A Canadian company is staking out the final frontier – space – by sending up nanosatellites to provide Internet access and connectivity for the Internet of Things (IoT).

There are some big forecasts for this small technology: the market for micro- and nanosatellites will pass $4 billion in less than ten years!

Generally described as weighing less than 10 kg or so, nanosatellites (aka microsatellites and CubeSats) can now deliver lots of high-speed Internet access and bandwidth enough for IoT services. There are still huge chunks of the planet and its population that do not have access even to basic Internet service, much less high throughput broadband – some say as much as 80 per cent!! – and while that’s certainly an attractive potential market, there’s also need for satellite-based services in already well-served areas, including North America.

Small satellites can deliver connectivity directly to individual homes, private businesses or public institutions. They can be placed in a specific orbit so as to deliver broadband services to remote regions, and they can serve users in motion – ships at sea, for example. Some companies also provide community hotspot solutions that bring satellite-enabled broadband Internet to people without individual access.

Such factors are among the reasons why reports from industry analysts at companies like Northern Sky Research and Grand View Research show that market growth in the satellite services sector will be a more-than-healthy 13 or 14 per cent annual compound rate as new and ever-smaller communication satellites are designed, developed and launched.

There are several global competitors in the growing satellite services business, and one of the fastest developing companies is based in Toronto.

Just recently, Kepler Communications completed another round of funding that’s now raised more than $20 million (USD) in support of its mission to provide connectivity services from space.

Perhaps even more significant, the company has now received approval from the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to deliver its satellite communication services in the U.S. market.

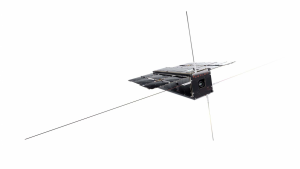

Nanosatellites (aka microsatellites and CubeSats) like the Kepler KIPP bird can deliver lots of high-speed Internet access and bandwidth enough for IoT services.

Kepler is already delivering such services in the planet’s polar regions, where connectivity options are severely limited and many potential customers have been completely without Internet service.

“We’ve spoken with icebreakers, oil tankers, tourism companies, maritime operators and scientific organizations that all operate at the poles,” described Kepler’s CEO, Mina Mitry. “They told us of the frustrations with the complete lack of high-bandwidth coverage in these regions. This is what led us to roll out PolarConnect, the world’s only high bandwidth solution designed for the poles.”

Kepler’s CASE satellite was launched on India’s Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) in mid-November.

Using its first generation satellite, called KIPP, a 60 cm diameter VSAT (Very Small Aperture Terminal) antenna, Kepler can deliver bandwidth up to 40 Mbps to customers that previously accessed other services that peaked around 1 Mbps. Last month, the company put into orbit a sister satellite configuration, called CASE. It was launched from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre on India’s Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) in mid-November 2018.

After KIPP and CASE, Kepler is planning to deploy its third satellite, TARS, in 2019. It will be used to demonstrate Internet of Things (IoT) services. The focus on IoT connectivity is fueled by the most recent round of investment.

Kepler will be using the new capital to grow revenues, and to launch its GEN1 constellation of satellites, which will be put into service by the end of 2020 and includes up to 15 additional nanosatellites. The focus of their GEN1 constellation will be on delivering their high-capacity and affordable store-and-forward services beyond the capabilities offered by KIPP, CASE, and TARS.

Kepler operates major satellite gateways, including one in Canada’s Far North. Kepler Communications image.

Even as this Canadian tech company builds out its satellite infrastructure in space, it is also boosting capability and capacity on the ground. Kepler operates a major gateway in Inuvik (with a 300 Mbps throughput), and it has also recently put ground stations in Norway and New Zealand. As new gateways are added, the company says it can increase service reliability and decrease latency in data delivery.

As mentioned, nanosatellites are part of a huge potential market, and Kepler is certainly not the only company seeking its share: it was one of 11 companies seeking that valuable FCC satellite approval, for example, but there are many more.

One of the largest, if not most visible, is SpaceX’s Starlink, with its rather ambitious goal of encircling the planet with satellites. Only two birds have been launched so far, but plans call for nearly 12,000! That constellation will deliver constant, consistent global Internet coverage, says company founder Elon Musk.

Long-time satellite-based connectivity provider Iridium is providing IoT services, in collaboration with Amazon’s AWS cloud services, and there are well over 20 other companies using nanosatellites to provide low cost IoT services.

Even Facebook is planning to launch an Internet satellite, called Athena, in early 2019.

Audacy, Al Yah Satellite Communications, the Boeing Company, Ball Corporation, Hughes Network Systems / EchoStar Corporation, Israel Aerospace Industries, Lockheed Martin, Myriota, Northrop Grumman, O3b Networks (a subsidiary of SES), Space Systems/Loral, LLC (SSL) and Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems are among the many companies using nanosat technology to target specific regions of the planet, from Africa to the Middle East to South America and southwest Asia, with Internet access and IoT connectivity services.

-30-