar expands to allow for even greater personal representation.

And in an admirable bid to bring added representation, diversity and inclusion to the range of possible personal characteristics exhibited by an avatar, Bitmoji introduced wheelchair stickers in 2021, which became very popular in the Bitmoji Chat channels, where users shared wheelchair stickers eight times as much as other users.

Wheelchairs, hearing devices, even colourful walking canes are now part of the sticker selection, and the company says it is open to more ways it can reflect its users as it prioritizes principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility across its platforms.

Applying those principles – represented by their acronym, IDEA – is always a good idea, and among the best ways to build shared community, boost social interaction and maintain good human relations.

In a moji app or otherwise.

Digital avatars celebrate the 15th anniversary of Bitmoji, an easy and creative way to express ourselves visually in the online world.

# # #