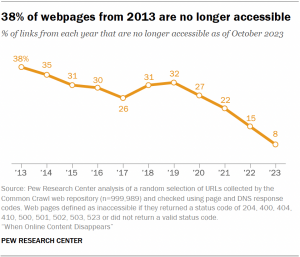

As much as 40 per cent of the content posted to the Internet since 2013 has disappeared.

In some cases, that may cause a collective shrug of the shoulders. But in other situations – researchers, journalists, historians, archivists, and advocates for a free and accessible Internet – a recent study from the Pew Research Center is cause for concern.

The American think tank says “digital decay”, “link rot”, and other causes of content disappearance show us “just how fleeting online content actually is”.

A recent study from the Pew Research Center says “digital decay”, “link rot”, and other causes of content disappearance show us “just how fleeting online content actually is”.

In most cases, researchers found that individual pages were missing, removed, or deleted from otherwise fully functional sites with other content still available. The older the content, the more likely it was to go missing: less than ten per cent of site content posted in 2023 is gone – barely a third of the sites that existed in 2013 are still around.

The disappearance is happening pretty much everywhere, researchers say: private business and corporate sites; public sector government websites; news archives; even Wikipedia, that great repository of content, where more than half of links now lead nowhere. And on the ex-Twitter social media site, nearly one in five tweets disappear within months.

(Again, that may cause a shrug of the shoulders, maybe even shouts of joy, but taken as a whole, disappearing content can limit the depth, detail, and accuracy of any attempt to paint a representative picture of our world, our culture, of us.)

There are many reasons that online content or individual web pages or entire sites may disappear: the outright shutdown of a website by its owner for financial or other operational reasons; a lack of interest/audience; possibly even because the site’s goals were reached. For sites that stay online and regularly refresh their content, old pages might be deleted or overwritten during updates or redesigns, particularly if the content is no longer deemed relevant.

Not hard to find: rotten links leading to 404 error messages that is, denoting disappeared content on the Web. A useful link from an older WhatsYourTech.ca story now leads nowhere.

Sometimes, a site owner has only rented a domain name, rather than purchasing it outright; without renewal, that site will go offline.

Of course, tech issues can be responsible for lost or missing content. Accidents, errors, and server or data corruption issues, coupled with a lack of proper back-ups, can be devastating. So, too, purposeful destruction or hijacking of content such as caused by cyberattacks.

Nowadays, privacy concerns, take-down orders, and copyright disputes are just as likely to cause content to disappear as any of the other causes. Whatever the cause, it often means all the content and associated links are gone.

In a disheartening and destructive coincidence, one of the Internet’s best places to preserve content has been the victim of two reasons – one legal, one certainly not – for content disappearance.

Why hack the Archive? A massive disruption caused by a denial-of-service attack (DDoS) on Archive.org took much of the site’s functionality and content offline.

A massive disruption caused by a malicious denial-of-service cyberattack (DDoS) on Archive.org took place just a couple of months ago, taking much of the site’s functionality and content offline. Hackers stole data, passwords and other content. The site’s much-loved Wayback Machine, which let people access literally billions of older, archived web pages, was affected, but Archive.org publishers have been working to fulfill their stated commitment to bring it all back online.

But, falling victim to that second cause of disappearing content, the Internet Archive will not be able to repost some 500,000 books, having lost a copyright battle with major U.S. publishing companies.

Along with the Wayback Machine, the Archive had operated a Controlled Digital Lending (CDL) system, letting people borrow ebooks, digital copies of hardcopy books the organization had purchased. Publishers wanted greater royalty returns, but the Archive felt the new fees were too expensive. An appeals court sided with the publishers.

Commenting on these and other recent developments impacting content on the Internet, the director of the Wayback Machine project, Mark Graham, noted that “The web is aging, and with it, countless URLs now lead to digital ghosts. Businesses fold, governments shift, disasters strike, and content management systems evolve—all erasing swaths of online history. Sometimes, creators themselves hit delete, or bow to political pressure.”

One partial response to the ‘content ghosting’: accessing archived versions of certain web pages directly through Google Search, with a sample link to the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. Next to the usual Google search result are displayed three small dots: clicking on them will bring up an “About This Result” box, where another link to the Wayback Machine’s stored version is found under “More About This Page”.

A new report explores instances of disappearing content and cultural loss.

Other ebook content is still available, at least for now: the Distributed Proofreaders site hosts a web-based method to convert Public Domain books into ebooks and there’s Project Gutenberg, one of the very first providers of free electronic books.

Understanding with greater clarity and recent research just how vulnerable digital materials are, how by design or attack or other reasons, content can disappear suddenly and permanently, the folks at the Internet Archive have put together a report of their own. Called Vanishing Culture: A Report on Our Fragile Cultural Record, it aims to raise awareness about these issues.

The report details instances of cultural loss, highlights the underlying causes, and emphasizes that our collective memory is compromised, and the public’s ability to access its own story is at risk, as more and more content disappears.

# # #

Disappearing content is a real concern for some; for others, it’s a marketing technique.

AKA ‘ephemeral content’, it’s made up of social media posts that purposely vanish after a set time. Posts to platforms like Instagram Stories, Snapchat, or Facebook Stories typically last for just 24 hours before they’re gone. Images and videos on WhatsApp can be viewed only once before they disappear. Photo: WhatsApp

-30-