Following the lead of several international jurisdictions, Canada is banning the TikTok social media application from government-issued phones. The move follows similar bans in the European Union, the U.S. Senate, as well as individual states and provinces.

Because TikTok’s data collection methods may leave users vulnerable to cyberattacks, the government says, it presents “an unacceptable level of risk to privacy and security”.

The Canadian ban comes after the nation’s top privacy officer, as well as provincial privacy counterparts, announced an investigation into how the app handles the personal identifying information it collects (and whether such collected data is potentially shared with the Chinese ownership and government).

Other apps have not been similarly banned, although the government does warn all users by saying “[s]ocial media and instant messaging services such as Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, WhatsApp, LinkedIn and WeChat … can provide threat actors easy access to your information and devices. You can even be placing your online identity and that of your friends and family at risk.”

The TikTok application will be removed from government-issued mobile devices as of today, February 28, 2023. Users of those devices will also be blocked from downloading the application in the future.

Nevertheless, while noting that TikTok’s data collection methods mean “the risks of using this application are clear”, the government has no evidence at this point that government information has been compromised.

The impact on other users, especially kids, may not be as inconsequential to date: once ranked as the most popular social app among Canadian kids, TikTok’s impact has also been said to be “killing kids’ ability to learn”, among other warnings and portents. Parents have been reporting their own surprising finds while using, or watching their kids use, the app.

Paul Bennett, the director of Halifax-based firm Schoolhouse Institute and adjunct professor of education at Saint Mary’s University, has long cited social media apps’ negative impacts on children’s development, social interaction and educational stamina, but TikTok may be the worst, according to his writing and research.

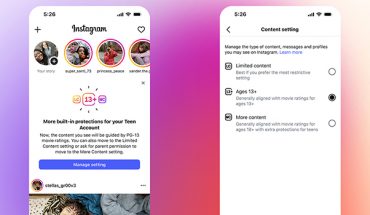

The Canadian privacy commissioners do acknowledge there is a heightened importance to protecting children’s privacy.

“The joint investigation will have a particular focus on TikTok’s privacy practices as they relate to younger users,” their statement describes, “including whether the company obtained valid and meaningful consent from these users for the collection, use and disclosure of their personal information.”

The investigation will examine TikTok’s compliance with various existing Canadian privacy laws, such as the federal Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) as well as provincial statues in Quebec, Alberta and British Columbia.

However, PIPEDA does not differentiate between adults and youth; in fact, for kids over 13, “the child’s level of maturity” is the only limitation on their giving consent.

It’s a key point underscored by Canadian tech developer and entrepreneur Jason Williams, CEO of Vancouver-based Kidoz Inc., which develops software and operates an international mobile advertising network focused on kids and kids’ content.

“Children do not have the power – nor should they – to consent to companies’ collecting, profiling, sharing and monetizing their data,” he says. “That’s a right to be reserved for adults.”

Eighteen or older, in other words, as in many jurisdictions worldwide.

The fact that the digital ecosystem once drew the consent line in the sand at age 13 seems an arbitrary decision now, Williams adds, considering our growing understanding of data rights and values – and the fact that some international jurisdictions have upped the legal age of consent to 18.

Kidoz, he points out, does not require consent for data gathering, because it does not store, save or share user data.

Aiming for a safe, relevant and compliant way to deliver online advertising, Kidoz has built a digital ad monetization system that uses smart contextual information to rank, assess and align content and audience, not data-based targeting.

Such a shift – away from data collection-based targeting towards contextual content analysis – could signal a healthy swing of the privacy pendulum, Williams says.

As the age of consent rises within a carefully constructed legal framework, as context replaces data as a key targeting tool, as consumer awareness about the risks – and rewards – of our online interactions increases, clever technological solutions that have real business value can be successfully brought to bear on important issues like online safety and child protection.

A joint investigation by Canadian Privacy Commissioners will focus on TikTok’s privacy practices as they relate to younger users.

-30-