As much as we love all music, we may not realize just how closely this remarkably personal art form is connected to science. To mathematics. Even to animal husbandry.

Yet somehow, music is still enjoyable!

The many points of intersection among music, science, and technology are explored in a great new book aimed at young people, but filled with enough interesting information to keep adults tuned in.

Canadian author, musicologist, and broadcaster Alan Cross, the man behind the radio series “The Ongoing History of New Music”, has now co-authored The Science of Song.

(For example, there is a scientifically researched explanation behind the “earworm”. That song you can’t get out of your head is stuck there for a psychological, even neurological, reason. Too bad there isn’t a scientifically guaranteed method to get rid of it.)

The Science of Song was written and researched by Canadian author, musicologist, and broadcaster Alan Cross, working with two other writers and an illustrator: Emme Cross, Nicole Mortillaro, and Carl Weins.

In conversation with Alan, it becomes clear that the new book is at least partly based on writing and research he did some ten years ago for a travelling museum show called “The Science of Rock ‘n’ Roll.”

Cross recalls that exhibit toured through the U.S. and stopped at the Ontario Science Centre for a six-month engagement. At the stops he was able to attend, he watched with amazement at “the way young people got into the show, and into music history. They were really fascinated by things often taken for granted, the things we need to make or listen or distribute music.”

This 1901 newspaper ad (not in the book) promotes the graphophone, later the phonograph, an early example of technology used to record and play back sound.

Those things could include the first device to record and play back sound, Edison’s phonograph. Or its eventual replacement, known as the 45 RPM or long-playing record. Perhaps the famous “idea that bombed”, otherwise known as the 8-track cartridge. Right on up to the latest and greatest digital devices, exhibit attendees were enthralled by all the musical technology on display.

The energy and enthusiasm were palpable, he described, and that led him to talk to his contacts at Corus Entertainment in Toronto to see what else could be done with the exhibition material. The publishing arm at Corus, KidsCanPress, picked up the tune from there and released the book earlier this year.

Asked about all the points of intersection between music and other disciplines, Cross speaks first to the math: “How did we determine the twelve notes we use in Western music?” he asks rhetorically.

Ugg…math.

Around 500 BC, the Greek philosopher Pythagoras began to study sounds and ratios among lengths of vibrating strings. He codified the fixed relationship between the strings and the frequencies of their corresponding musical notes, higher or lower in pitch.

(‘Papa’ Pythagoras is known as “Father of Music”, also the “Father of Geometry” and the “Father of Mathematics”!)

And while we don’t know for sure why humans became musical in the first place, there is something hard-wired in our brain – places specifically for processing in our brain – for music. “Music may not serve a biological or evolutionary need,” Cross says. “But humans early on may have tried to imitate bird songs.”

Another theory Cross likes says that song, in the form of group chanting or “singing”, came about on the hunt. Multiple hunters’ voices, synchronized, could be an effective way to scare or corral a hunted animal.

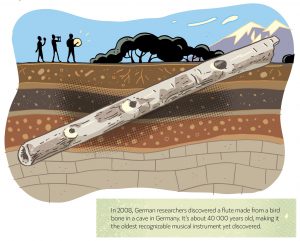

With illustrations and explanations throughout, The Science of Song outlines the history of musical instruments, believed to have started about 40,000 years ago.

Success on the hunt could then lead to chanting or vocalizing to celebrate and commemorate the event.

As food, hunted animals were crucial for our survival, but they may also have been key to musical performance.

In his book, Cross cites the theory that one of the first musical instruments was, in fact, a bone – and archaeologists know that be it human or animal, a hollow bone and a few well-placed holes can become a musical instrument, like a flute. An animal skin, dried and stretched, can become a drum. Animal horns eventually become, well, horns. Don’t ask about bagpipes!

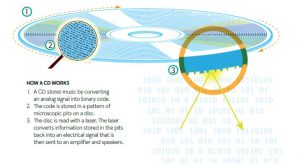

The digitization of music breaks down sound into data, “The Science of Song” explains, and your favourite song becomes a string of zeros and ones that can be easily copied and distributed.

From those ancient origins of music, singing and performance, Cross takes his readers through to more familiar times, discussing as he does the roots of recorded music and the various musical media we’ve used: from the inner mechanics of a cassette tape to an explanation of how a CD works to the birth of streaming media and beyond.

While the book refers to the famous Tupac hologram (a not very sophisticated attempt at demonstrating the future of media), Cross speaks to the upcoming ABBA concert series as a more telling indication of one possible future: a new techno-enabled theatre that can provide “holograms on steroids” is being purpose-built for the hybrid concert series. ABBA is working with George Lucas (of Star Wars fame) and his visual effects company, Industrial Light & Magic, to develop the part virtual, part live experience.

“ABBA has done a lot of motion capture work, and they’re being rendered into super-duper avatars. There will be a live band on stage,” Cross describes, “but ABBA could stay in Stockholm, counting their money.”

His point is well-taken: much of the value in music today lies in the catalogue – particularly when the artist is dead, or too old to perform.

“There is a way to live forever, and the corporeal body can live on,” he laughs. Companies that purchase a song catalogue or own musical copyrights worth millions will need time to get a return on their investment. Special new digital technologies may give them all the time they need.

That’s why Cross is hopeful the travelling science and music show may come back. “I’d love to update it,” he says, “and provide more information for music lovers everywhere.

“The more they know about music, the more enjoyment they can get out of it.”

# # #

Alan Cross, Emme Cross, Nicole Mortillaro and Carl Wiens – a creative team of journalists, writers and illustrators from television, radio and print – have created a fun and informative look at the science behind the art of music.

-30-