Billions of pounds.

Tons of kilograms.

Lots and lots of e-waste.

Around the world and here in Canada, we’re generating way more electronic scrap than we are collecting and recycling. Five times as much. And what we throw away is, ironically, both very valuable and very dangerous.

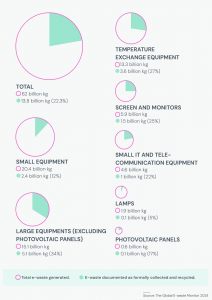

It’s not only the consumer tech gadgets we first embrace so enthusiastically (our laptops, mobile phones, smart devices and more) and then discard so carelessly (there’s only a 22 per cent documented collection and recycling rate); it’s a burgeoning array of industrial and institutional products, like temperature exchange equipment or photovoltaic power panels. A lot of e-waste now comes from ‘the cloud’ and the huge data centres behind it: IT equipment like servers, switchers, monitors, transformers, power distribution units, fibre optic tubes and cabling galore.

More than 68 million tons of e-waste were produced in 2022, according to data from the United Nation’s fourth Global E-waste Monitor report.

All told, more than 68 million tons of e-waste were produced in 2022, according to data from the United Nation’s fourth Global E-waste Monitor report. That’s way up (82 percent from 2010), perhaps not surprisingly.

And we’re on track to reach approximately 90 million tons by 2030.

As the researchers and authors of the report, conducted by The United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), point out: that’s a 33 percent increase from the 2022 figure, and definitely not the way to go.

“Simply put, business as usual can’t continue,” Kees Baldé, a lead author at UNITAR, said bluntly. “This new report represents an immediate call for greater investment in infrastructure development, more promotion of repair and reuse, capacity building and measures to stop illegal e-waste shipments.”

Whether it is called recycling (or one of the other Rs we’ll talk about) or information technology asset disposition (ITAD), the e-waste we throw away is very valuable: The UN/ITU report estimates the metals embedded in landfilled e-waste from 2022 to be worth more than $90 billion, including $19 billion in copper, $15 billion in gold and $16 billion in iron (all figures USD).

Of course, e-waste is very destructive, too: improper e-waste disposal poses a serious threat to public health and global ecosystems. E-waste contains toxic materials or can produce toxic chemicals if not treated or disposed of properly, lead being one of the more common substances that can be released into the environment when e-waste is recycled improperly, stored carelessly, or just plain dumped.

But as the UN/ITU report points out, less than one quarter (22.3 per cent) of our e-waste was documented as having been properly collected and recycled.

The United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) released a damning report on global e-waste. This image shows waste awaiting recycling at a centre in Germany.

Alarmingly, the report predicts a continuing drop in the documented collection and recycling rate to 20 percent by 2030, partly due to an inconsistent use of recycling efforts and lack of infrastructure relative to the growth of e-scrap. The report’s authors say the decline in recycling and the gap in global efforts to reduce e-waste are also due to the high rate of so-called technological progress, coupled with higher consumption, limited repair options, shorter product life cycles, design and product shortcomings, and inadequate e-waste management infrastructure.

“The latest research shows that the global challenge posed by e-waste is only going to grow,” noted Cosmas Zavazava, director of the ITU Telecommunication Development Bureau. “With less than half of the world implementing and enforcing approaches to manage the problem, this raises the alarm for sound regulations to boost collection and recycling.”

Canada is, unfortunately, part of the world: researchers at the University of Waterloo released a report showing that we generated close to a million tonnes of e-waste in 2020 – and that less than 20 per cent of it was collected and recycled! Published in the Journal of Hazardous Materials, their study shows the amount of electronic waste steadily increasing in Canada, having tripled in the last 20 years.

Be it a result of inadequate laws, lax enforcement, short product lifecycles or other market factors, that e-waste increase comes even as most provinces in Canada have programs developed by industry or policy to ensure e-waste is disposed of in economically responsible, environmentally friendly ways. Across the country, EPR or Extended Producer Responsibility programs are in place to get industry to take environmental stewardship and post-consumer responsibility for their products.

The City of Toronto shows some of the electronic products it will accept as waste.

In Ontario, electrical and electronic equipment regulations (including recycling e-waste) fall under the Resource Recovery and Circular Economy Act (last updated in 2020) and the government’s regulator, the Resource Productivity and Recovery Authority, where electronic product recycling information is available.

Likewise, organizations such as EPRA/Recycle My Electronics work directly with businesses and municipalities across the country to address the growing e-waste problem within existing regulatory requirements.

Taking a slightly broader tack, the Electronic Recycling Association (ERA) seeks to reduce electronic waste and promote sustainability by repurposing usable yet no longer needed devices and making the technology accessible to those who need it.

The non-profit organization sees how recovery, refurbishment, and reuse of electronics and computer equipment can be a way to address the growing problem of e-waste while trying to bridge the increasing ‘digital divide’. Working with individuals and charitable groups across the country, ERA has been operating since 2004.

Meanwhile, the handling, sorting and remarketing of obsolete and discarded electronic devices for organizations of all sizes is creating new opportunities in the private sector. As just one example, Toronto-based information technology asset disposition (ITAD) company Quantum Lifecycle has just opened its sixth operation in Canada, a 7,800-square-foot facility in Alberta where e-waste from the cloud will be processed.

That e-waste can be refurbished, recycled, resold.

So along with reuse, rescue, and repair, we do have plenty of ideas about how to deal with the piles of electronic waste and e-scrap we create, but more ideas – more R words – could be brought to bear.

Like reduce, as in reducing the amount of e-stuff we buy in the first place. And reconsider, as in reconsidering our personal wants and desires in light of global issues and realities.

-30-