Sore feet, strained muscles, high blood sugar levels and even pregnancies are being monitored by a new generation of health care products.

Embedded with biometric sensors, wireless transmitters, input/output connectivity, custom software and other proprietary technologies, they are comfy computers that we can wear day and night.

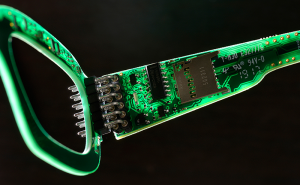

Do glasses make you look smarter? Or will they actually make you smarter? French tech company Ellcie Healthy has introduced glasses whose frames are packed with data-collecting sensors and transmission tools so that physical, physiological or even environmental data can be monitored and analyzed as a way of boosting health and safety, from keeping drowsy drivers alert to helping mobility-challenged seniors stay upright. The company offers (for now, only in France) smart glasses for specific consumer and medical purposes. Ellcie Healthy image.

Smart clothing is being used to capture near-constant streams of biometric data about the wearer in real-time, measuring and analyzing core physiological functions like body temperature, respiration and heart rates as well as more subjective human signals such as stress levels and emotional comfort.

Of course, more than being merely measured, these biometric signals can be utilized as part of medical diagnostic activities and treatments. The data gathered from users are being used for predictive, preventative and on-going medical management activities by health care consultants and medical practitioners.

Not surprisingly, some observers are concerned the data may be used for other purposes, often unknown to the user and unregulated by privacy legislation.

Nevertheless, the potential for enhancing or increasing human health and wellness is enormous from the medical and marketplace point of view.

Wearables, health trackers and patient monitoring gadgets will bring in more than $20 billion in device sales in the next few years, and the service-related side of the industry could generate another $40 billion, according to industry analysts.

Sector-specific analysis from Juniper Research says improvements in health-related wearables and remote patient monitoring technologies will help serve more than five million people in the U.S. by 2023.

They may well be using medical wearables made in Canada.

A Calgary-based company is developing a high-tech shoe developed so people with diabetes can take control of their disease and manage its negative impacts – like amputations.

The Orpix SI system includes a sensor-embedded shoe liner, a connected smartphone app and analytical tools used by both patient/users and medical practitioners. Orpix image.

Diabetics can lose sensation in their lower extremities due to poor circulation, and nerve damage can result. So a patient may be unaware of any soreness or irritation that can lead to further complications, like foot ulcers and, sadly, amputation.

Orpyx Medical Technologies offers a range of “accessible and beneficial sensor-based technologies and sensory substitution systems” – kind of high-tech speak for shoes that walk and talk. The Orpix SI system includes a sensor-embedded shoe liner, a connected smartphone app and analytical tools used by both patient/users and medical practitioners in diagnostic and treatment programs.

Connected shoes and active soles are part of smart footwear from other developers worldwide, including the Japanese sportswear company Asics and an Italian company called Wahu, among those with products that can analyze leg and foot activity, pressure, impact and temperature to enhance training,athletic performance or basic health.

Montreal-based Hexoskin embeds not shoes, but shirts, with technology to enhance health and physical awareness.

Its high-tech smart garments include a sensor to monitor steady heart rate and post-activity recovery times, breathing rates and respiration activity levels and other body signals as a way to inform users (and health care practitioners and researchers) about how activity, stress and fatigue interact with cardiac heath and respiratory functions.

Hexoskin wearables feature Bluetooth capability, standalone data recording, compatibility with Apple and Android systems, as well as extended battery life. Hexoskin image.

Core Hexoskin tech specs include Bluetooth capability, standalone data recording, compatibility with Apple and Android systems, as well as extended battery life.

While many wearables are collecting digital information, not that many are responding to it.

But Toronto-based start-up Myant has embedded sensors and actuators into its textiles, creating wearables that can both sense and react to signals from the human body

Its line of smart wearables, called Skiin, incorporates sensors embedded into the fabric they are made of, the company describes, and that interface means it can gather data about heart rate, physical activity, sleep apnea and other conditions – in pregnancy, of both mother and fetus – not only from worn clothing, but also chair upholstery, bedding or other textiles that contact the body. Collected data can be distributed to cloud-based, AI-enabled health care analysis programs using the system.

Myant, along with its partner the ZOLL Medical Corporation, reports it is working on a wearable defibrillator known as a LifeVest. By monitoring the wearer’s heartbeat and cardio status, it could detect signals of a upcoming cardiac incident for patients at risk of sudden cardiac death and even take appropriate responsive action.

Myant’s textile-based computing products have been recently named as a CES 2020 Innovation Awards Honoree. Myant image.

Myant’s textile computing products and apps, including the Skiin Connected Health & Wellness line, have been recently named as a CES 2020 Innovation Awards Honoree.

Hard to argue against saving life and limb with wearable tech, but fairly easy to at least prescribe caution, as Juniper Research report author Michael Larner suggests:

“Data privacy and consent will continue to be a significant barrier” to continued development and adoption of wearable tech. While we can use such platforms to improve health care systems and hopefully outcomes, the successful – and legal – use of its data collecting devices and AI-enabled analytics will depend on patient data protection, awareness and confidence. “It is vital that patients are made aware of how their personal data will be used.”

And, it’s smart to add, by whom.

-30-

tnx for information