Drones are able to fly further distances, carry greater payloads and withstand worse weather conditions than ever before.

The new capabilities in both recreational and industrial drones will bring new rules, regulations and restrictions to the operation of these autonomous or remotely piloted aerial vehicles. Here in Canada, the new rules take effect on June 1. Until that time, the existing rules remain in effect.

But developments in drone technologies and operating software also bring greater ability to provide a range of services to remote communities, in emergency situations and for urban lifestyles.

COMMERCIAL DRONE DEPLOYMENTS

For example, Drone Delivery Canada (DDC) has launched its newest cargo drone, capable of carrying a payload of nearly 200 kilograms (about 400 pounds) as far as 200 kilometres (roughly 125 miles).

DDC calls its big bird the Condor and says it is essential to being able to deliver things like food, medical supplies and bulky items to the country’s remote and Indigenous communities more efficiently and at reduced cost.

Powered by a gas engine (not Li-Ion batteries), the drone can carry either static or tethered cargo under its 20-foot wingspan.

And while even larger-capacity drones are anticipated, DDC, of course, has smaller drones in its fleet, and they have been used to get medical supplies, mail and other parcels up to the James Bay region as part of a $2.5-million commercial agreement with Moose Cree First Nation. Much of DDC’s drone activity is controlled from its Vaughan, ON-based headquarters, where operators work in an air traffic control centre-like facility to monitor and control drone flights.

Out west, an increasing need of companies and educational institutions for testing and trying commercial drones and autonomous aerial vehicles has led Calgary to set aside some 125 acres of open industrial land as a drone testing centre.

The Point Trotter Autonomous Systems Testing Area (ASTA) provides airspace for drone testing and evaluation of potential uses such as capturing geographic and geospatial information for many different sectors, from oil & gas exploration to film & video production. Users of the test centre must have $2 million in corporate liability insurance and a special flight operations certificate for drone technology.

DRONES COVER SECURITY CONCERNS

So product delivery and land surveying are not the only uses for a drone, of course. Governments, military and police services obviously have an interest in using them – and an equal interest in NOT having drones used against them.

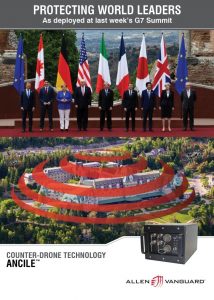

Canadian anti-drone technology is used to protect world leaders and government officials. Company promotional literature.

That’s where the Canadian technology corporation Allen-Vanguard comes in: it used one of its latest products to safeguard world leaders and other attendees at last summer’s G7 Summit in Canada.

Named ANCILE, the product provides a counter-drone capability or “electronic shield” for defeating commercial drones or unmanned aerial systems. Using a kind of RF inhibition system to disrupt the command and control protocols under which most drones operate, the company says its system “ensures total enforcement of no-fly zones to protect convoys, operating bases, sensitive locations and public events.”

“We are proud of our work at the recent G7 Summit and ANCILE’s proven ability to protect and safeguard people and valuable assets,” Mike Dithurbide, President of Allen-Vanguard Electronic Systems, said in a statement released at the time. “Until now there has been no effective counter-measure that is also affordable, portable, easy to use and readily deployable anywhere in the world, including urban environments.”

URBAN AIR MOBILITY AND THE SMART CITY

The urban landscape may be the final frontier for drones. No city has yet really had to deal with large-scale drone deployments – they are coming, however!

When that happens, cities will need to frame the emerging concept of urban air mobility with discussions about technical, legal, social and spatial concerns.

Twittersphere is a whole new kind of social communication space; the dronesphere will be a whole new kind of urban transportation space.

We’re used to the movement of people and things at ground level – but the drone highway or roadway of the future will be much different. The development of new transportation and communication infrastructure, much less civic and public participation in the development of such infrastructures, will be even more crucial in the crowded urban environment.

(Kind of like the Twittersphere, wherein technology has been used to create a whole new kind of social communication space, the dronesphere will be a whole new kind of urban transportation space. Futuristic ideas like these were a big part of the agenda of discussions and demonstrations about drones at a conference held in Toronto last month.)

Whether used for simple recreation, commercial delivery, emergency rescue or military conflict, drones are gaining in capability and functionality. Increased travel distances and carrying capacities, autonomous or beyond-line-of-sight operational abilities mean that drones can handle a range of complex needs that can occur anywhere in the world.

Airobotics, an Israeli start-up that manufactures fully-automated industrial drones, is one of the leading international companies in the sector. It’s the first to receive a US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) certificate allowing Beyond Visual Line of Sight automated drone operations, even if flying over populated areas and even at night.

Airobotics is one of the first drone makers to get permission for Beyond Visual Line of Sight automated drone operations, even if flying over populated areas and even at night. Airobotics image.

The company can, therefore, manage drone activity from its Remote Operations Center in Scottsdale, Arizona as its worldwide operations expand, primarily to serve demanding industrial clients but also its new division dedicated to homeland security and defence.

Interestingly, the company is also directly involved in the future of smart cities: the company sees pilotless drones and industrial grade aerial platforms as a way to provide accurate and frequent data-driven solutions for increasing urban efficiencies while decreasing operational costs.

Think of a pilotless drone as part of the Internet of Things, automatically, remotely, independently capturing massive amounts of data from its unique vantage point high above the city, its people and its patterns.

That’s part of the vision at SNC Lavelin, the Canadian professional services and management company often spoken of for reason other than drone surveillance.

A group of drones approaches a city, perhaps to create a digital version of reality. SNC Lavelin image

But the company’s Reality Capture initiative combines strengths in drone and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) systems, mobile LiDAR (light detection and ranging is a remote sensing and measuring tool using pulsed lasers to calculate distance) and other technologies “to capture, analyze and visualize data …and produce a digital version of … reality.”

Now there’s a development — drones delivering digital reality as well as food.

-30-