Much more information about the use of sophisticated wireless technologies in Canada is needed, and an independent investigation by Canada’s Office of the Privacy Commissioner into the use of mobile phone surveillance equipment by the country’s police forces is necessary.

That’s the word from public advocacy and citizen lobby groups in Canada about the use of so-called StingRays, and what is being called “a massive breach of the public trust.”

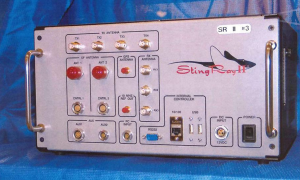

StingRays (a commercial brand descriptor for devices more generically known as cell site simulators or IMSI catchers) are sophisticated gadgets used for intercepting wireless phone traffic and tracking the movement of smartphones and other mobile devices.

StingRays (a commercial brand descriptor for devices more generically known as cell site simulators or IMSI catchers) are sophisticated gadgets used for intercepting wireless phone traffic and tracking the movement of smartphones and other mobile devices.

Sophisticated, but small – they can be easily mounted or carried while in use.

A StingRay device tricks nearby phones into thinking it is a typical cell tower, and by ‘catching’ a phone’s internal International Mobile Subscriber Identity information, the StingRay can then connect to the phone, get its location and other important communications data.

Incoming and outgoing calls as well as text messages can be monitored and recorded, encryption keys can be extracted, and all this can happen to one or several phones simultaneously, without an owner’s knowledge or permission (and without involving the cell phone provider).

“Citizens have a right to know whether or not our local police forces are engaging in mass surveillance, and disclosure of the existence and use of this device is vital in ensuring that individual Charter rights are protected,” Douglas King, a lawyer with Vancouver-based Pivot Legal Society, said about StingRays and similar gadgets.“The use of this device on people or groups of people without judicial authority represents a massive breach of the public trust.”

Pivot Legal filed a Freedom of Information (FOI) request in order to learn about possible use of StingRays by local police forces, and having not received a satisfactory reply, the group has filed an appeal with the province’s information and privacy commissioner.

Pivot notes that Canada’s two largest police forces, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the Ontario Provincial Police, have refused to deny using the devices. The Vancouver Police Department also recently declined to answer similar inquiries.

Police services cite the need to protect possible ongoing investigations, while citizen groups are concerned about privacy protection and personal vulnerability.

The battle for access to operational and procedural information about the use of wireless technologies by police services has raged for many years, and the same three organizations – the OPP, RCMP and VPD – have previously declined to confirm or deny their use of StingRays.

(The FBI apparently uses a secret device to locate criminal suspects, but according to some reports, it preferred to let suspects go free than reveal in court any details about such high-tech tracking.)

It’s been a continuing theme here and in the U.S. – local and national police forces are generally tight-lipped about the use of StingRays, but recent research into public records (such as commercial purchase orders) indicates that at least 38 police departments in as many as 20 states have purchased one, but that research did not include Canada.

(Dyplex Communications is one of several companies providing advanced covert tracking, surveillance and location technologies to government agencies in this country, and it is a distributor of equipment made by cell site simulator companies such as Datong plc.)

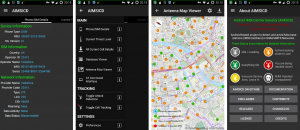

Efforts to secure information about the use of surveillance technologies by public agencies such as our municipal police forces are being encouraged, but while privacy advocates wait for a reply to their calls they may want to load a special app onto their smartphones anyway.

AIMSICD is a mobile app that can detect the detectors, for example, and it can alert a user to any IMSI-catchers in use nearby.

AIMSICD is a mobile app that can detect the detectors, for example, and it can alert a user to any IMSI catchers in use nearby. As an open source solution, the app is constantly being re-evaluated and upgraded by its development community in the hopes in can keep up with developments that may occur in any user communities out there.

-30-

Thank you for your comments, Gina.

Here is a link to a great online resource listing a number of online privacy and security tools: http://fried.com/privacy

Very scary – would love to see a list of iOS apps that enhance mobile security, since the link provided lists mostly Android apps. Great article.