A new report from Canadian and American technology researchers shows how third parties are the first threat to online privacy and data security.

It really doesn’t matter what website you are visiting: its owners, operators and publishers regularly work with what are called third parties, other companies that provide ancillary services for the website.

Third-party website services (or content) can provide value and utility, as they say, with improved website performance, better website functionality and more relevant advertising for the user. For the website owner or publisher, providing user data in return for third-party services is a kind of revenue stream.

But, either offered up by the user in return for the value of visiting the website or gathered by use of website trackers, cookies, beacons and the like, the collected data is also shared with various third parties in the monetization chain, often without the user’s direct knowledge or informed consent, and often several times over.

The first threat to our online personal data may be the activities of third-parties. Creative Commons image by Joseph Seamans.

Companies can assemble a comprehensive history of what websites you visit, for how long and in what order, what purchases you made or content you viewed while there, and so on. Browsing history is one thing, but other tracking cookies can record the type of device you use, its – and therefore your – location, and the list goes on.

The data is valuable not just to third parties which offer online services such as targeted advertising or product purchase recommendations; the collected and collated data can also be used in the development of machine learning algorithms and other, well, more nefarious purposes.

As such, concerns about online privacy and data security are growing when it comes to the practices associated with third-party monetization of personal data online.

Those concerns are growing almost as fast as the industry itself: in 2017, U.S. companies alone spent just over $10 billion on third-party data, as reported by the Interactive Advertising Bureau Data Center of Excellence and the Data & Marketing Association. Projections anticipate a 17.5 per cent increase in spending on third-party data and related technological infrastructure this year.

Haskayne School of Business professors have co-authored a study that examines how website publishers share user data with third parties, and the growing privacy concerns associated with the practice. Photo by Riley Brandt, University of Calgary.

That’s one reason why the new technology report, co-authored by two professors at the University of Calgary’s Haskayne School of Business, Hooman Hidaji and Ray Patterson, along with researchers from U.S. universities, is so concerning.

Called How Much to Share with Third Parties? User Privacy Concerns and Website Dilemmas, the report documents how a user’s simple website visit can trigger many interactions with third parties, as well as the extent and immediacy with which that data is shared.

“Within the first two or three seconds of landing on a website, your data is often shared with dozens of third-party firms,” described Patterson, a UCal business technology management professor.

The report’s authors also noted that the problem of selling and reselling consumer data to third-party providers is potentially much worse than they were able to determine. The report did not track the data interactions among third parties, so the extent of commercial use of personal data is likely much greater than reported.

With or without such shortcomings, Hidaji says the report reveals large-scale collection and sale of user private data has grave implications for the safety, security and protection of that data.

The unprecedented amount of data collected through online tracking and targeting tools provided by third parties is a valuable target to hackers, for example. And the website functionality created by those third parties is itself often the broken link in a chain meant to protect the data in the first place.

In the case of the American retailer Target, the personal data connected with some 40 million credit card accounts was stolen through a third-party relationship.

Likewise, credit card data was skimmed from Ticketmaster when hackers got through an online payment form created by a third-party supplier. Such developments are not seen as a one-off, but rather as a new kind of strategy for stealing personal data: lots of popular e-commerce websites use similar third-party tools, widgets or components.

So criminal activity like personal data theft is a clear and present danger: but so too, the report authors say, a subtle – and apparently legal – kind of systemic discrimination is engendered by third-party data collection and analysis.

Hidaji and Paterson point out that the same data can be used by one company to offer certain products at certain prices to certain customers in a certain location, but not others: that kind of manipulated pricing or controlled product availability can tip the market in favour of very specific demographics and away from others.

All that collected data can be traded by data brokers, companies like Experian, Oracle, Acxiom and Epsilon, whose primary business interests are credit scoring, database management and marketing technology. Part of Oracle’s data trading pitch says clients can “[d]eepen your connections with existing customers by layering on purchase-based, in-market, or behavioural third-party data…” (emphasis added).

The report looks at how the tracking tools and website functionality provided by third parties are not offered in a vacuum, and in fact can overlap in comprehensive ways: Alphabet, Google’s parent company, owns several of the tracking domains that were studied, including Google Analytics, DoubleClick or AdMob. Google has more than 40 third-party domains used all over the planet, Microsoft has nearly 20, eBay has a bunch and the list goes on.

Another study looked at the third-party data collecting that goes on with popular smartphone applications.

Perhaps not surprisingly, researchers found data being shipped across national borders, often ending up on servers in the U.S., U.K., France, Singapore, China and South Korea – some of the countries that have deployed mass surveillance technologies to make extra use of the kind of data collected.

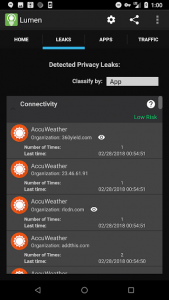

The Lumen Privacy Monitor tracks which trackers are tracking you. Its developers say more than 70 per cent of smartphone apps are reporting personal data to third-party tracking companies.

And not surprising either are results from a similar study looking at the third-party data collecting that goes on with popular smartphone applications.

Researchers Narseo Vallina-Rodriguez and Srikanth Sundaresan built an app that monitors communications between the other apps on a smartphone and the known third-parties that track user activity.

More than 70 per cent of smartphone apps are reporting personal data to third-party tracking companies like Google Analytics, the Facebook Graph API or Crashlytics. Some fifteen per cent of the apps used five or more trackers; a quarter of the apps used unique identifiers that can track users across different devices.

The UCalgary report also noted that rules, regulations and laws meant to be the first line of defence against online hacking and the misuse of data are not all that effective, sadly.

The authors said that the end user, and his or her own active participation in the protection of their own personal data, may be the best defence. Website publishers and even third-party providers can be sensitive to the perceptions and attitudes of their customers.

If end users are more vocal about demanding protection for and control over their data, third-party suppliers and providers may have to eventually respond in the first person.

-30-