Data fuels our economy and helps create some of the richest companies on the planet. Data drives amazing growth across several industrial sectors, particularly social media but also sports and entertainment, health and wellness, retail and marketing, finance and investing and many more.

Yet the creators of that data, us, although often dubbed ‘users’, have been left out of the value statement. You and I and all the people we know who have spent anytime online have not been paid for leaving our valuable data behind.

The tech companies that support all this sharing have long offered their product or service for free, or so it seems. We get a Facebook page, a Twitter account, a YouTube channel or an Instagram feed at no charge.

But what the user provides to the providers is incredibly valuable; it’s called content. There’s enormous potential in this ‘Your Content, Our Profit’ business model, and it’s turned companies like YouTube, Facebook and Twitter into powerful, multi-billion-dollar corporations.

Rather than getting a dividend for sharing, we get taken. Such as when our data is used by parties unknown to develop accurate profiles of our daily social, economic and political activities – profiles that can be used to influence our purchase decisions, shape our economic options or disrupt our voting habits.

Back in 2006, data was dubbed “the new oil”, an accurate nod to its economic impact, fuelling our economy as it were. A sardonic nod perhaps even to the polluting power of data, but not to its natural proclivity to reproduce!

Oil is a finite, non-renewable asset. Data, on the other hand, shows no sign of scarcity: we’re creating more and more of it all the time (see below for the ‘Data Never Sleeps’ usage chart from cloud service provider Domo).

Bit by bit, as it were, we should have greater control over our data, data rights advocates say.

Privacy is a big part of that control, of course, but so too respect. We are property owners, after all: our property is valuable and we deserve respect. Dignity. Even money.

Our data is much more valuable than present-day market evaluations and that big tech is making enormous profits by selling our data without giving us our share. It’s not fair, critics say. Data has value when values are moral.

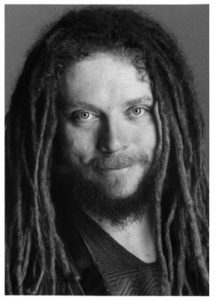

Jaron Lanier, jaronlanier.com

Author, inventor and tech guru Jaron Lanier is one; economist and Microsoft researcher Glen Weyl is another. Together, they have tabled their Data Dignity document, proposing that we must be paid by any company that uses our data.

They’ve estimated that the average family of four could realize some $20,000 for the shared data. Their proposal is three or four years old now; the amount of data we share and its value has only gone up since then.

It is a somewhat complicated model they propose: individuals still must agree to give up usable data to get the services they want from a particular company, then so-called data mediators would have to get the compensation from that firm.

But Data Dignity advocates say it is one way to empower the individual who might otherwise be lost in the overall network effect of the Internet: he or she can gain a kind of democratic bargaining power to counter the big-ness of big tech. Us users can have the ability to make collective decisions about the use of shared data and to negotiate suitable compensation for that use.

A respect for privacy and a payment for data provided does not mean the end of online marketing and user tracking, advocates say, but it does start to paint a picture of an online marketspace that treats the consumer and his or her data with dignity and respect, based on fully informed consent and carefully defined permissions. A U.S.-centric group called the Ethical Tech Project wants to protect online privacy and data safety and build moral standards into technology that gives people greater control of their data.

EthicalTech is bringing together experts and leaders from the private, public and not-for-profit sectors in order to recapture the Internet’s initial promise and allow future generations to interact, co-create, and exist in a digital world with their privacy – and dignity – intact.

Other data advocates and online activists echo the calls for new data governance models for the use, administration and compensation of data collected from individuals as well as the collective data used in machine learning and artificial intelligence product and service development.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation has long advocated for a kind of information fiduciary as a way to bring balance and dignity to the equation. Fiduciaries are based on centuries-old economic imbalances, such as when ordinary people entrust their personal information to highly skilled professionals (doctors or lawyers, for example). Those professionals must act competently and diligently to avoid harm to their customers. Their actions are enforced by government licensing boards and economic penalties against fiduciaries who do wrong. A value judgment is levied.

Big tech, say EFF spokespersons, should have a fiduciary relationship with all of us. There is a direct contractual relationship between customer and company, which collects a great deal of personal information from their customers. The value of that collected information gives the company an unfair advantage: online businesses can monitor – even influence – their customers’ activities, but the customer does not have reciprocal power.

EFF supports legislation to create “information fiduciary” rules, saying that the data collecting company owes fiduciary duties to their customer concerning the use, storage and disclosure of the customer’s personal information. Covered entities would include search engines, ISPs, email providers, cloud storage services, social media platforms and online companies that track user activity online.

Other data rights and data compensation advocates make similar calls, such as Austrian online privacy activist Max Schrems, who has formed a Euro-centric campaign group called NOYB (My Privacy is None Of Your Business), aimed at making it simpler for people to control how companies use their personal information.

Sir Tim Berners Lee. Photo by Paul Clarke, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Former U.S. presidential candidate Andrew Yang has launched the Data Dividend Project (DDP), describing ways he is working to help consumers opt out of uncompensated data sharing.

And the Father of the Internet, web inventor Tim Berners-Lee is calling for “pods” to be added to his creation.

Personal Online Data Stores, or PODS, are a kind of personal data repository and fiduciary in one: Using their PODS, individuals can manage their own data, set their own individual data preferences and gain control or autonomy over the personal data tracking that goes on in public spaces, virtual or physical.

Through his Solid Project, he says PODS represent a small cost to safely control our big data. Our data has even greater value than we suspect: Values are the weights we use in the never-ending balancing act of life. Be they moral groundings or simple price points.

# # #

In its 10th annual “Data Never Sleeps” infographic, cloud service provider Domo looks at the data being created online – the volume and variety of data keeps accelerating, showing no signs of slowing down.