Every click you make has a real impact.

But in terms of personal privacy or actual utility, not all clicks are equal. Today’s online click proposition has risks (you surrender potentially very valuable personal data) and rewards (you get the product or service you want) that are not always in balance.

Lying beneath that link you’re about to click on are data collection and analysis tools such as cookies (both session or persistent), web beacons, pixel tags, log files, JS scripts, IP addresses and geotags, hooks to ad trackers, social media networks and more.

The Google Analytics dashboard includes a Tracking Code menu, where various visitor tracking tools can be incorporated into a webpage.

Each click reveals so much information about our online and mobile browsing habits that researchers can successfully predict consumer online actions at a somewhat disconcerting rate of over 43 per cent accuracy: click probability calculations and the analysis of clickstream data can lead to significant economic profit (if not other advantages) for the provider, and another factor in the risk-reward equation faced by users.

Today’s online click proposition has risks (you surrender potentially very valuable personal data) and rewards (you get the product or service you want) that are not always in balance. Image: Creative Commons Zero – CC0 Max Pixel.

Like a best friend or intimate partner, websites offer up shopping recommendations that seem to know our every want and desire. Powered by past shopping behaviours (and other clicks we have made), the recommendations can have some utility as a result. But the personal – and actionable – profiles behind such recommendations raise questions about data protection: if I click here, what am I revealing about myself, how will that information be used, and by whom? If I do not click, will I miss out on a useful product or service?

Which clicks are most risky, and which are most rewarding? How to tell the difference?

Researchers at École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne, a Swiss technology and engineering centre, say there are ways to browse the Internet without revealing too much about yourself (like through product searches, recommendations and purchase histories) and without having to forgo the convenience of online links and recommendations.

Mahsa Taziki is a member of the EPFL team that has developed an algorithm-based solution to determine in real-time the amount of information revealed by clicking to rate a potential purchase, for example.

EPFL researcher Mahsa Taziki wants to give users maximum control over their privacy and the data they share. Image Credit: EPFL / Alain Herzog

“Eighty per cent of the clicks provide a utility-privacy trade-off for the users,” Taziki explained. “Some clicks are very useful and don’t compromise your privacy, while others are just the opposite. My objective is to compute accurately the utility and privacy effects of the user’s clicks. The users can decide what to click on, and the service providers can also use it to improve the experience of their users.”

(Just knowing how to improve that user experience by analyzing clicks is a big business unto itself: the global clickstream analytics market is expected to grow from $750 million USD this year to more than $1.5 billion by 2022.)

The EPFL algorithm sizes up every potential click a user is confronted with: the amount of data that will be sent is analyzed, the potential effect on privacy is calculated, and then that’s compared with what a user stands to gain from clicking. The results are presented through a colour-coded “click advisor” so the user can decide whether or not the trade-off is worth it, and whether or not to make that next click.

In a way, it’s like a new online game: the user with the best clicking strategy wins! They get the maximum possible privacy, while still getting the best utility from all sources. It’s a challenging game, however: based on analyzed datasets so far, the EPFL researchers say barely six per cent of clicks improve the recommendation utility without loss of privacy, whereas more than 16 per cent of the clicks pose a high privacy risk without any utility gain.

The EPFL team continues to develop the system, which is now patented. Taziki plans to include a browser extension that can immediately warn users when a website is taking too many liberties with their personal information.

“In the end, we want users to be able to enjoy the benefits of online recommendations while maintaining maximum control over their privacy and the data they share,” she said.

Even as development of that app continues, other products are available to give users awareness and control over the data they share.

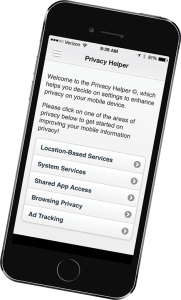

The Privacy Helper app, available in the App Store, gives users information about various privacy options and even uses audio directions to walk them through changing the settings and features on their phones that can affect privacy.

“We call it the privacy paradox,” says France Belanger of the risk-reward proposition that apps like hers are trying to address: “We want to protect ourselves, but we want the goodies.” Phys.org image.

France Belanger, professor of accounting and information systems in the Pamplin College of Business, and Robert Crossler, an assistant professor of information systems at Mississippi State University, design privacy tools that emphasize usability, convenience and personalization, such as the Privacy Helper app.

“We call it the privacy paradox,” says Belanger of the risk-reward proposition that apps like these are trying to address: “We want to protect ourselves, but we want the goodies.”

The Privacy Helper app, available in the App Store, gives users information about various privacy options and even uses audio directions to walk them through changing the settings and features on their phones that can affect privacy.

-30-