Get ready for the next emergency – test, that is.

In less than two weeks, many Canadians will receive an emergency alert as part of a routine test of the Alert Ready system. That’s the national system used to deliver government alerts and special notifications across the nation’s communications ecosystem, including TV, radio, and compatible connected mobile devices.

On November 25, the system will be put through one of its regular tests and, in Ontario, that’s scheduled for around 12:55 pm; in B.C., it’s an hour later (local times cited).

On November 25, the system will be put through one of its regular tests and, in Ontario, that’s scheduled for around 12:55 pm; in B.C., it’s an hour later (local times cited).

Actual Alert Ready messages are often weather-related, warning of extreme climate conditions like flooding, fires, tornadoes and the like. The delivered messages can also convey important information about missing persons, especially kids, as Amber Alerts. The system has also been used to push out notifications about nuclear emergencies (and, in at least one rather awkward case, about nuclear events that are NOT emergencies!).

Yet the current national emergency we all face, one that is, in fact, global in nature, has not been mentioned in any nationally distributed alert message. While most Canadians feel the government is doing a good job handling the coronavirus crisis, another recent survey revealed that a majority of respondents thought that the national alert system should be used to deliver alerts and information about COVID-19.

Particularly as certain regions and jurisdictions adopt new criteria for assessing and determining restrictions on social activity — or to use that unfortunate term, lockdown — the need for fast, reliable, clear and consistent messaging is greater now than ever before.

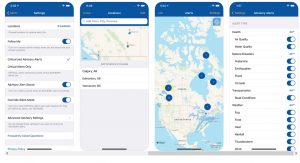

That survey about th possible uses of the alert system was conducted by a Calgary-based technology company called Public Emergency Alerting Services Inc., or PEAsi. It has developed a mobile notification app called Alertable, a commercially available emergency alerting platform that is fully integrated with Alert Ready.

Released some two years ago, the free Alertable mobile app is used to deliver messages to iOS, Android, and Web pl atforms, as well as on the Alertable social media pages on Facebook and Twitter. Integration with smart speakers like Alexa Echo, Apple HomePod, and Google Home, as well as with online communications platforms like Slack, Facebook Messenger, and WhatsApp, is in the works.

atforms, as well as on the Alertable social media pages on Facebook and Twitter. Integration with smart speakers like Alexa Echo, Apple HomePod, and Google Home, as well as with online communications platforms like Slack, Facebook Messenger, and WhatsApp, is in the works.

Alerts can be sent in English and French and the developer says the Alertable app meets Federal and Provincial accessibility guidelines. The company provides not only the technical capabilities to deliver such messages, it works with message originators to ensure the content itself is clear, concise, effective, and easily understood by the target audience.

In conversation with Jacob Westfall, the company CTO, it was explained that the prime customers for PEAsi’s emergency notification system are municipalities and the most common reason is weather-related, yet the need to communicate with the public is growing.

“It’s definitely a growth area, the need for better communications – that’s our Number One finding. And not just from the government to the public, but also internally among regional agencies and different public service providers and agencies. COVID shows it’s a universal need.”

Public alerting plays a very important role in any natural disaster, including a pandemic. Technology cannot yet stop the effects of the pandemic, but it certainly can ease the lives of those suffering from those effects by educating, warning, alerting, and empowering people to make appropriate decisions, based on reliable and reproducible data.

And on a global scale.

Westfall is deeply involved with the international development of standards and platforms for emergency notification delivery, as well..

There is in fact a CAP, Common Alerting Protocol, which underpins apps like Alert Ready, Alertable, and other regional or national variations on that theme. As a lead author on the spec, Westfall noted how beneficial an open, non-proprietary digital message format for all types of alerts and notifications can be.

There is in fact a CAP, Common Alerting Protocol, which underpins apps like Alert Ready, Alertable, and other regional or national variations on that theme. As a lead author on the spec, Westfall noted how beneficial an open, non-proprietary digital message format for all types of alerts and notifications can be.

The primary use of the CAP Alert Message is to provide a single point of contact for all kinds of alerting and public warning systems.

Interestingly, a secondary application of CAP is to be able to aggregate and analyze warning-related data as an aid to situational awareness and pattern detection. In other words, how was the message received and what did people do when they received it.

The Canadian CAP working group brings that open content into a specific Canadian context, taking into account language differences, regional jurisdictional priorities, and other specific user profiles.

Westfall is also among the technologists, engineers, and system architects who are involved in the OASIS Emergency Management Technical Committee, a multinational open standards consortium.

That group has just demonstrated how information can be transmitted between and among a suite of compatible standards, including CAP, new digital messaging systems, and an expanded Emergency Alert System (EAS) that not only can connect the public, using a variety of broadcast media, including radio, television, mobile phones, and personal computers, but also connect first responders, public health officials, and other agencies involved in coordinating an emergency response.

OASIS didn’t say so, but a pandemic clearly requires a coordinated reaction and a cooperative approach, both from public officials and from the public at large.

Triggering that reaction is much like triggering any reaction, be it to a potential flood or to a new product marketing campaign.

Push notifications are known to be effective tools in driving audience awareness and product usage. Push notifications can increase user engagement and improve retention. Digital marketing teams know this; now it’s time for public health officials to use similar tactics and techniques.

Some emergency notifications and pubic health notifications could fall be treated much like a product or brand awareness campaign, and with the new technical capabilities these protocols can bring, those messages can be packaged and presented in new ways. Messages can have digital images and audio. They can come with digital signatures to verify and authenticate the content. Other emerging capabilities include enhanced message update and cancellation features; templated support for framing comprehensive and effective warning messages; multilingual and multi-audience messaging; and time-phased delivery and delayed effective times and expirations.

That enhanced toolset not only can be used to make emergency notifications and alerts more effective in general, they can help address other issues also identified in PEAsi’s survey about emergency notifications and communicating in the age of COVID: Not only did a majority of respondents say that the national alert system should be used to deliver COVID-19 alerts, they felt those alerts should have direct links to government websites and trusted sources of information like public health agencies.

Those trusted sources should deliver daily messages to counter the volume of mis- or disinformation that’s also out there, survey respondents said. Insights and education about how to verify pandemic-related information, in particular, should also be communicated.

# # #

After the upcoming national alert test on November 25, PEAsi will be conducting another survey of sorts, one with a strong crowdsourcing and community feedback angle: people across the country will be asked to send the company pictures, videos, or screenshots that show what the emergency message looked like and sounded like on their phone, computer screen, TV or another device (however they received the alert on the test day).

-30-