Human beings are not the only creatures threatened by infectious disease.

Seems we’re not the only creatures being tracked by technology, either. We share that distinction with, among other critters, ants. However, the ants might not be too concerned about a loss of control over their personal information, freedom or even social privacy.

Ant tracking is a thing, nevertheless. Scientists and researchers are trying to determine how ant colonies hunt for food, even as they (usually successfully) try to reduce risks from deadly pathogens in their midst.

“Automated behavioural tracking” can be used in many research applications. Here, ants are tracked to analyze how they act during a disease outbreak in the colony. Nathalie Stroeymeyt, University of Bristol.

In a science presentation by researcher Nathalie Stroeymeyt, hosted by the University of Bristol, “automated behavioural tracking” is described as a key tool in the analysis of normal ant activities and group communications, even as the insects try to limit the spread of diseases in their colony.

Researchers stuck tiny camera-identifiable markers onto the thorax of multiple ants, so that individual members of the group could be tracked and their behaviours analyzed. Seems ants know enough to self-isolate, by the way; they will adjust their normal activities to remain distanced from others during an infectious outbreak. Scientists tracked ant’s whereabouts and followed their self-quarantine arrangements using tech-enabled tracking tools.

For the rest of us, a coded marker stuck on our back is not necessary. We have our smartphones! And in fact, those mobile devices are being used to watch our habits and activities during the current pandemic. It’s easy.

Just like the small tags affixed to those ants, cellphones and smartphones are easily and uniquely identifiable due to a number of mobile device IDs: they all have what is called an IMEI, an International Mobile Equipment Identity number, with a unique 15-digit tag that specifically identifies a certain device.

But the IMEI number is different from another trackable number: the International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) number, which identifies a subscriber. IMSIs are stored on a phone’s SIM card, which can be pulled from one device and put into another.

Either way, these and other unique identifiers are important to the subscriber’s phone network operator; even if your phone’s ‘location services’ are turned off in individual apps, your phone will still ring when someone calls. No matter where you are on the planet. Identifying numbers in your phone make that happen; the numbers are used to enable basic phone functions and advanced network and security features. They can be used to track and locate your devices in physical space with remarkable accuracy.

GPS sensors, Bluetooth transmitters, and other mobile device functions can also generate location-determining signals accurate to less than a metre, but as you might expect, signal quality often depends on the phone itself, the Wi-Fi transponder or cell tower it is communicating with, even weather and building density or urban build-up in the surrounding area.

But that does not mean those signals are not valuable when trying to tie someone to a particular location and a particular situation.

Say, like storming the U.S. Capitol.

In its remarkable Times Opinion series about smartphone tracking, called One Nation, Tracked, writers at The New York Times shared information they had received about some 100,000 location pings from smartphones in and around the iconic government building in Washington, D.C., on January 6.

Analysts were able to determine that some 40 percent of the phones identified as being near a rally stage while speeches were being made were tracked and later found in and around the Capitol during the siege — a clear link between listening to the speech-makers and marching on the building itself.

Animated graphic renderings of available smartphone location tracking data are used to illustrate tracking efficacy in a series of articles by The New York Times.

In certain animated graphic renderings of available smartphone location tracking data, well, sorry, but the people walking around all look like little ants scurrying around on a big map.

What’s more disconcerting is that such location data is for sale on the open market.

Based on documents reviewed and reported on by The Wall Street Journal, commercial databases with records of the movements of millions of cellphones in America have been purchased by the government for border protection and immigration enforcement purposes.

There are, of course, several commercial sources of accumulated smartphone data, aka predictive analytics and location intelligence. Adobe and Google, not surprisingly, but also companies like Cuebiq, Ubimo, and Mogean.

Some of those sources, some of the companies that are part of what might be called a burgeoning location-tracking industry, are based in Canada. Companies like Hivestock and Pelmorex.

Montreal-based Pelmorex is more widely known to Canadian consumers and weather-watchers as the owner and operator of Canadian specialty channels The Weather Network and MétéoMédia, as well as other international services. Taken together, the weather apps and online services that Pelmorex provides have as many as 46 million global users. Their data habits result in more than a billion location records every month, so as the company says, the sheer volume of usage and behaviour data that passes through Pelmorex’s fingers is massive.

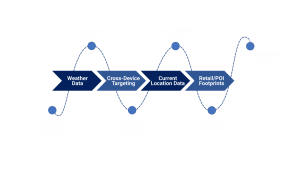

Data from popular weather apps can be accumulated by the Pelmorex Data Solutions division and used to drive marketing strategies and targeting efforts. PDS image.

The data are managed through the Pelmorex Data Solutions division and used to deliver marketing strategies and targeting efforts.

B.C.-based Hivestack says it partners with various data companies in order to understand how a target audience moves around throughout the day. That understanding comes from aggregated anonymous signaling data, accumulated from cellular networks that process more than 15 billion signals a day, and derived from 100 million mobile devices.

Such a massive dataset includes actionable insights about what devices were observed in what places of interest, and it informs the development of unique value propositions based on accumulated and analyzed mobility tracking data, including device IDs obtained directly from mobile exchanges.

So those tracked ants may not think about the data in their lives, especially in the face of a contagious disease in the colony. But they are not the only creatures being tracked.

Analyzing mobility data to inform health actions during a pandemic is for us, too. Several research projects have been conducted or are under way during the current COVID-19 crisis: as we move around, even if under stay-at-home restrictions, our movements can have a really powerful impact on the way transmission occurs and contagion spreads. So public health investigators, using what are called anonymized data, are assessing how mobility affects the spread of the disease among humans. Researchers looked at anonymized smartphone mobility data from March 15, 2020, to March 6, 2021, both nationally and provincially, controlling for date and temperature. They found that a 10% increase in the mobility of Canadians outside their homes correlated with a 25% increase in subsequent SARS-CoV-2 weekly growth rates.

Giving us something to think about in our colony, uhh, lives.

# # #

Nearly ten years ago, WhatsYourTech.ca published a story about how mobile phone tracking was raising privacy concerns. We can see today that was probably not making a mountain out of an anthill. WYT image.

-30-

Bees do it, too.

Word of another study that shows how insects know enough to follow physical distancing and self-quarantine practices during an epidemic.

Researchers noted how “It might behoove skeptics of lockdowns by humans to take note.”

Source: “Honey bees increase social distancing when facing the ectoparasite Varroa destructor”, by M. Pusceddu et al., 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8555907/