The use of statistics and big data in pro sports is bringing us a whole new ballgame: one with great rewards and great risks for players, teams and fans.

Big data is used at all levels of competitive sport to gain greater insights into player metrics and team performance, and to enhance training and professional development. Big data analysis is surely changing the way the game is played – baseball purists bemoan the accumulated data points that lead to the infield shift, for example – but big data analytics are also changing the way sports are managed and monetized.

The sports analytics industry, according to Research and Markets analysts, is expected to reach $3.97 billion (USD) over the next five years — other estimates say the reach is much greater.

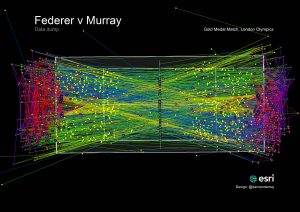

More than 1,700 data points on location were collected and analyzed during the 2012 Olympic Gold Medal Tennis Match. Sports officials and big data analysts can use geographic information systems (GIS), among others, to identify particular patterns within a sports competition that may not be exposed through traditional analysis techniques. esri/ArcGIS image.

The numbers show how widely sports teams, coaches, broadcasters and rights holders are making use of big data to improve performance and connect with fans. It give us a sense of how many technology companies and application developers could play in the market and monetize the opportunities.

Canadian sports analytics company SportLogiq is just one example of companies involved in the sports data analytics sector: from its headquarters in Montreal and new offices in the Kitchener/Waterloo tech corridor, SportLogiq uses proprietary machine learning and artificial intelligence to track player movement and analyze in-game activity, transforming the data it gathers into “actionable insights” used by both the team and the media covering it.

The company was co-founded by Canadian Olympic athlete Craig Buntin and Mehrsan Javan, a PhD in computer vision at McGill; it is backed by businessman, investor and pro basketball team owner Mark Cuban (as well as other team owners and media executives).

The National Basketball Association and Intel Capital recently announced their own sports technology innovation collaboration, designed to identify and grow other tech companies working in the pro sports, technology, data and consumer engagement field.

Sports teams, coaches, broadcasters and rights holders are making use of big data to improve performance and connect with fans – much less to monetize new data-related opportunities. Genius Sports image.

And in a huge three-pointer for collegiate sports, the National Collegiate Athletic Association has signed a ten-year deal with U.K.-based sports data and technology company Genius Sports to collect and distribute intercollegiate sports data. More than 1,100 member institutions and major sports divisions will be served, and the data from incredibly popular NCAA events like March Madness will packaged, licensed and sold to media companies and other interested parties.

Genius Sports will provide development, promotional and technical support for use of its sports data software that can deliver player and game stats to multiple platforms in real-time (as it does for other pro sports leagues in Asia, the U.K. and Europe).

Sports Data Winners and Losers

Of course, even as businesses both large and small try their hand at winning the sports data game, there are and will be losers.

Valuable data can end up in the wrong hands, as sports competitors and commercial pirates try to use the individual or league data to their own advantage. Teams can be undercut in their attempts to recruit or draft up-and-coming players through the misuse of their scouting data. Players can find themselves subject to automated decision-making, driven by computer algorithms that impact their personal and professional lives.

The North American Major Lacrosse League, for example, disclosed last season that a data breach affected every player and every former player on whom the league had information. Personal details and professional accomplishments were exposed and made available to an unintended audience, the league acknowledged.

In its attempt to prevent the same thing from happening on the ice, the National Hockey League Players’ Association (NHLPA) has inked a deal with another U.K. firm, this one a data protection service provider known as Darktrace.

The Darktrace Threat Visualizer dashboard gives sports organizations, among others, the tools they need to avoid data hacks and security threats.

David Masson, Darktrace County Manager for Canada, explained in an announcement that the company is “arming organizations with the AI (artificial intelligence) they need to stay ahead of all known and unknown threats.

“The National Hockey League Players’ Association joins a growing number of organizations (5,000 deployments were cited) that lead the charge in adopting AI cyber technologies to safeguard their critical information assets and avoid reputational damage,” he said.

Not only are there hacks and attacks on sports data, there are specific groups dedicated to doing just that. On their website, a hacktivist collective known as Fancy Bears describes itself as an “international hack team” that “stand[s] for fair play and clean sport.” (The group has also been described as a Russian cyber espionage group, associated with the Russian military intelligence agency GRU.)

A hacktivist collective known as Fancy Bears describes itself as an “international hack team” that “stand[s] for fair play and clean sport.”

The group also hacked the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) and International Olympic Committee (IOC), and has been accused of leaking data about the use of banned medicines in football in the U.K.

The hacking team plays no favourite: “Canada is no different than Russia in covering up doping” the group says on its website, citing other sports data and related information.

Stealing Signs in the Age of High-Tech

So access (legal or otherwise) to sports data has left us with a whole new ballgame, that’s for sure.

While stealing signs has long been a part of baseball (that’s stealing, as in using your eyes to watch the opposition give hand signals for a certain play or pitch, and then mentally interpreting those signals and verbally sharing the conclusion with your teammates), today, stealing signs is a digital process, involving hacked databases, wearable gadgets and popular iDevices.

The case in point is a story about hacking sports data and the Major League Baseball teams in St. Louis and Houston. Turns out one team’s employee “improperly viewed” information in the other team’s database. In other words, he hacked in.

Subsequent investigation and prosecution resulted in court-ordered cash penalties and prison time for individuals involved!

Then, last year, in yet another fight between age-old baseball adversaries, the New York Yankees accused members of the Boston Red Sox of using an Apple Watch to steal pitch signs and get the results to teammates in-game.

MLB has previously fined teams using such high-tech skulduggery, but the ability to gather, analyze and extract value from data in the volumes that are available today means that sports teams must now consider data security, not just sporting performance, as a part of their overall strategy for success.

Players come and go. Jerseys and logos change all the time. Data can be seen as a sports team’s most valuable asset.

From the embedded GPS and data transmission platforms mounted under the seat (pictured) of a competitive cyclist’s bike to the tracking technology stitched into NHL hockey jerseys to the ring of cameras and Doppler radar sensors circling a baseball diamond, digital technology and big data analytics are changing the rules of the game. Dimension Data image.

-30-